Why did Sacramento take this woman’s family photos and childhood Bible in a homeless sweep?

Nicole Casper, whose RV was towed without warning by the city of Sacramento with almost everything she owned still inside it, retrieved some of her possessions from the impound lot Tuesday — but had her access cut off before she retrieved the suitcase in which she frantically had packed her family photos and her childhood Bible.

Her Winnebago was set to be demolished two days later, and she walked onto the lot the same day that Chima’s Tow employees were set to begin throwing her property in the garbage.

Iran Chima of Chima’s Tow previously told her that, because all of her property was being reclassified as trash on Tuesday, she would be allowed to take it with her. When she was partway through moving out her belongings, Chima abruptly revoked her access to the RV. Earlier in the day, he said he “didn’t agree with” the deal he had made with her.

Casper, 42, navigated two weeks of hurdles to recover some of her personal items from the tow yard. Like many unhoused people, she was not the registered owner of the RV she called home for three years, and so, on paper, she had no right to her family photo albums or anything else inside the Winnebago once the city impounded her home with no notice.

That bureaucratic wall puts Casper in the same position as many other homeless people, who are often not the registered owners of their homes and thus have little to no recourse when the Sacramento seizes them during these evictions or “sweeps.” Crystal Sanchez, president of the Sacramento Homeless Union, said that any personal property left inside the vehicles — which could include important documents, medication, sentimental items and survival gear — often ends up in the dump.

Ultimately, Casper was only able to retrieve anything because Chima decided to let her onto the lot after being questioned by a reporter. A week after making that deal, he told her she would not be allowed back on the lot when she was midway through packing.

Casper found the city’s unannounced sweep and its aftermath “beyond hurtful — it’s devastating.” In the sweep, she lost virtually everything she owned and was forced to beg for her own childhood Bible, which she had no actual right to claim.

But she reached out to The Sacramento Bee because she hoped telling her story might lead to change.

“I know I’m not the only one that it’s happened to,” Casper said. “I do feel like somebody needs to say something because like I said, it doesn’t feel right. And I don’t think it is right, the way they’re going about doing it. There’s got to be a different way, a better way.

“I mean, we’re people.”

What happened at the impound lot?

A Sacramento spokeswoman, Kelli Trapani, confirmed that on Jan. 23, city code enforcement officials demanded immediate tows of 13 vehicles on Opportunity Street with registration that had expired at least six months ago. Casper’s RV violated that part of California Vehicle Code. She and two neighbors said people on the street were given 15 minutes to get all their things out of their homes.

Trapani said code enforcement usually gives people 30 minutes to an hour to get their things, although the timing, she added, depends on whether the tow truck has already arrived. Often, code enforcement gives 72-hour notices of tows, which it did for some people in this sweep. Vehicles with violations other than the overly expired registration were given a three-day warning. The street had also been visited by code enforcement in December, though Casper and three neighbors from the street said the officer at that time gave a vague warning.

After the sweep, Casper raced to pull her life back together. She had initially been told that she would not be able to retrieve any of her items from the Winnebago. She arrived at the tow company with two Bee reporters almost a week after her home was seized. Chima at first told her she could not have her things because she was not the registered owner of the vehicles. A big red sign on the wall reiterated the point.

Ultimately, he changed his mind and told her she could come back to unpack the entire Winnebago where she had lived for three years. He said it would save his employees the trouble of having to throw her items away.

She returned to Chima’s Tow a week later. She wouldn’t have even made it to the lot if Tess Cauvan, a retiree who had read Casper’s story in The Bee, hadn’t stepped in at the last minute to give her a ride: Casper’s friend, who was supposed to drive her to Chima’s Tow, didn’t answer his phone that morning. Once she arrived at the lot, Casper was almost denied access to the RV again, as Chima was not on site. A little before 11 a.m., she was led onto the lot.

Although Cauvan and another Bee reader, Linda Derksen, had learned her story days earlier and showed up on Tuesday to lend her a hand, neither was allowed to help her unload the vehicle.

Casper gathered her belongings alone while Cauvan and Linda Derksen waited outside the fence.

After spending two hours in the lot, Casper rolled out a large cart stacked with bags of her belongings. Chima stood off to the side.

She rolled the cart toward Cauvan’s SUV, and a bag of markers fell off and directly into a muddy puddle. Cauvan and Casper fished the art supplies and a crochet hook out of the water.

Chima watched as Cauvan, Derksen and Casper loaded everything from the cart into Cauvan’s SUV.

Once the car was loaded, Chima asked that Casper produce her vehicle’s title, which no one had previously asked her for. The document, she said, was somewhere among the many bags she had packed alone and in a hurry and then loaded into Cauvan’s car.

Casper said that his request was unreasonable.

Chima insisted that she retrieve it. “It takes a second,” he said, gesturing at the back of the SUV that was full of bags.

“No,” she told him. “I’m not gonna do that.”

Asked why he needed the title now, he turned to the reporter with her and said he could explain “in private.” Casper snapped, “Why? Am I a child? You can’t talk to me?”

“I’m giving you help,” he told Casper, his voice raised. He turned to Cauvan. He said, “We need to verify what she said is correct. Did she actually buy it?”

He had already overseen Casper moving a substantial amount of items from the RV into Cauvan’s car. Casper said she would not pull apart the bags to search for the document.

“I think we’re done,” Chima said. “Have a good day.”

Casper said, “I’m not gonna stand here and work like a slave just because you want me to.”

She stood on the other side of the SUV, rattled.

“He just wants to put me through another fire hoop,” she said. “It’s no reason for it. They’re gonna demolish it in a day.”

Cauvan drove her away. Derksen, who had been at the ready in a white pickup, drove off alone.

The two volunteers had said they showed up to help Casper because they saw themselves in her. Derksen said people in her past had given her a hand when she needed one, and she wanted to “pay it forward.” They both agreed that many people are just one calamity away from homelessness themselves.

“You don’t know how close you can be,” Derksen said.

Casper said that later, when she finished unpacking the bags, she realized that the suitcase she had left behind was the suitcase with the vehicle’s title, along with her Bible and her family photos.

Renewed calls for an end to sweeps

Since the city towed her home, Casper has temporarily moved into a friend’s overcrowded apartment, where she sleeps on the floor. She’s not sure how long she can stay in the apartment, along with her friend’s wife and their four children.

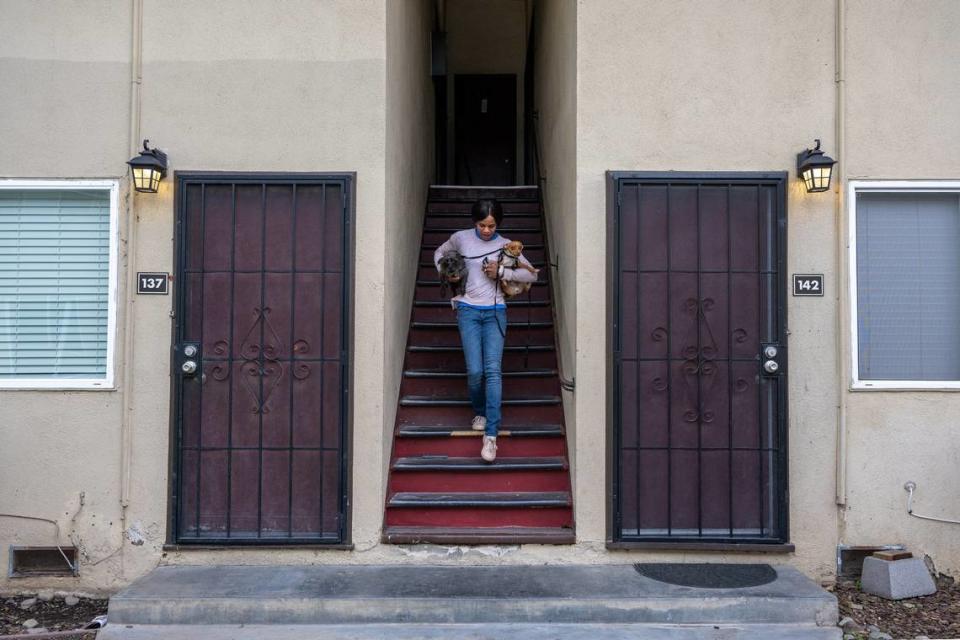

The Winnebago had offered her a sense of stability and security for the past three years, she said. Of the sweep, she said, “It’s a tragic and traumatic thing — an experience that I would not wish on anybody.” She feared that she and her two dogs, Gucci and Yoda, would end up in a tent.

“I was houseless, but now I’m homeless,” she said.

Casper’s story has led some advocates to renew calls for a halt to city sweeps.

Bob Erlenbusch, executive director of the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness and a leader of the Services Not Sweeps Coalition, called on Mayor Darrell Steinberg and the members of City Council to declare a moratorium on sweeps, which he called “heartless.”

He also demanded in an email that the city and county “immediately create the ‘Casper Fund,’ in honor of Ms. Casper, to fund mechanics to fix homeless people’s vehicles so they can move and not violate parking regulations, as well as support homeless people bringing their registration up to date so they are in compliance, so they do not have their home and their possessions crushed by a hydraulic compactor.”

Previously, spokeswoman Trapani said, “Sacramento strives to treat all people with dignity and respect.”

Casper said that the city fell short in treating her with dignity and respect. She was left without her shelter, in the middle of Sacramento’s rainy season. On the day of the sweep, she said, a social services worker drove away as she tried to flag him down. She said she was never offered any services or shelter the day the city seized her shelter.

“Now I’m going to be the person on the sidewalk,” she said. “How is that a win? It’s just adding to the problem. I feel like they just want to drive me crazy.”

Though she said the city did not help her, two weeks after the sweep, Cauvan — a retiree who read about Casper in the newspaper — gave her a lift back to the overcrowded apartment where she sleeps on the floor. The next day, it rained again. Casper has been trying to find a free or cheap trailer or RV, but she can’t afford much, and she isn’t sure what she’ll do once she has to leave her friend’s apartment.

She got some of her belongings back, mostly by luck. After the sweep, she has no home to keep them in.