Why you get campaign texts calling you the wrong name

American voters are getting inundated with texts from political campaigns asking them to support their candidate. Many of those texts, however, are filled with errors: they address the recipient by the wrong name, assume they live in a different state, or mix up party affiliations. People get mistaken for their parents or complete strangers. Sometimes the results are comical.

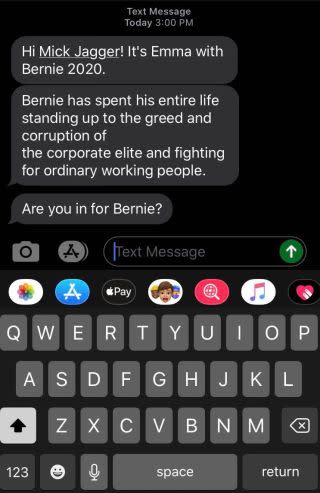

An editor at Quartz gets texts from the Bernie Sanders campaign addressing her as Mick Jagger—a name she jokingly gave to several subscription services and assigns herself in friends’ contacts.

I just got my 3rd text from the Beto campaign to the WRONG PERSON. My friends are getting “Beto spammed”, too. Go early vote – and not for someone who views you as just a random name/number! I’m not Anthony, Cynthia, or Emma. I’m Jackie, and I’m voting for @tedcruz.

— Jackie C. (@Fair_and_Biased) October 22, 2018

There are several reasons for all the confusion, political consultants and experts have told Quartz. First, there’s the simple matter of scale. There are more texts going out in political campaigns than ever before.

“Even if they’re 90% right, if you’re sending a million messages, 100,000 are going to the wrong people,” said Brannon Miller, a political consultant with Chism Strategies.

Whether the campaign is getting a voter’s name right depends on the quality of its data. “When data is gathered directly from voters—say from campaign rallies, donation forms, etc.—is cleaner,” said in an email Daniel Kriess, a political communications professor at the University of North Carolina and author of “Prototype Politics,” a book about tech in political campaigns. But contact lists come from many sources—and definitely not just those that you opt-in to.

I gave to @BetoORourke's 2018 senate run. I received texts calling me the wrong name to help w/Beto's campaign. Just now, I got a text from the Yang campaign calling me that wrong name. I've never given any info to the Yang campaign. Not cool!!

— Nan From CT (@womenstrongnow) November 8, 2019

How is it that every time Bernie's campaign texts me it's with a different wrong name and a state I haven't lived in for years pic.twitter.com/O2rqcotAnj

— Clarissa Young (@clarissa_y) January 30, 2020

Some information comes from voter files, commercial databases that gather publicly available information such as voter registration records. Sometimes phone numbers are a part of a voter’s registration, other times voter-file companies get the digits from phone companies themselves—which can lead to guessing which phone number goes with which family member sharing a plan, said Miller.

Other data comes from third-party databases in a process that is “not dissimilar” to how the marketing world gets information on consumers, said Elizabeth Haynes, founder of TextOut, a campaign texting tool. This is presumably how the “Mick Jagger” texts happened.

Data points campaigns collect are triangulated, to achieve accuracy, according to Haynes. The better the databases, and the more of them you have, the better the chances of a precise match.

“Those data sets are expensive,” Haynes added.

“Part of the problem is all these people have collected all this information without real opt-in, and are going around selling it, and it’s not being properly vetted,” said Jeff Chester, who directs the Center for Digital Democracy.

Some companies that sell voter data do vet it and assign scores based on their confidence that the phone number and the person match. A campaign might target only those contacts with high confidence scores, or it might treat a text blast more like a flyer, casting a wide net, Haynes said.

I also got a text from Bernies campaign. It was my number, but wrong name. I also answered back that I would NEVER vote for a socialist. They replied that they were sorry to have mistakenly sent that text, and said they’d remove my number

— @f09047075 (@f09047075) January 13, 2020

In the Democratic primary race, the campaigns often use the same basic database from the Democratic National Committee. But there are data firewalls between the campaigns, so even if a voter corrects their name with one campaign, the others won’t see that correction.

Because I went to college in NH, I get hit up every election cycle from campaigns for voting in NH. So far I've gotten texts from:

– @AndrewYang

– @ewarren

– @BernieSanders

– @TomSteyerAll have gotten my name wrong, but Steyer's campaign actually apologized when I responded.

— Brenaldo (@SaintBrendan) January 30, 2020

People think that there is an “imaginary database in the sky that we’re all pulling data from,” said Haynes. “That’s just not how it works”

Sorry, Mick.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz:

India may have only three confirmed cases of coronavirus but Indians aren’t taking any chances

Here’s more proof that Trump’s H-1B crackdown is only helping Canada