Why the children of Claxton, Tennessee, have a playground built on top of coal ash

In the hills of East Tennessee, just a half hour outside Knoxville, is a wood-framed playground that looks like a palace for children. It’s just over 20 years old, designed by kids and built by a community that wanted to create a place where its children could play for years to come. And it sits in the shadow of a tall coal smokestack that was constructed in the 1960s.

Welcome to Claxton, Tennessee, where coal ash used to fall from the sky and a playground was built on top of it.

Coal ash is the concentrated waste left over after burning coal. It can contain heavy metals and potentially elements that emit radiation, each posing its own level of health concerns. “Coal ash contains contaminants like mercury, cadmium, chromium and arsenic associated with cancer and various other serious health effects,” the Environmental Protection Agency said in a 2023 news release.

When the Tennessee Valley Authority started up Claxton's coal-fired Bull Run Fossil Plant in 1967, it was the largest generator by volume of steam in the world. It didn’t have scrubber technology on the original 800-foot-tall smokestack, so ash used to fall across the community.

TVA went so far as to build a car wash in the mid-1970s so locals could clean off their dusty vehicles. Back then, there wasn’t widespread knowledge about what was in the ash and whether it was safe to be around.

“I remember when the car wash was going, when the ash really did fall all over Claxton. When you got up in the morning, and there was a quarter inch of ash on your vehicle every morning,” said David Bunch, a former resident of Claxton who now lives about 15 minutes away from Bull Run. “I mean, all over everything; picnic tables had to be wiped off. I mean, it would be thick on there. But nobody cared.”

Kingston opened eyes to coal ash health risks

Times have changed, especially after TVA’s Kingston coal ash spill occurred just 30 minutes away from Claxton. On Dec. 22, 2008, a dike holding back a slurry of coal ash at TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant broke, releasing 5.4 million cubic yards of ash that spilled into the Emory River Channel and swamped entire homes.

Five years after the Kingston spill, the workers who cleaned up the ash began filing lawsuits against TVA’s contractor, Jacobs Solutions, which was in charge of sitewide safety and health. The workers won the first phase of a two-part trial with a jury determining 10 of their health conditions and diseases could be linked to the workers’ exposure to the ash on the site and Jacobs’ negligence in protecting them from it. The workers reached a settlement with Jacobs in May 2023.

“I think events at Kingston, some of the lawsuits, those issues have raised the discussion about ash and what is it,” Anderson County Mayor Terry Frank said.

Millions of tons of coal ash result from decades of burning coal

Coal ash can be found just about anywhere. The United States has been burning coal for more than a century, creating millions of tons of waste over the years, but only in the past decade has the process been regarded as an environmental and public health concern.

Some of the ash was disposed of in landfills, some of it was reused in concrete and some of it was used as fill to level land, which happened at the Claxton playground site. We don’t know where it all is or exactly what dangers it poses to the communities near such sites.

Regulations at the state and federal level don’t fully cover all the places and ways coal ash has been disposed of or reused, and they also don’t always account for the long-term future safety for communities near those sites, said Lisa Evans, an attorney who specializes in hazardous waste law at the environmental advocacy group EarthJustice.

“There's not an easy fix; there's not going to be a cheap fix," Anderson County Commission Chair Josh Anderson said. "And it’s a complicated thing … I'm not saying we're stuck with it, but you can't just close the door and say, ‘OK, we're walking away.'"

How Claxton became an ‘energy community’

About 20 years before the Claxton playground was built in 2000, David Bunch was a child running around Claxton with his friends.

Today, if you look at the land around the playground, you will see a couple of grass-covered hills of coal fly ash (a powdery form of coal ash), one partially uncovered hill of coal fly ash and a coal pile next door.

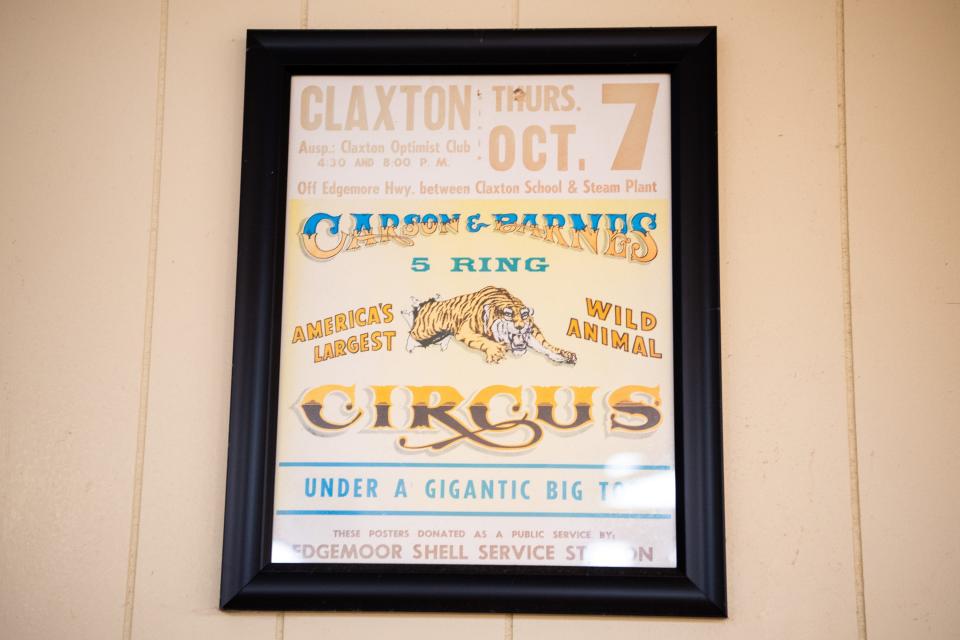

Before the land behind the playground was used to store coal ash, it was open to the community. Bunch would attend jamborees and fairs there, laughing and teasing his friends.

The area was shaped by the federal government: TVA's coal plant in Claxton, the Department of Energy at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, the Y-12 National Security Complex in Anderson County and government contractors running the facilities and creating the next generation of energy technology for the country.

“To me it's almost everybody's got a story in their own personal history that kind of ties to it (TVA) or ties in with it,” Anderson said. “It's either in ‘Grandpa's farm was taken by the TVA to build this,’ ‘Grandpa helped build this,’ ‘Grandpa worked there for 30 years,’ ‘I worked there for 30 years,’ whatever. … Everyone's kind of grown up, like, literally within the shadow of the smokestack and their whole history is kind of centered around it.”

With those facilities came jobs and economic development for communities around East Tennessee.

“We came from those plants; we came from TVA building that steam plant there,” Bunch said. “That’s the reason people came to that little part of the world, to make a family, and they are still coming.”

Bunch remembers when the dream was to grow up and work at the plants, where the pay was good.

Federal agencies like TVA and the Department of Energy and federal contractors were a major part of the economy in East Tennessee and communities like Claxton. Those communities, in turn, provided TVA with land and a workforce.

It was that give-and-take relationship between the community and its federal neighbors that ultimately led to construction of the playground.

Teaming up to provide Claxton's kids with a playground

In 2000, the kids were the center of the Claxton community. Parents got to know one another through their kids, but there wasn’t a whole lot in Claxton to nurture the community environment for families.

“Prior to the playground, there was just some very bare softball fields, and … there wasn't anything there except these fields that TVA laid out for us, and then they were able to help us with this park,” said Tracy Wandell, one of Anderson County’s commissioners for the Claxton district.

Kathy Causseaux grew up in Claxton and moved to Florida but would bring her kids back to see their grandparents. When they visited, her parents always took the kids to a park in Oak Ridge that was built by a company called Leathers & Associates. The park was so popular with her kids, Causseaux and her husband decided they needed one like it back home in Florida.

“My mother came down to babysit while me and my husband worked. My husband was the foreman of this playground we built in Florida,” Causseaux said. “And my dad came down and worked for a solid week on that playground. And when we finished he was like ‘I want one of these in Claxton. We can do this.’”

Sure enough, Causseaux’s father started wrangling support within the community to build Claxton a playground. Government contractors Bechtel Jacobs, Lockheed Martin and UT-Battelle donated $67,500 to the Claxton Optimist Club to help establish the playground.

Meanwhile, TVA donated land on the edge of the Bull Run plant’s property for the playground. But the land needed to be leveled.

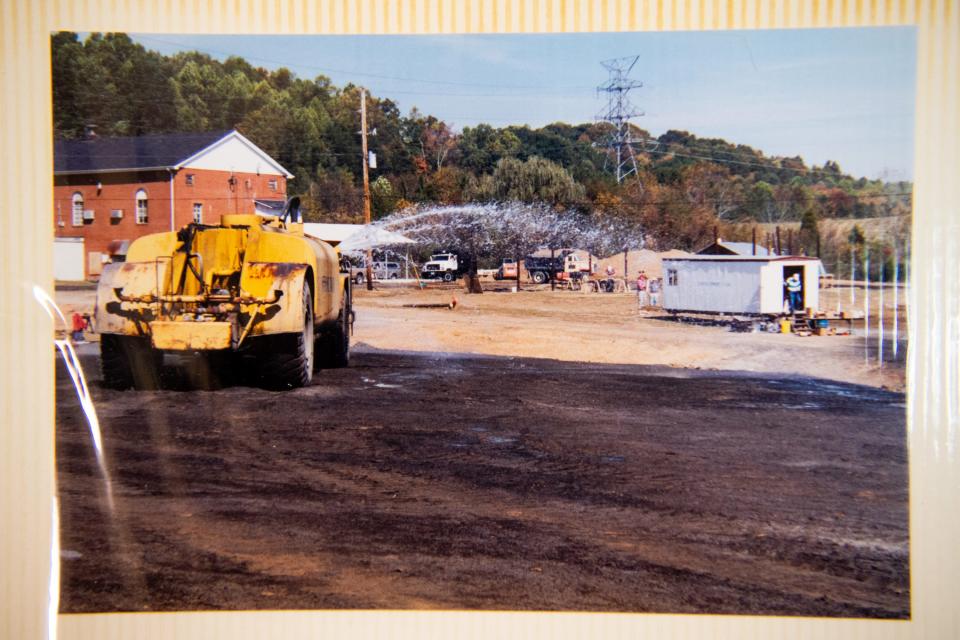

“As part of the project, TVA prepared the site and provided fill materials, mainly comprised of soil but which also included a small portion of bottom ash, while the Claxton Optimist Club provided the remaining materials, including multiple layers of geofibers, gravel and mulch on top,” TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks told Knox News, part of the USA TODAY Network, in an email.

Brooks said the project required 11,000 cubic yards of fill material, about 30% of which was coal bottom ash. That's about 3,300 cubic yards of coal bottom ash that needed to be watered and packed down before the community came in to build on top of it.

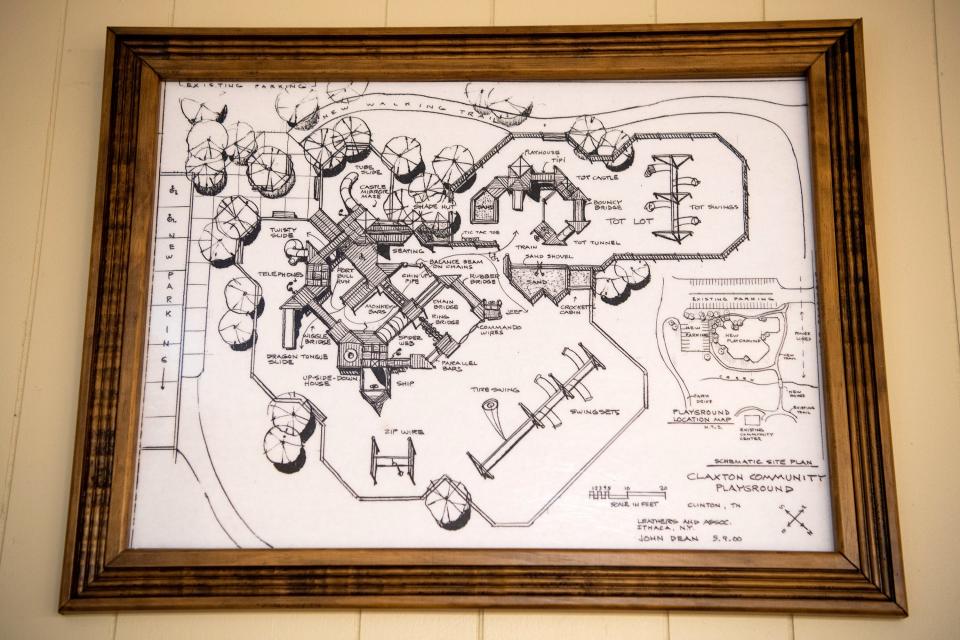

In the meantime, the Leathers & Associates playground company sent a designer who spoke to the kids at Claxton Elementary School, just down the road from the Bull Run plant. The kids not only shared their ideas for what they wanted, they also decided on the playground’s name: Kid’s Palace.

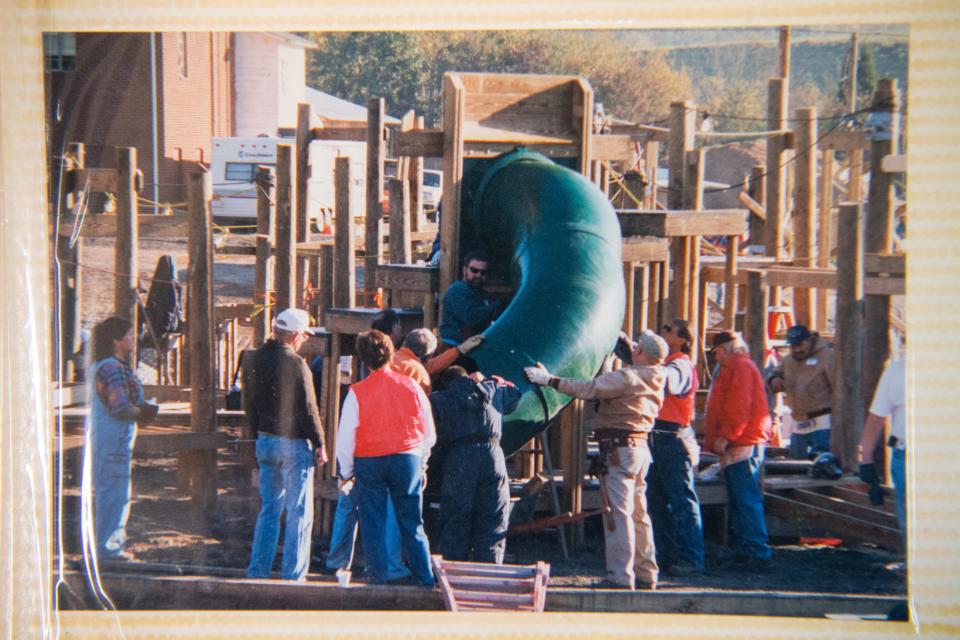

The community then spent a whole week building it.

“You feed your people two to three meals a day and they work for seven solid days and on the last day you have a grand opening and all the kids come and get to play on the playground,” Causseaux said.

About 23 years later, the Claxton playground still stands.

Coal ash science is developing, but it can be hard to assess risks

When Denise Hodgson moved out to Anderson County, away from the traffic jams of West Knoxville, she was looking for more open space where her kids to play.

All of her kids have asthma, and when she moved to live near Bull Run, Hodgson said her pulmonologist increased monitoring of the kids. With her youngest in a wheelchair and the Claxton playground inaccessible for kids with physical challenges, Hodgson said she couldn’t take her child to the playground.

But even if she could she wouldn’t - the risk of the ash under and around the playground was too high.

Fly ash has a consistency similar to a powder, while bottom ash is coarser, like sand and gravel. This is important, because as these wastes are created, they contain concentrated elements such as heavy metals and potentially elements that emit radiation.

The smaller the particle, the more concentrated the elements on it. The particles themselves can cause health problems. Add in the different elements such as arsenic, lead and mercury, and each can pose its own potential health problem. The smaller the particle, the easier it is to inhale or ingest and potentially to go deeper into the body.

While the experience of the Kingston coal ash workers brought to light some of the worst health impacts coal ash can have on the body, research still is being done to understand what small amounts of exposure to the ash can do over different periods of time. The impact the ash could have on kids could differ from its effect on adults or people with preexisting conditions.

Studying and regulating the use or disposal of coal ash is complicated by the fact that every batch of coal ash is different depending on where the coal came from and how it was processed and burned.

With these uncertainties about the exact dangers of this waste, weighing the risks it carries can be hard, especially for a community that grew up around coal ash.

A few years ago, Bunch probably would have denied there might be any health concerns over the fly ash, he said.

“Well, now I’m a little older and I got a little better sense, I realize it is (a concern). So it just makes me ashamed to keep taking the kids down there. And I mean, that’s on me but still, if it’s bad enough that I don’t need to have my kids down there, my community should be the one telling (me) is it safe or not,” Bunch said.

The state conducted a study but other experts want more information

As the community learned about the potential health risks of coal ash over the years, Anderson County government - which now controls the Kid's Palace property through a long-term easement agreement with TVA - reached out to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation to conduct testing at the playground to ensure its safety.

TDEC collected soil samples that were tested for elements the department associates specifically with identifying coal ash, such as arsenic, lead and mercury.

The state found that two samples taken from under the swings - where the playground’s geofiber layers were worn through, leaving the ground underneath exposed - contained 6% and 9% coal ash. TDEC also consulted the state health department, and the two agencies provided a report in 2022.

The report said the county would need to repair those areas and then institute a maintenance plan to ensure there were adequate levels of mulch, the fabric was not torn and the layers between the surface of the soil and underneath were maintained so coal ash didn’t continue to come up.

Once those precautions were taken, the state said, the playground was safe to use.

“I should be able to trust that they put it (the playground) there (so) it’s safe for us to be on,” Bunch said. “Not, ‘They put it on there and it’s only safe if they put that … landscaping membrane over it. Now it’s safe,’ but if that little membrane tears, it ain’t safe anymore. See, that’s my concern.”

Bunch isn’t the only one concerned. Knox News provided the state’s report to seven experts who have researched and previously looked at coal ash risks, and they each pointed out potential problems with the playground’s current and future safety.

All seven experts raised potential concerns about the coal ash underneath the playground, and also the nearby fly ash disposal site and coal pile and the potential for wind to carry dust from the two adjacent locations.

TVA employs dust suppression systems and compacts the coal ash at its coal plants, but TDEC did not conduct any air monitoring at the playground.

Given the age of the playground and the potential for coal ash exposure from the air and the soil, all seven experts said that, given the uncertainties and variables, moving the playground might be the best option to be absolutely safe.

Nevertheless, some of the experts acknowledged the importance of kids having access to a playground, and if the playground stayed where it is, the majority of the experts said the county should continue to keep its own maintenance plan.

One expert suggested the ash could be removed from underneath the playground, or that signs could be posted to let parents know.

Two suggested the ground could be capped so there’s even more of a barrier between the ash and the surface of the soil where it could come into contact with the kids.

Three of the experts suggested there should be continuous testing to ensure that not only is the playground safe today, but it remains so in the years to come.

At least five of the experts agreed with the state and said that the county should continue to keep a maintenance plan.

As it is now, six of the experts said they as parents would want more information before they would take their own kids to the Claxton playground. One said they would not take their child there.

“The kids and younger age children, they're the most vulnerable in terms of various environmental health impacts, because all their systems they're just developing,” said Dr. Julia Kravchenko, an assistant professor in the department of surgery at Duke University School of Medicine and one of the experts Knox News consulted. “That's why we should be absolutely sure that everything where kids are involved, all areas where they play, what they’re eating, everything is as clean from toxic substances as possible.”

Reused coal ash can be anywhere, and no one knows where it all is

Regulators do not necessarily know the locations where coal ash has been reused like it was at the Claxton playground. Here’s why:

The United States has been burning coal for more than a century, creating millions of tons of waste to be disposed of or reused.

The EPA created the first regulations for disposal of coal ash in 2015, which defined the difference between what is considered disposal versus reuse.

However, the criteria for beneficial use does not apply to legacy sites like the Claxton playground, where coal ash was reused prior to October 2015.

Despite creating the definition, the EPA does not track sites where coal ash is reused.

Without much federal oversight, states are left to create their own regulations for reusing coal ash if they choose to.

And even with states that do have rules specific to coal ash reuse, some acknowledge the possibility they don’t know all of the sites where coal ash was reused predating their regulations.

“So there's a lot more sites presumably out there that we don't have any information on, or if we know about the site there may not have ever been any sampling of ground, surface water or air,” said Lisa Hallowell, an attorney for the Environmental Integrity Project. “So we just don't know how polluted or how much of a problem they are. Because nobody has been required to do the testing.”

EPA is considering expanding its coal ash rule to more sites

The EPA has proposed an expansion to its coal ash rule this year to include more coal ash disposal sites.

When asked about the proposed rule, the EPA said it “would apply only to CCR (coal ash) placed on the land at utility facilities.” In the case of the Claxton playground, the property is owned by TVA, which is a utility corporation, and the land is adjacent to the Bull Run power plant property.

However, the EPA told Knox News, “With the facts we have it appears that the CCR (coal ash) at this site would not be regulated.”

Nevertheless, Evans, the EarthJustice attorney, said it might be possible the proposed rule could apply, especially because the rule has not been finalized.

States are left to try to regulate whether and how to reuse coal ash

State environmental departments are left with the burden of trying to regulate sites like the Claxton playground that were created prior to the federal regulations in 2015.

For example, Montana, Virginia and West Virginia do not allow coal ash to be reused as fill.

In North Carolina, coal ash is permitted to be reused as fill. Similarly, Ohio allows for waste material such as coal ash to be used on land as fill, but the Ohio EPA told Knox News it assesses such use on a case-by-case basis.

Plus there's still the possibility sites where coal ash was reused as fill could have been created prior to a state creating its own regulations.

Officials in Virginia, West Virginia and North Carolina acknowledged the possibility state officials aren't aware of times coal ash was used in fill materials, such as being mixed with fill dirt.

“There were few rules or records regarding the use of coal ash as fill prior to 1987,” North Carolina’s Department of Environment and Quality told Knox News in an email. “Coal ash used as structural fill was not required to be reported to the state environmental agency until 1994.”

A sampling of sites where states know coal ash has been reused include:

Battlefield Golf Club at Centerville in Virginia.

Ball fields that were constructed on top of closed coal ash lagoons in 1996 in Ohio.

Across parts of the town of Pines, Indiana as landscaping fill including in a city park.

Duke University West Campus in Durham, North Carolina.

Englewood Baptist Church in Rocky Mount, North Carolina.

A Family Dollar store in Weldon, North Carolina.

Playground slipped through the cracks in past state regulation of coal ash sites

The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation created a permit by rule program in 1991 for sites that wanted to use coal ash as unencapsulated fill material. The program created regulations such as attaching information about the ash to the deed of the property, and it required barriers to be in place so the ash did not come into contact with groundwater or the surface, to protect communities from environmental releases.

The state's permit program was repealed in 2019 because it did not match the new federal criteria for coal ash reuse established in 2015. TDEC still allows coal ash to be used as fill under a different rule. The state told Knox News it has not seen any specific applications for coal ash fill since 2019.

While TDEC has kept records of sites that fell under its previous permit by rule program from 1991 to 2019, the Claxton playground is not in TDEC’s permit by rule records.

After some emails between TDEC and TVA, it was determined that TVA has contracts with third parties to provide coal ash for reuse as fill.

At the time the Claxton playground was built, the party receiving the ash from TVA would have had the responsibility to obtain the appropriate permissions from TDEC, Brooks said. In the case of the Claxton playground, that appears not to have happened.

One of the community coordinators for the playground told Knox News that TVA brought the ash to the site for fill but the community did not know and was not told it needed a permit.

Today, that means TDEC does not have regulatory authority over the playground.

“TDEC is not the property owner of the playground nor does the agency have regulatory authority over the site. I suggest contacting the county regarding any planning moving forward,” TDEC told Knox News in an email.

This not only leaves the Anderson County government with the burden of deciding the fate of the Claxton playground, but also with the pressure of mitigating health, safety and financial risks to the community as well.

“It puts a pretty heavy burden on those who want to think about it,” former Anderson County Commissioner Catherine Denenberg said.

Claxton residents say they need their playground

With increasing scrutiny of coal ash and its potential health risks, community members fear Claxton might lose the playground even though it can’t afford to.

“I think it's important for kids to have something like that to be able to go out and just get away from all the issues and problems of the world, so-called just be a kid, enjoy themselves,” Commissioner Tracy Wandell said.

More: Climate change warning signs started in the 1800s. Here's what humanity knew and when.

“I remember playing at a playground in Portsmouth, Virginia, in Navy housing, that meant the world to me. It just had maybe three or four swing sets and a merry-go-round. And that's where I would go to get away from everything and just … be a kid,” Wandell said.

Even so, the Claxton community deserves a playground that doesn’t pose a potential risk to the kids’ health, Hodgson said.

Both Frank, the county mayor, and Wandell have said the closure might provide an opportunity for TVA to help the community by moving the playground.

“So, to me, I think the (Bull Run) closure represents a great opportunity to address the reality, which is there is a perception of risk,” Frank said. “I think it's just an opportunity to move it (the playground) somewhere else.”

As TVA continues to evaluate its plans for the plant’s property and the other pieces of land it owns in Claxton, Wandell hopes TVA would be open to helping the community with a new playground - and potentially could help with other public facilities, such as a Emergency Management System building, a new community center, a new volunteer fire department hall and a new Claxton Elementary School building.

“We are working with local officials, including Commissioner Wandell, on options for the future of the Bull Run site - and how we can help meet community needs in general. This is an ongoing conversation,” Brooks said in an email to Knox News.

Aside from the issue of the playground's safety and location, TVA needs to address its plans for the coal ash on its property, whether it's the ash in a dry landfill or underneath the Claxton playground.

To Wandell, the best scenario for the future is a new playground in a new location in Claxton. “So I feel like TVA recognizes they're always going to be the owner of the byproduct that's from the production of electricity, and it's their commitment and obligation in perpetuity to do so," he said. "And I think they understand that and I think that's an obligation they'll have to maintain well after I'm dead and gone.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Claxton, Tennessee, playground was built on top of coal ash