Why did A.B. Farquhar surrender York to the Confederates? He's been unfairly vilified

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

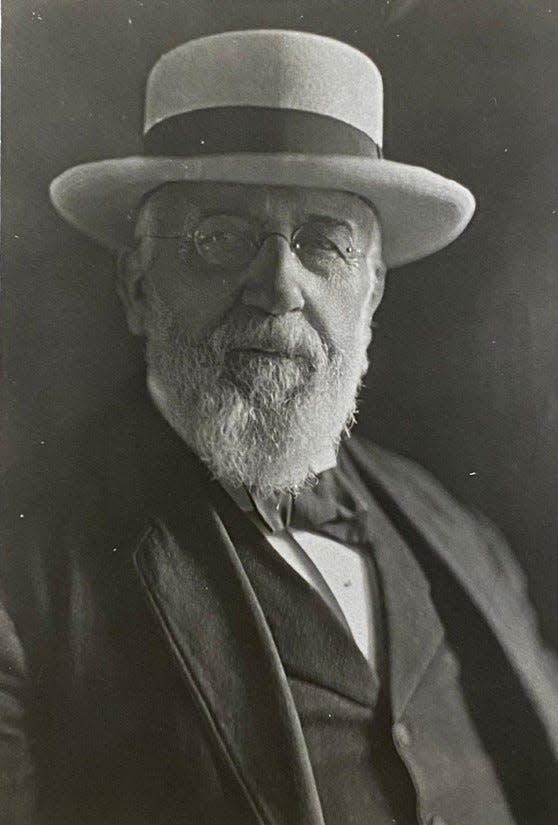

On the 160th anniversary of the June 27, 1863 surrender of York to the approaching Confederate Army, rather than another discussion about the wisdom of the surrender, I believe a portrait of the man who catalyzed this surrender, Arthur Briggs Farquhar, is due.

Over the years the pros and cons of the surrender have been debated by eminent Civil War and local historians such as Scott Mingus and Jim McClure. I am not an historian and cannot offer further historical insights. However, over the last year I have been researching my neighborhood, Farquhar Estates, and have read everything I could find written by and about A. B. Farquhar and I do consider myself to have some expertise in who he was.

It pains me that the contemporary focus on Farquhar’s role in this controversial surrender has overshadowed the numerous personal and civic achievements of this brilliant businessman and highly moral Quaker. This is grossly unfair to him. He was more than this one episode. Farquhar has been characterized as being “impulsive” when he rode out to meet the Confederates and negotiate a surrender to save York from the very real possibility of destruction. Rather than being impulsive I believe he was very deliberate and felt it was his and the town’s only option. He has been described as “laboring to defend his role in the surrender of York” which implies he was ashamed of his actions and even, possibly, that he did not know slavery was wrong. I would assert that he as a staunch Quaker held the same Abolitionist views as did his Quaker family and community. He has stated he was a Union sympathizer, however, apart from his autobiography I could find only one specific statement by Farquhar regarding slavery: In the March 20, 1873 York Daily, in a piece supporting the Temperance movement Farquhar writes, “Through ages gone, the Holy Bible has been invoked to support all manner of villainy—the Crusades, the Inquisition, Human Slavery, and persecutions of every kind:”

By Jim McClure: York’s Civil War surrender at 160: ‘It was not York’s finest moment’

I disagree that in his 1922 autobiography he “labored to defend his role” and believe he included this episode because he was so indignant (his words) and dismayed by those citizens who accused him of being a traitor and of “selling York to the Rebels” that the unjustness of this criticism stayed with him his whole life. Even though Farquhar believed he had done the right thing, these criticisms so affected him that shortly after the surrender he sought out President Lincoln in Washington and asked for his judgement. He managed to meet with Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton where he told his story and asked what they thought. They told him that he deserved a very high commendation and that by his action some millions of dollars’ worth of property had probably been saved at a trifling cost. According to Farquhar’s autobiography Lincoln went on to say, “You were wise not to neglect an opportunity to be of service…The mistake you made was in worrying yourself over what people say about you. You should go through life doing what you believe is right and not bother yourself over what people may say…You can go home and tell them what I have said to you; tell them that you have my thanks and the thanks of the Government.”

Born in 1838 Farquhar was raised in Maryland in a well-off Quaker family holding progressive views advocating education for women and that Black people should be taught to read and write (which was against the law at that time). Farquhar exhibited aptitude for machinery at an early age and after his schooling in Richmond, Virginia, alongside the son of Robert E. Lee, he was assisted by family friends in York, the Jessops, in obtaining a four-year apprenticeship at the W.W. Dingee machine shop. Here he worked alongside woodworkers, machinists and draftsmen to learn the trade while going to business school at night to learn bookkeeping and writing. Within 18 months he felt he was ready to go out on his own and start a company and told his employers he would be leaving. They offered him a partnership instead, and at age 20 he bought into the company with the assistance of a small loan from his father.

In 1860 at age 22 he married Elizabeth Jessop, with whom he had fallen in love when he first met her at 18. They lived in rented rooms near the shop and had their first child in March 1862. The Dingee Machine Shop and A.B. Farquhar were doing well, however, in November of 1862 disaster struck and the Dingee plant burned to the ground. The business was ruined and because it was uninsured they could pay their creditors only 25% of what was owed. (It was uncommon in those days for businesses to take insurance as it was extremely expensive.) The other partners wanted to pay off their creditors at 25% and terminate the business but Farquhar proposed that he take over the company and all of its assets and liabilities. He then negotiated with creditors to be allowed to defer immediate partial payment in favor of rebuilding the business and paying them off 100% over time.

Philip A. and Samuel Small were the largest creditors and having been favorably impressed with young Farquhar they agreed. York was less than 8,700 population at this time and people were knowledgeable of one another either first hand or by reputation. Once the influential Smalls agreed to this highly unusual proposal, the other creditors followed. Farquhar leased a warehouse, got additional credit to fit it out for a shop and went into business. Within four years he had repaid 100% of all debt from the Dingee Company and from starting up his company.

Farquhar was smart, had initiative, and was willing to take chances. As 6,000 Confederate troops were approaching York in June of 1863 Farquhar had just turned 25 years old, had been married less than two years and had a one-year old son. He was working 18+ hours a day rebuilding a business that had been totally destroyed seven months before and was making progress paying off the Dingee Company’s creditors when the threat of York, and of his business, being burned became a very real possibility. Resistance was not an option as York was undefended because Union troops had been sent elsewhere. On the morning of June 27th the town was informed the Confederates would arrive that night or the next day. Farquhar went to the Committee of Public Safety run by the town leaders and suggested that better surrender terms could be achieved through an advance negotiation than after the Confederates had arrived and saw how much of York’s property and wealth was still available in the town for the taking. The Committee said his plan was good enough if anyone would go, and if the Confederates would keep the bargain that was made. Farquhar said he would go and make the arrangement and believed it would be honored. The Committee did not take him seriously. Farquhar then told them he would take the responsibility himself and go anyway, which he did, likely surprising the Committee. Farquhar rode 18 miles to the Confederates and negotiated the terms of York’s surrender, returning that afternoon to report to the York Committee. As Farquhar had no standing on the Committee, later that same day several Committee members returned to the Confederate camp, now eight miles west of York, and formally confirmed the agreement.

In March 2022 Jim McClure wrote a piece on the surrender and discussed whether he had been fair in his assessment of Farquhar over the years. He questioned whether he was guilty of lapsing into the practice of “presentism”, the tendency to unduly or unfairly interpret past events with modern values. In my opinion, yes, there is an element of presentism in his criticism of Farquhar. In fairness, though, it seems unavoidable that any modern person who attempts to analyze a 19th century event will, to some degree, interpret it through contemporary sensibilities and 20/20 hindsight. In his piece McClure also states, “Further, sometimes historians lose a sense of generosity when assessing the past.” I believe A. B. Farquhar’s role in the surrender of York tends to be viewed without any sense of generosity nor with an appreciation of this young man’s situation and character.

Farquhar’s many civic contributions and his advocacy for the advancement of York for the remainder of his life should be a part of contemporary York citizens’ knowledge of this man. The company he founded in 1862, Pennsylvania Agricultural Works, later A.B. Farquhar Company, was the largest employer in York County by 1899 and provided thousands of local jobs and world-wide distribution of its machinery brought much revenue into York for the 90 years of its existence. He supported parks, the symphony and opera and numerous charitable and social causes. He believed in the future of York and wrote a piece in The Gazette, June 11, 1891, “What York May Be—A Dream of a Bright Future for the Town; the Power of Beauty”, encouraging public and private support for beautification of the city and cultural enhancements for everyone. He was a committed family man and deeply regretted not being able to spend more time with his young children due to his demanding work schedule. After he handed over management of the company to his son, Francis, in the 1910s and until his death in 1925 he spent much time with his three grandchildren. He was devastated when his first grandson, Arthur, a brilliant student and avid ornithologist and nature lover, died in 1918 at age 16 from pneumonia.

A. B. Farquhar was a human being, therefore not perfect, but for the whole of his life he strove to do what he believed to be the correct and moral thing for his family, his business, his employees and for York and all benefitted from his efforts. He deserves to be remembered for all of this and not just his role in the surrender of York.

Debra Kleyhauer lives in Spring Garden Township.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: Why did A.B. Farquhar surrender York Pa. to the Confederates?