Why did Cincinnati never finish its subway?

The story of Cincinnati’s unfinished subway has been built up to legendary status. Rumors and questions about why it was never completed, if it can ever be used and what’s really down there have kept the topic alive for nearly 100 years.

The project was abandoned in 1929 with only 2.2 miles of twin tracks laid underneath Central Parkway. If you look close, boarded-up tunnel openings are still visible from Interstate-75, near the Harrison Avenue exit.

The Cincinnati Museum Center used to offer tours into the catacombs of darkened concrete tunnels. The Enquirer has several photos of what’s down there: ghost stations with graffiti tags, a bomb shelter from the 1960s, water mains and fiber-optic lines that crisscross the city.

But never any subway trains.

Why was the subway project canceled? How did it go from a rapid transit system necessary for the growth of the city, supported by politicians, newspapers and voters, to Cincinnati’s “white elephant”?

To understand the subway, we have to start at the canal.

Our history: Downtown Cincinnati: What the past tells us

A canal called Rhine

The Miami & Erie Canal ran along where Central Parkway is today as part of an inland waterway connecting Lake Erie to the Ohio River. The idea had been suggested by George Washington in the 1780s as a vital link in a transportation system to carry passengers and cargo from the northeast to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico.

Construction of the western route of the canal began in 1825 in Middletown and reached downtown Cincinnati in 1829.

The canal skirted the city, bent at the Plum Street “elbow,” crossed the city to Sycamore Street, then took a diagonal path (now Eggleston Avenue) to empty into the Ohio River near the site of the Daniel Carter Beard Bridge.

The Germans who settled north of the canal called it the Rhine, after the river in Germany.

And the neighborhood then became Over-the-Rhine.

Canal boats were not the fastest or most comfortable form of transport. The boats were 90 feet long and 15 feet wide and could float on as little as four feet of water, pulled by a single mule that walked along a towpath at a speed of two and a half miles per hour. At each change in elevation, a boat had to be steered into a lock, a chamber where the water level was raised or lowered, before it could continue on its journey. It was a bumpy, tiresome process.

The canal was successful, for a while. In the mid-19th century, Cincinnati was the largest city in the west and the canal helped it thrive as a major manufacturing center. By the 1850s, though, steam trains replaced the canals for long-distance passenger travel, and the canal was on the way out.

Rarely used other than for shipping bulk cargo, the slow-moving canals became mucky, polluted cesspools and health hazards. Yet that didn’t stop children from swimming in the foul waters.

Dream of a subway

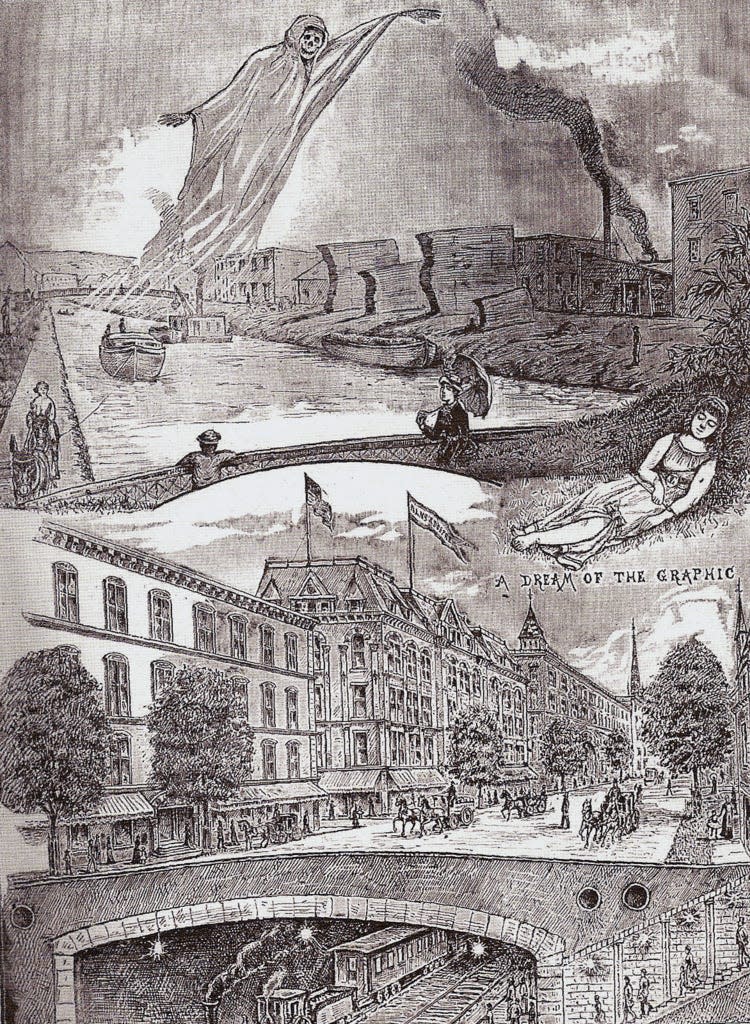

Historians trace the origin of the idea for a local subway to the Sept. 27, 1884, edition of the Cincinnati Graphic, a weekly magazine. Editors called to get rid of the canal and offered an illustration called “A Dream of the Graphic” that depicted the ghostly specter of death hovering above the filthy canal while a woman dreamed of a scenic boulevard over an underground steam-powered railroad.

The boulevard idea resurfaced in the 1907 report, “A Park System for the City of Cincinnati,” prepared by German landscape architect George Kessler, with plans for several city parks. The Kessler Plan proposed the creation of Central Parkway, “a wide passage into the very heart of its business center” that would occupy the right-of-way of the unsightly canal.

Kessler described “a grand boulevard 150 feet wide over all, with a driveway on each side of a continuous central park space, the latter to be diversified and embellished with gardens, fountains and other features.” There was no subway included in the plan.

That came a few years later. Cincinnati at that time was served by nine interurban electric railways that connected to other nearby communities but did not run within the city.

In 1911, City Council requested that the State of Ohio lease portions of the canal to the city for use in creating a rapid transit railway to transport people from the outskirts into the city.

Politics and war

But the politics were complicated. Since the 1880s, Cincinnati had essentially been run by George Barnsdale Cox, a Republican boss who operated a political machine of influence and corruption. The Reform Democrats put up Henry T. Hunt as a mayoral candidate in 1911 and finally broke Boss Cox’s hold.

Hunt was a champion of the subway plan and appointed a three-person Interurban Rapid Transit Commission. Although Hunt lost re-election in 1913, the Cox Republicans were also on board for the subway.

The city chose a plan for a 16.46-mile rapid transit loop that would begin at Fourth and Walnut streets, run north on Walnut to the canal, follow the canal bed to Ludlow Avenue, pass through St. Bernard and Norwood, then come down Madison Road, follow Columbia to downtown at Third Street and back to Walnut. It wasn’t a true subway, because only the portions under Central Parkway would be underground.

Voters approved a $6 million bond issue in 1916, but World War I erupted before work began. When the war was over, the cost of materials had doubled, but taxpayers were unwilling to budge. Plans were scaled back again to focus on the western portion of the route, the section that would support Central Parkway.

Construction finally began on Jan. 28, 1920, with the subway tracks laid in the canal bed.

“The subways will mean a bigger and better city in which to live,” The Enquirer quoted Charles W. Dabney, president of the University of Cincinnati, as an example of the sentiment at the time. “It is true that it will be a slight burden on the next generation to pay for the project, but they will be the ones who will benefit by the improvement. There must be a change if Cincinnati intends to keep pace with other large cities.”

Delays and problems brought unexpected costs. The digging caused erosion on surrounding hills that cracked apart a few houses in Brighton. Cincinnati had to negotiate with the cities of St. Bernard and Norwood. Construction dragged on for years as the money ran out.

In 1926, the progressive Charter Party led by Mayor Murray Seasongood wrote a new city charter to sweep out the corruption in City Hall. Seasongood considered the Rapid Transit Commission a holdover from the Boss Cox era and ordered a new study of the city’s rapid transit needs in 1927.

More: Isaiah Rogers, the major Cincinnati architect you don’t know

The Beeler Report concluded that Cincinnati may not be a large city, but the hills and its role as an industrial center made rapid transit a necessity. The report warned that it would take another $10.6 million to complete the subway. Seasongood wanted work stopped until the Rapid Transit Commission ended on Jan.1, 1929.

Meanwhile, Central Parkway opened to great fanfare in October 1928, though with significantly less greenspace than originally envisioned.

The stock market crash in October 1929 put an end to the subway as the nation sunk into the Great Depression.

More: Floating Palace circus boat built in Cincinnati was the talk of the Midwest in 1850s

Not part of the plan

Attempts to recharge rapid transit fell short. Connect it to the streetcar lines? The streetcars were too long to maneuver the subway’s curves. Open it up to automobile traffic? Exhaust fumes and the psychology of drivers steering through dark, narrow tunnels wouldn’t work.

A study by the Engineers’ Club of Cincinnati in 1936 determined that the rapid transit system had been designed for the needs of the 1910s, and 20 years later needed to update for current needs or “it should be forgotten – as part of the toll of progress.”

The final nail was the Cincinnati Metropolitan Master Plan from 1948 that did not include rapid transit but proposed the Mill Creek Expressway (now known as Interstate 75), which ran parallel to the existing subway route as the best solution to the city’s traffic problems.

Cars won out over a subway.

In an Enquirer editorial from Nov. 20, 1948, titled, “Pointless Now,” editors wrote: “The whole concept of mass transportation has changed since the subway was begun, and if the project were completed now it would do very little to solve the basic problems to be faced in this year and coming years. Streetcars are heading toward oblivion. The interurban electric cars for which the subway primarily was designed already have passed into the limbo. And while the completion of the subway would provide a very convenient underground downtown terminus for streetcars and busses it would not materially speed the movement of traffic and people to, from and through the city.”

The $6 million bond approved for the subway was not paid off until 1966, with an additional $7 million paid in interest.

Transit authorities hoped to use the subway tunnels for a proposed light-rail in 2002, but voters rejected it.

A different city grew up without the subway. What would have happened if it had been completed? Would Cincinnati have become a major metropolis? Would there be a network of rapid transit lines reaching to Price Hill, Hyde Park, Avondale, West Chester? Or would it have sat underutilized with cars still dominating local transportation?

The what-ifs are part of what draws so much interest in the abandoned subway. We may know why it wasn’t finished, but some questions have no answers.

Sources: “The Cincinnati Subway: History of Rapid Transit” by Allen J. Singer, “Cincinnati’s Incomplete Subway: The Complete History” by Jacob R. Mecklenborg, City of Cincinnati archives, Enquirer archives.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Cincinnati subway: Why it was never finished