Why does the delta variant spread so fast?

The delta variant spreads much faster than other Covid-19 strains—and scientists may now know why.

People infected with the delta variant have more than 1,260 times the viral load—the concentration of viral particles in the body—than those with the original strain found in China, a group of scientists has reported in a preprint paper. A higher viral load can have many implications such as more severe disease. Its most significant contribution is to a virus’s higher transmissibility.

Scientists at China’s Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention found, traced, and isolated 62 cases of the delta variant and conducted daily RT-PCR tests on those infected. These samples were then compared with data from the early 2020 outbreak in China, science journal Nature reported.

While conclusive studies about the delta variant, first found in India and dubbed by the World Health Organization as the “fastest and fittest” strain so far, will take more time, this analysis from Guangzhou has important public health implications.

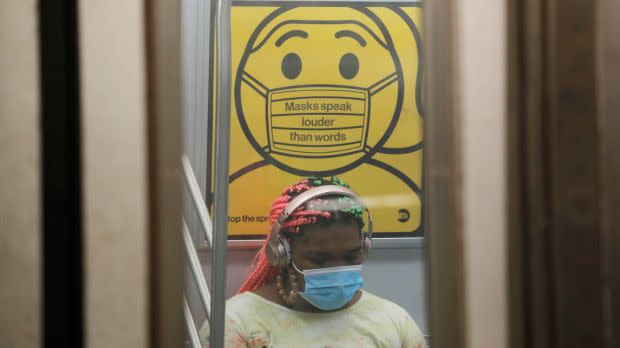

For one, it explains why cases shot up suddenly and significantly in countries where the delta variant has spread. Even in countries like Israel, the US, and the UK, with substantial proportions of populations vaccinated, the variant is causing cases to rise. Though severe cases and hospitalisations have remained low, the surge indicates the resilience of the variant despite vaccine-induced immunity. It also means that countries like the US are considering bringing masks back in public spaces even for those who are fully vaccinated.

Delta variant infections occur sooner

The analysis from China also suggests that samples of delta variant infections turn RT-PCR positive sooner than non-delta infections. To arrive at this conclusion, researchers relied on strict contract tracing measures.

When a centrally quarantined person turned positive on the RT-PCR, scientists immediately traced and tested their contacts. In the initial days of a Covid-19 infection, the viral load may be too low to be picked up on a test. These contacts were tested daily for the researchers to examine the duration between when a person might have been infected and when they finally test positive.

In the case of the delta variant, these infections showed up as positive on the test four days after the suspected infection. In non-delta infections from 2020, these tests came out to be positive after six days.

A shorter interval between suspected infection and test positivity indicates that the delta variant also has a shorter incubation time. When the viral load is too low during the initial days, it also means that the person may not be as infectious as they are once the virus particles in the body are high enough to be detected on a test.

Now, with the delta variant, when a test turns positive sooner, it means two things. One, the virus replicates faster and increases the viral load. Two, it becomes infectious sooner, and thus, spreads faster. “Knowing when an infected person can transmit is essential for designing intervention strategies that break chains of transmission,” the researchers noted in the preprint.

This has public health implications, too. A shorter incubation period would mean that a test that is taken 72 hours prior to travel—a norm for most international travel at the moment—may be too long a window for the delta variant. “…The provincial government required people leaving Guangzhou city from airports, train stations, and shuttle bus stations to show proof of a negative Covid-19 test within 72 hours on June 6 and this was shortened to 48 hours on June 7,” they noted in the preprint. “In contrast, the comparable time window implemented in the 2020 epidemic was seven days.”

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz:

Will sending its largest-ever contingent change India’s fortunes at the Olympics?

The two biggest names at the Tokyo Olympics stumbled on the same day