Why does Oregon need a Habitat Conservation Plan to govern state forests?

Finding a compromise is never easy, particularly when it comes to Oregon's state forests.

For years, the Oregon Department of Forestry has attempted to strike a balance between habitat protection and logging. Now, the agency has developed a master plan that if adopted would govern about 640,000 acres of state forest for the next 70 years plus 94,206 acres the agency is likely to add during that term. ODF manages 745,000 acres of state forest lands across Oregon, according to its website.

ODF's idea has a simple name: Habitat Conservation Plan. The plan has become the latest flashpoint over how many trees can be cut and which to leave for the state's wildlife.

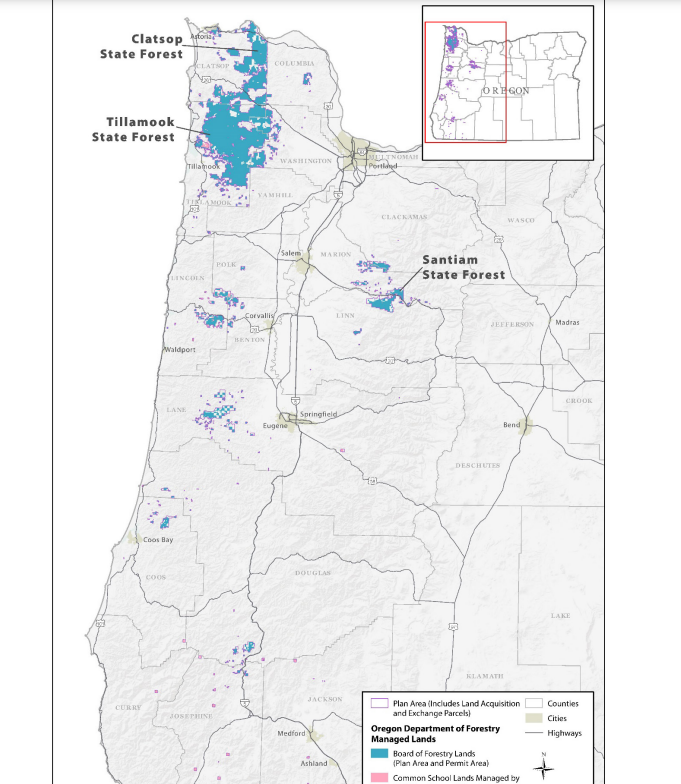

The proposed HCP area is west of the Cascades with large swaths in the northwestern corner of the state in Clatsop and Tillamook counties.

From 2011 to 2021, Oregon averaged 3.8 billion board feet harvested across all land types, with state forests accounting for 6.5% of the harvest on average. State forest lumber harvests are a drop in the bucket when taken at face value, but the revenue they create is crucial in some areas of the state.

For rural counties that rely on revenue from logging on state forest lands, the HCP means less board feet cut over time, which could mean less money to fund police, schools, social services and more.

At an OBF meeting in March, former candidate for governor Betsy Johnson and a convoy of about 100 loggers, timber owners and students blasted the plan. “Communities in Northwest Oregon have gone from incredulous to furious over how this HCP has been handled,” said Johnson, whose family has also been in the logging business. “Rural Oregonians do feel like this plan is being shoved down their throats.”

Environmental groups say the plan is important for habitat conservation. “It assures long-term protection and enhancement for habitat and also allows other forest uses to continue, like logging,” said Michael Lang, Oregon senior policy manager for the Wild Salmon Center. “That is truly a compromise.”

The plan has become one of the biggest environmental policy controversies since protections for the spotted owl ignited the so-called timber wars in the 1980s and '90s.

The Oregon Board of Forestry was set to vote on the future of the plan this fall. Now, the plan may not be adopted until April or May of 2024 due to staffing issues at the federal agencies overseeing the plan's approval, according to OBF chair Jim Kelly.

"I don't think that there is any real explanation beyond that. There's been no essential restructuring of the HCP," Kelly said.

Public comment will remain open until a decision on the plan is made and can be submitted through the ODF website.

Why have a Habitat Conservation Plan?

The HCP is aimed at maintaining habitat for federally listed terrestrial and aquatic species like the marbled murrelet, spotted owl and chinook salmon while managing logging, recreation and other forest activities.

One of the reasons to have an HCP is legal pressure.

ODF has been in the crosshairs of several lawsuits for violations of the Endangered Species Act, including most recently a settlement with The Center for Biological Diversity, Cascadia Wildlands and Native Fish Society over the effect of stream-side logging on endangered fish.

For the ODF, which manages hundreds of acres of state forest that is home to several listed species, the HCP would come with an incidental take permit.

"It is a way to comply with the Endangered Species Act that brings about a lot of certainty in terms of what you're going to have to do for species now and in the future," said Mike Wilson, state forest division chief with the ODF.

The HCP lists 17 covered species, which utilize land or streams during their lifespans. Some of the species are listed as threatened or endangered federally or statewide, while others are likely to be listed during the HCP’s 70-year term.

If the HCP becomes the ODF’s new management plan, the incidental take permit would apply to all of them, safeguarding the agency from lawsuits over the Endangered Species Act for decades.

"Some of the 17 species that are on our HCP are not yet listed, but they're on the plan for the Fish and Wildlife Service to assess and determine if they warrant listing," Wilson said. He added that over the 70-year timeframe, the permit can be amended to include more species if needed.

Conservation efforts

ODF would take on numerous conservation efforts as part of its HCP, allowing the agency to further comply with the Endangered Species Act. These include riparian area conservation, stream enhancement, fish passage projects, and designated habitat conservation areas.

The two initiatives most likely to interfere with commercial timber activities are riparian programs and habitat conservation areas.

With the establishment of riparian conservation areas, commercial timber harvests would no longer be allowed to take place in the areas that border streams. The width of the protected area would vary from 35 to 120 feet, depending on the stream. This comes amid concerns on the effects of logging near streams on endangered anadromous fish.

“Logging close to salmon-bearing streams or even their tributaries reduces the amount of shade over the river, and first of all that increases water temperature,” Lang said. “Salmon are very temperature dependent and they cannot survive in warm water.”

Lang said logging in steep areas beside streams introduces additional hazards to fish-bearing waters. This practice, he said, can increase the risk of landslides, which pour sediment into the creek and cover gravel, salmon-spawning grounds with silt, killing any eggs in the process.

Under the plan, ODF would designate 275,000 acres of land as habitat conservation areas for endangered and threatened terrestrial species like the marbled murrelet, red tree vole, northern spotted owl and coastal marten. On this land, which makes up 43% of the total area, timber harvesting would no longer be permitted.

“The habitat conservation areas, like the uplands and riparian zones, are places where you can grow big old trees and store carbon and improve water filtration into streams,” said Casey Kulla, state forest policy coordinator with Oregon Wild. “Ultimately, it’s going to be the best for the survival of the forest and fish, which is why you have a Habitat Conservation Plan.”

While the plan would decrease the land available for logging in the state forests, it does not address land already sold for logging but not yet harvested. The ODF says there is roughly 300 million board feet of timber that fits this description. Wilson says this surplus lumber is significant when looking at the short-term effects of an HCP.

"So it is good news in that during the next couple of years, as we transition to the HCP, we're going to have lower planned harvest levels than we have had over the past decade, but having that extra volume on contract, since it hasn't been harvested yet, will certainly help to smooth out the bump there," Wilson said.

How would an HCP affect timber harvests?

Habitat conservation areas and riparian conservation stream buffers mean less land for logging. While timber harvests would continue to exist in the state forests, the plan’s overall effect on the industry has been disputed.

Timber groups say they were originally told the plan would allow harvest of 225 to 250 million board feet of timber annually — close to the most recent 10 year average. However, projected harvest levels of 165 to 182.5 million board feet for 2024 and 2025, incorporating elements of the plan, have sounded alarm bells across Oregon’s forestry sector.

ODF previously told the Statesman Journal the long-term logging levels wouldn’t necessarily stay as low as cited for 2024 and 2025.

“The data (they) cited applies to the next two fiscal years, which set target harvest volumes across the stated time,” said Jason Cox, a spokesman for ODF. “While they do incorporate conservation measures included in the proposed Habitat Conservation Plan, these represent a two-year snapshot in time, not the anticipated average harvest volume over the 70-year term of the HCP.”

In 2022, ODF issued an Environmental Impact Statement for the HCP. The EIS model projected a state forest harvest volume of 247 million board feet in years 1-25, 222 million board feet in years 26-50 and 204 million board feet in years 51-70.

Timber advocates say initial models didn’t correctly factor in the HCP restrictions which are now reflected in the projections with bigger reductions.

"All of our mills in Oregon rely on state timber, and it's an enormous proportion of the wood fiber that we need to operate," said Kristin Rasmussen of Hampton Lumber, a timber processing company that owns four mills in Oregon and six others across the northwest and British Columbia. "Reductions of the scale we are talking about with the HCP would be a big problem."

How would an HCP affect Oregon communities?

Revenue from state forest timber is distributed directly to ODF and to the trust land counties, which are the counties and communities that overlap with the state forests. Around 60% of the revenue goes to the trust land counties and around 37% goes back to ODF. Timber advocates and some people in those counties that rely on the revenue from the state forests say a decrease in lumber harvests would be destructive to their communities.

“Tillamook County, Clatsop County and Washington County are the biggest recipients of state forest land timber revenue, and we kind of go back and forth between Tillamook and Clatsop as to who gets the most,” Tillamook County Commissioner David Yamamoto said.

“(The HCP) would decimate the trust counties,” Yamamoto said.

Sara Duncan, director of communications at the Oregon Forest Industries Council, a trade association representing forestland owners and forest products manufacturers, said the counties that could be impacted are already struggling to provide services. “Everybody agrees that the HCP is probably a good course of action for the department ... but the question is what is the best outcome for Oregonians?”

Rep. Cyrus Javadi, R-Astoria, and Sen. Suzanne Weber, R-Tillamook, who represent the North Coast, as well as Clatsop County Sheriff Matt Phillips and some Clatsop County commissioners, have been vocal in their opposition to the plan.

Gov. Tina Kotek, in response to a letter from Republican state legislators, urging consideration of an alternate plan allowing more logging, called for those involved to "come together to find a better, more balanced approach."

"The fiscal impacts and unintended consequences of an outdated funding model," Kotek said, "needs to be reexamined in light of the fact that our state forests today must be managed for a multitude of public values that were not accounted for in the current funding structure."

According to Yamamoto, Tillamook County has brought in an average of $16 million to $17 million in state forest timber revenue per year over the last 10 years. For the county’s communities, it’s a precious resource.

Timber also is a vital employer in those three counties.

“For some of those mills, a drop in that state forest fiber supply could cost them the mill,” Duncan said. “These are real peoples’ jobs. That mill, and those 150 or 200 people who work at that mill, are really important to those communities. Many of those small towns are built around the mill.”

Hampton Lumber's mills in Banks, Willamina, Tillamook and Warrenton employ hundreds throughout the trust land counties with salaries and job benefits that can support a family. Rasmussen said 20-25% of the company's lumber comes from state forests, but at some mills, the amount is bigger.

She estimated the Banks mill, which employs roughly 65 people, gets about 50% of its lumber from state forests.

"This is a very volatile industry, it's a difficult industry to be in now and I think when you start talking about taking more and more state forest timber harvests away, you're just increasing vulnerability, not only for the manufacturers but for all of those businesses and people that depend on this revenue coming in," Rasmussen said.

What happens next for the HCP?

Before being adopted, the HCP needs to go through approval with federal agencies, like NOAA Fisheries and U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. After reviewing and approving the HCP, federal agencies issue an incidental take permit.

“There’s a lot of painful history here,” said Kelly, who supports the HCP or a compromise.

“As someone with a background in private business, I just shake my head,” Kelly said of the process, which began in 2017. “It’s stunning how long it takes, and I wish I knew why. It’s a long, difficult process.”

Kelly said he hopes a compromise is found but predicted no one will be "particularly happy."

“With the politics of this, it’s really divided," he said. "But our goal is to handle ourselves the way Republicans and Democrats did many decades ago, back in the time of Tom McCall, the Oregon Way, by finding common ground. But that’s easier said than done.”

Charles Gearing is a former outdoors journalism intern at the Statesman Journal.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: What would Oregon's Habitat Conservation Plan do for state forests?