Why was Bergen man released from prison decades after murder? Examining the parole process

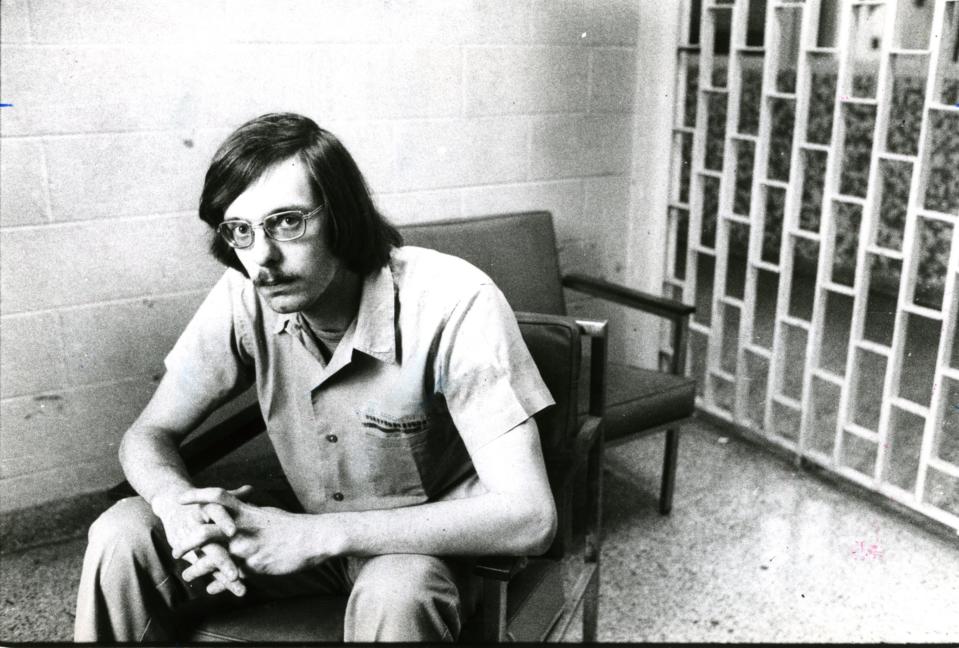

What seems like a lifetime prison sentence in a horrific murder case does not always turn out that way. One example is Harry De La Roche, who spent 45 years in prison for the murder of his family in Montvale before recently being released on parole.

The Bergen County case illustrates the complex nature of parole boards and the process of releasing an inmate years or even decades later.

The New Jersey State Parole Board's straying from guidelines may have played a role in prolonging the incarceration of De La Roche, according to professor Jenny-Brooke Condon at Seton Hall Law and professor Laura Cohen at Rutgers Law.

De La Roche was recently granted parole on his seventh attempt after spending 45 years in prison for the murder of his parents and two brothers.

“This is the right result, it seems,” Condon said. “Given what I've seen about the case … the parole board after six times finally looked at the standard and applied it meaningfully.”

Dina Rogers, the director of the Legal Support Unit of the State Parole Board, did not respond to an email asking about the professors' concerns that the board was not following guidelines. Rogers did, however, explain the parole process in a separate interview

In his last parole hearing, in 2019, the panel of parole board members said De La Roche continued to deny killing his parents and youngest brother and appears "to lack discernable emotion or empathy."

Parole guidelines

To determine an individual’s eligibility for parole, guidelines specify that the parole board should review their plan for living after release and their actions since incarcerated, which include factors like their program participation, disciplinary record and work history, Cohen said.

“It’s a lot of factors that go into the parole decision-making process,” Rogers said.

She said that when inmates commit offenses inside prisons, such as assaulting other inmates, smuggling in goods or setting things on fire, it “does not look favorable” and they’re likely to violate their parole.

Board members look at programs completed successfully during incarceration. Rogers said it doesn’t look good for someone who has done nothing to go before the parole board and also fail to take responsibility.

However, the parole board often does not make decisions solely based on this. In many cases, the board decides eligibility by determining whether the individual was punished enough for the crime. This is not in the parole board’s jurisdiction; instead, the trial and sentencing process is lawfully when this kind of decision-making is used, Condon said. Punitive reasoning likely contributed to De La Roche’s six prior denials of parole.

The parole board is appointed by the governor and approved by the Senate. Members serve six-year terms. They are not required to have relevant experience or training that would prepare them "to exercise their discretion in an appropriate way,” Cohen said.

“These are political appointments. Although the law requires board members to have some training or experience in law, criminal justice or the social sciences, this does not ensure that they are qualified to make accurate or fair assessments," Cohen said.

To determine parole eligibility, a panel of two to three people interviews the incarcerated person. The incarcerated person does not have a right to a lawyer at these hearings, Cohen said. Also taken into account by the parole board are documents the Department of Corrections has provided, a psychological evaluation, a packet supplied by the individual in support of the parole request, letters of context or support from people on the outside, and the individual's plan for living after release.

“At these hearings, the focus of the questioning is too often on the underlying crime, rather than everything the person has done and achieved in the intervening years,” Cohen said. “Often that questioning is aggressive and accusatory, and the board’s decision-making is based on whether members believe the person has paid their dues, rather than on the legal standard.”

Board sometimes denies parole without substantial evidence

For people like De La Roche who were convicted before August 1997, the law dictates that they will be released on parole at the time they first become eligible, Condon said. However, this is not applicable if there is a “substantial likelihood that this person is going to reoffend,” she said.

"The board is nearly always inclined to not release people, even though if they were actually following that standard, there would in many instances that I’ve seen … be good reason for people to be presumably releasable," Condon said.

The board is supposed to consider 24 factors when considering the risk of recidivism, including the commission of an offense while incarcerated, program participation and increased maturity of an inmate during incarceration. However, Cohen said, the parole board often uses an ambiguous standard called “lack of insight” into the crime to justify decisions regarding the risk of recidivism.

“It’s harder to show someone’s going to commit a new crime versus a reasonable expectation of parole conditions,” Rogers said.

Parole is presumptive in New Jersey, and the burden is on the parole board to show there is a substantial likelihood of recidivism or parole violations, depending on the year the crime was committed, Rogers said.

“There's no regulatory definition of lack of insight, but it is something that the board, time and again, cites as a basis for denying parole,” Cohen said.

NJ news Murphy moves to halt new gasoline car sales in NJ by 2035. Can it really happen?

Board imposes long future eligibility terms well above guidelines

Long future eligibility terms set by the parole board likely lengthened De La Roche’s time spent in prison, Condon suggested.

When individuals are denied parole, the law says, the presumptive future eligibility term is 27 months. The board can go above or below this by about nine months, though regulations say the board must justify why this amount of time is necessary for the individual to address the issues for which they were denied parole, Condon said. However, the parole board often gives a 10-year term, which is well above what guidelines suggest.

“Very frequently, the person has served their minimum, has appeared in front of the board, has done everything they’re supposed to do, and they still receive a future eligibility term of 10 years,” Cohen said. "That … is quite different from what our cohort states look like. So, for example, in New York, the longest someone who has been denied parole will go without appearing in front of the parole board again is two years.”

De La Roche was given a 10-year future eligibility term in 2019, though his parole eligibility date was reduced by his earning commutation, work and annual review credits, said David Wolfsgruber, executive director of the State Parole Board.

With the passing of the Earn Your Way Out Act, a number of inmates don’t even need to go before a parole board, qualifying for automatic parole as long as they meet certain parameters. Exclusions include if someone was previously convicted of or is currently serving time under Megan’s Law, the No Early Release Act, the Graves Act or the Sexually Violent Predator Act, Rogers said.

More recent violent offenders, such as those convicted of murder or aggravated manslaughter, are unable to qualify for Earn Your Way Out, as they are subject to serving 85% of their sentence and their parole eligibility is limited, especially in cases of those sentenced to life. The No Early Release Act was passed in 2001. Rogers said the presumed time for life in prison is 75 years, meaning someone must serve 68 years before being eligible.

They would be required to go before the parole board for a hearing, and notifications are sent to people including victims and prosecutors, according to Rogers.

“The board has an influx of cases from the '80s when the Legislature had the 30-year mandatory minimum for murders,” Rogers said. “We’re actually starting to see more of those offenders now become eligible for parole.”

Board weighs factors irrelevant to risk of recidivism

Another factor that may have influenced De La Roche’s denials of parole is that his version of the crime as described in the 2019 hearings does not align with the state’s theory at trial, Condon said. De La Roche claimed in 2019 that he killed only his younger brother, and that his brother killed the rest of his family, whereas the state convicted him of all four murders.

"The parole board denies parole if the person seeking relief deviates at all from the state's version of the case,“ Condon said. "That creates an enormous catch-22 for a person who may actually be innocent, and we know in our criminal justice system there are many people who are innocent who are incarcerated."

The 2019 parole board ruling described De La Roche as "a troubled individual who is unable to adequately delve into his actions and decisions in an honest and forthright manner."

According to Condon, in the 2022 case Berta v. New Jersey State Parole Board, the New Jersey Superior Court Appellate Division found that denying parole because of inconsistencies between Berta's depiction of the crime and the state's theory at trial is "illegal" and "not a basis for saying he's likely to reoffend or that he hasn't been rehabilitated."

Courts push back

Other parole board decisions have also been questioned by New Jersey courts.

The court's increased identification of injustices in the parole system may have played a role in De La Roche’s sudden release from prison, Condon said. For example, in 2022, the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed a denial of parole for 85-year-old Sundiata Acoli, who murdered a state trooper and injured another in 1973.

Acoli was initially denied parole on the grounds that there was a substantial likelihood he would commit a crime if released. The court found that there was no substantial evidence of this and overturned the decision, Condon said.

However, she does not believe that increased scrutiny by the courts will be enough to change the parole board’s decision-making across all cases.

“From my vantage point, it looks like in cases of people who are senior citizens who have been denied multiple times, and where there is a very strong argument about the age-crime curve … the parole board might be more cognizant of fulfilling their duty to act rationally and follow the law,” Condon said. “In the wide range of other cases, I think the kind of lawlessness that I've described is probably going to continue … these issues … they're by no means solved by some of the recent favorable decisions by the court.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Harry De La Roche murder case an example of parole process