Why the CIA Director Is Declassifying Material on Russia’s Ukraine Plot

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

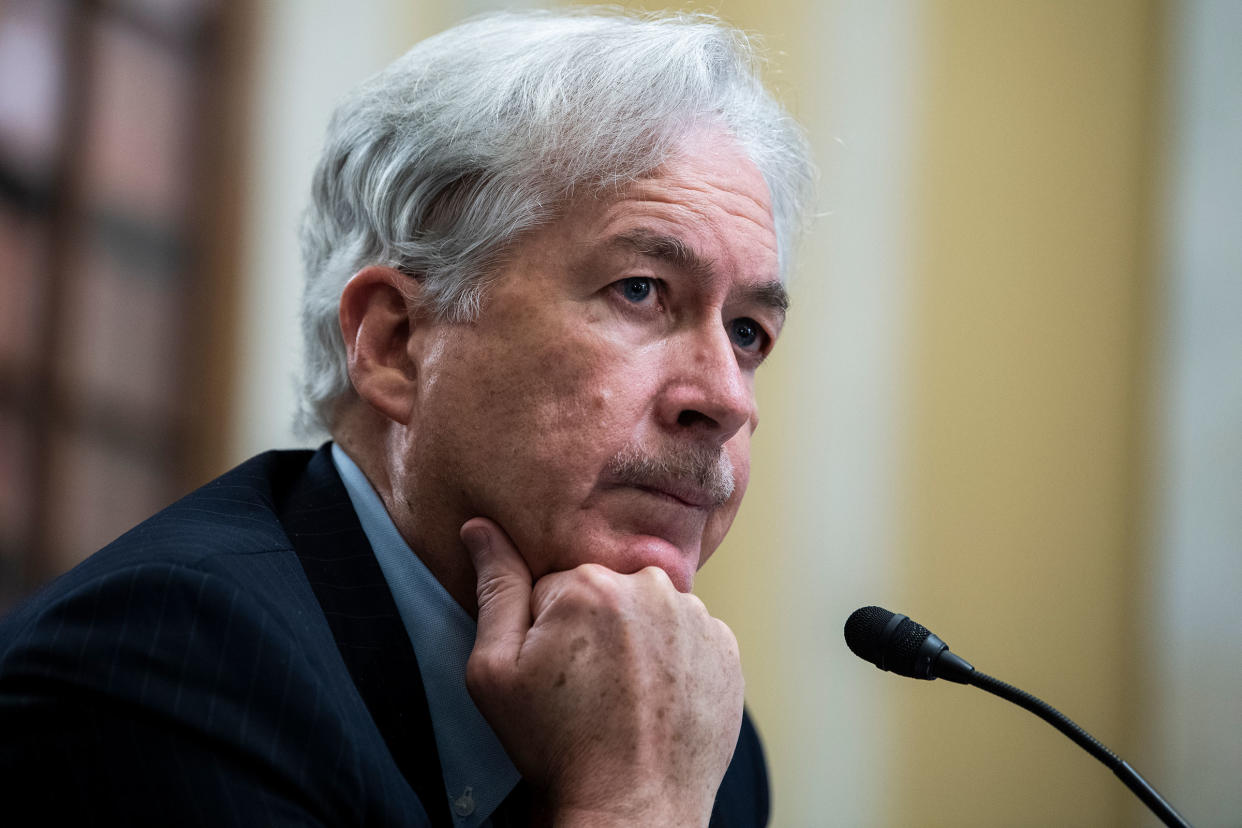

William Burns testifies during his Senate Select Intelligence Committee confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, on Feb. 24, 2021. Credit - Tom Williams—CQ-Roll Call/Getty Images

This article is part of the The DC Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

An ignorance of history isn’t an excuse for bad analysis—especially when your own spies have the evidence on their desks. And few in government understand the perils of a blindspot better than CIA Director William J. Burns.

That’s why in recent weeks, U.S. intelligence officials have moved to quickly declassify what they have said is a Russian plan to spread disinformation about a purported Ukrainian attack on Russian soil. Such a move by Kyiv would precipitate Moscow’s retaliation that wouldn’t stop at borders and instead roll into the Ukrainian capital. In other words, it’s a false-flag operation that could spark the biggest land war in Europe since the 1940s. Put simply: don’t believe everything you read.

The declassification work has been one of the most aggressive moves from the Intelligence Community (I.C.) to reveal the calculation of tricky diplomatic and national security problems since the Kennedy Administration opened their notebooks about the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The I.C. wants the world to know that Washington has the receipts in Kyiv and Moscow should go home—just like the Kremlin retreated from Havana back when Ray Charles topped the charts in 1962.

That is, of course, assuming D.C. isn’t leaning too far over its skis.

The comparison to past transparency-as-strategy operations raises the hackles of folks like Thomas Rid, a Professor of Strategic Studies at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. (What I like to call: Only the Paranoid Survive, Inc.) Google Maps is already providing imagery that in the past would have been available only to U2 spy planes. And in an era of social media, anyone with a smartphone is an amateur foreign correspondent.

“They are declassifying information, no question about it. But they’re adding details to a bigger picture that is already out there,” says Rid, whose 2020 book Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare should be mandatory reading for Washington these days. “The fact that we’ve seen such aggressive declassification by this Administration and by the Intelligence Community in the context of the Russia buildup may be a sign that we here in Washington are overestimating the power of disinformation because of 2016 and then 2020. We may ascribe too much power to disinformation. So as a result, over-declassifying and live-tweeting the Russian intelligence feed, figuratively speaking, reporting their intelligence feed to the public, or at least parts of it, comes at a cost as well. And the cost is that you portray Russia as even more threatening.”

All of this informs Burns’ work. Widely seen as the most polished diplomat of his generation and a favorite student of some of the heavyweights in the profession, Burns helped bring into reality the multinational agreement with Iran to curb its nuclear ambitions and, before that, was the top U.S. diplomat to Moscow. No slouch when it comes to the post-Soviet mindset of the Russians, he’s as skeptical as they come about Moscow’s intentions. In one memo to President George W. Bush and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2008, Burns described Russian President Vladimir Putin as “cocky and combative as ever, still without a mellow bone in his body.”

So as Burns, the Oxford-educated retired diplomat who was confirmed as Biden’s CIA chief last year, looked at the potential battlefield of eastern Europe, he made a play heavily informed by three decades in the State Department’s labyrinths. He and Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines started to share their secrets with the public. The thinking has been that such a public accounting may shame Russia into de-escalating, warn Ukrainians and Russians alike about Moscow’s shady intentions and potentially prime Americans for some level of military engagement. At times, the information has caught Russian officials off guard, unsure of Vladimir Putin’s thinking in a regime where power rests solely in his hands. As a bonus, it’s left Russians worried they have a mole, turning an already insular heir to the KGB paranoid. It’s been an ambitious act of transparency by the U.S., but not one that necessarily has paid tangible dividends so far.

In fact, despite Russia’s claim that it was swerving away from an invasion, NATO and U.S. officials have said they have no evidence that war is less of an option. Ukraine, meanwhile, is considering putting to voters a measure to pledge to eschew NATO membership in a last-minute effort to dodge an invasion. And, in Washington, analysts continue to question whether Putin’s continued talks with the West are a sign of consideration or delay.

History tells us that this should feel familiar. In the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, American officials started to declassify material about Iraq’s ambitions for a weapons program. Ultimately proven incorrect, the I.C. had made a compelling case for U.S. action against the Iraqi regime. And, as it had before during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the American press seemed to have a whole lot of details about what clandestine sources were telling U.S. spies.

“The U.S. intelligence community has improved as a result of a failure. And it’s trying hard not to repeat mistakes,” Rid says. Still, it’s hard not to feel echoes of post-9/11—especially given Burns’ own role as a top State Department bureaucrat overseeing the Middle East at the time.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.