Why is the DA of Sacramento threatening the homeless people at Camp Resolution? | Opinion

Five years ago, Joyce Williams and Sharon Jones were attacked in their south Sacramento rental home in the middle of the night by its owners, who were co-occupants.

“A jealousy thing,” Jones said.

Their belongings thrown onto the front yard, Williams and Jones were escorted off-site by a Sacramento County sheriff’s deputy to a motel off Mack Road. They stayed in one motel after another until they ran out of money. Without a car, their home for more than four years has been somewhere near the American River in Sacramento.

Opinion

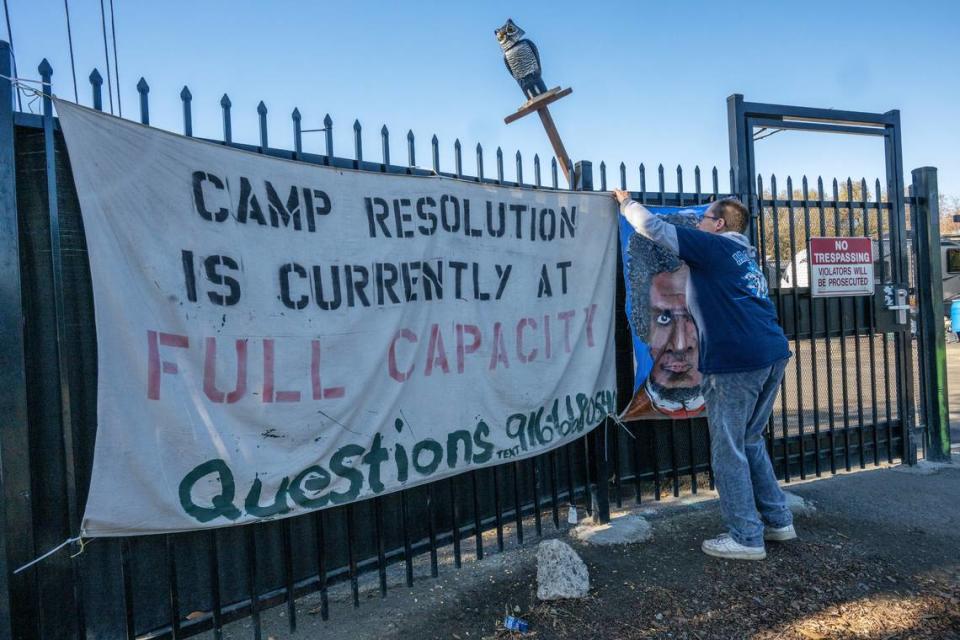

For more than a year, they have led the region’s only self-governing homeless encampment, Camp Resolution, and fought to create it. But now they find themselves fighting a person they have never met, District Attorney Thien Ho.

Ho declared Camp Resolution a “toxic dumpsite” to be abandoned in a letter to Sacramento officials last month. The District Attorney offered no plan on where to move its occupants, most of whom are women. Yet, Ho appears on a trajectory to add Camp Resolution to his September lawsuit against the city.

To Ho, Camp Resolution is yet another “nuisance” that the city has created and that Sacramento County Superior Court Judge Jill Talley must somehow correct.

To Williams and Jones, Camp Resolution is home.

“I think he is using us as a political pawn,” the 55-year-old Jones said. “Why is he messing with us? He should be prosecuting criminals.”

To 55-year-old Williams, Ho’s crusade against Camp Resolution makes no sense. “I thought the county and the city were collaborating for the unhoused people. So why is he going after just the city? Why just the city?”

The two recently discussed their lives and their predicament in the administrative trailer on site. Outside, all the garbage was properly thrown in a trailer. The dogs were on leashes. A friend was leaving a visit with his dog, Nog Nog, in tow. Camp Resolution had every outward semblance of a functioning community. Surrounded by fencing and with a security gate, it is a respite from the dangers of life along the river or on Sacramento’s streets.

Camp Resolution houses 51 people, and it is incredibly cheap for the taxpayer. A non-profit leases the two-acre site from the city for free. In comparison, the city is spending nearly $3.3 million this year at Miller Park in a contract calling for 60 tents and parking for up to 50 clients.

By every measure, Camp Resolution appears to be working. It is so popular, Jones said, that about 800 homeless people are on a waiting list to get in.

More “Safe Ground” sites like Camp Resolution are precisely what it will take to get homeless off the streets and into something far more organized and managed.

“We need immediate relief of the people on the street so the people in the neighborhoods don’t have to worry about the homeless being in their neighborhoods,” Jones said. “Put them in camps or put them in housing.”

Ho’s lawsuit threatens to move Sacramento’s homeless crisis backward, not forward. It is not about finding housing solutions. It is Sacramento County, the designated government provider of social services, that is supposed to be in the lead on that. The county has never been Ho’s target. The fault is always and only with the city. In this instance, he views the former city maintenance yard on Colfax Street in North Sacramento as a contaminated site of toxic chemicals that poses a legal liability to the city.

“It is not compassionate,” Ho wrote, “to purposely expose the unsheltered to poison.”

Sacramento Attorney Mark Merin, who helped craft the Camp Resolution agreement with the city, disputes the charge that the site is unsafe.

“There have been different studies, and one of the studies found the level of benzene is no different than what’s found throughout the state,” he earlier told The Bee.

Meanwhile, Jones and Williams feel perfectly safe at the site. “I don’t know why he is picking on us,” Jones said. “He needs to get his facts straight.”

Ho’s lawsuit has accelerated this couple’s evolution into advocates. The other day, Williams spoke out against Ho at a press conference organized by Sacramento mayor candidate Flo Cofer. Then Jones spoke to an architecture class of about 75 students at Sacramento State, despite her long-held public speaking fear.

The couple’s union years ago was by pure happenstance. Both graduates of local high schools — Jones from Rio Linda, Williams from Burbank — Williams was walking uptown from the Greyhound bus depot one day when she ran into Jones near Henry’s Bar. Both had recognized one another, though they had never spoken.

“I asked her if I could buy her a drink,” Jones said. Williams said yes. “Heck yeah, I did! I was thirsty.”

Together for 23 years and married for 14, Jones and Williams made ends meet for years. With an associate arts degree in data entry, Jones did accounting while Williams was a janitor. They had moved south into the San Joaquin Valley, to Sanger, about seven years ago so Jones could be closer to her family. It was only when they moved back to Sacramento that a rental arrangement devolved into a night of violence and their ultimate displacement.

“I didn’t ask to be homeless,” Jones said. “But I’m here.”

After camping on the lower American River near Steelhead Creek, by 2022 Jones and Williams had moved to the Camp Resolution site. Before that, Williams said, police and rangers had swept the couple from one site or another 11 times in a single month. It was time to fight for a place where law enforcement would leave them alone.

After threats of yet another sweep strategy at Camp Resolution, the city agreed in March to lease the site to the local nonprofit Sacramento Safe Ground. The site’s not perfect. It does not have running water. It is not entirely covered in asphalt. The trailers, which turn into saunas on summer days, have no electricity. But unlike living on the streets, Camp Resolution does have portable restrooms. And security. And occupants who — by all measures — are looking out for one another.

Its existence has created something homeless crave: Stability.

“For a year no one has been swept in this camp,” said Williams. “They haven’t had that stress on them. It’s overwhelming, the preparations for a sweep.”

And now Thien Ho wants to sweep Camp Resolution.

Ho’s warning letter to the city referred to “criminal liability” at Camp Resolution. Ho could have added the encampment to the list of nuisances in his civil lawsuit. Instead, he’s going after the city and the camp’s operators as if the alleged nuisance amounts to a crime. That elevates his attacks against the city to a whole new level.

It’s still early in the procedural process, and Ho remains in attack mode. He has yet to defend anything before a judge in a court of law. Threatening to dismantle this uniquely managed encampment, with no suggested alternative, is a very revealing move for the Sacramento District Attorney. And it’s not a flattering one.

“We’re going to fight back,” said Jones. “We’re going to stand up.”

Her wife agreed.

“We,” said Williams, “are a force to be reckoned with.”