Why doesn’t Jupiter have even more spectacular rings than Saturn?

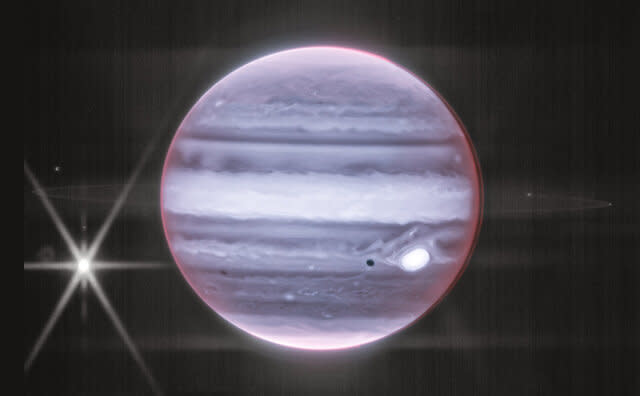

Just recently on the blog I posted a series of images of Jupiter taken by JWST, some of which showed Jupiter’s faint ring.

I don’t think a lot of people know that all four giant planets in our solar system have rings; Saturn’s are by far the most obvious, but Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune own a set themselves. As I wrote in that article, Jupiter’s main ring is primarily made of dust, and may be due to small particles impacting the two moons Metis and Adrastea; sunlight would push on the dust particles and remove them rapidly, so they must be replenished on a similar timescale.

But… Jupiter is about three times more massive than Saturn, so its gravity is much stronger. You’d expect it to have a much larger ring system. Why doesn’t it?

New research just published puts the blame on Jupiter’s moons.

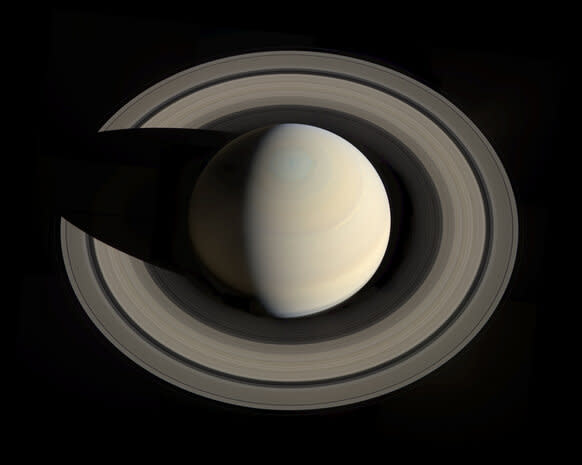

S A T U R N. Credit: NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute / GordanUgarkovic

Now, we don’t know exactly what formed Saturn’s rings, but it might either be from comets that get close to the big planet and get disrupted, or from a collision of icy moons. Saturn’s rings are almost pure water ice. We know that comets hit Jupiter fairly often — several impacts have been seen over the years, though some may be from asteroids, but the 1994 impact by comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 was well observed.

So where are Jupiter’s rings?

In the new work [link to paper], they used a simulator that reproduces the effects of gravity on an orbiting particle or particles. They included not just the gravity of Jupiter but, critically, all four of its big moons, called the Galilean satellites: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. These moons range from decent-sized to enormous; Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system and is bigger then Mercury! So their gravitational influence is necessary to include, especially because any ring system would likely exist in proximity to them in terms of distance from Jupiter.

In the simulation they placed test ring particles around Jupiter, making them spherical with a diameter of about two meters, and put them in circular orbits over Jupiter’s equator. The distances ranged from about 110,000 km from Jupiter’s center all the way out to about 5 million kilometers. Any closer and Jupiter would tear the particles apart from tides — a distance called the Roche limit — and if they got much farther out then over time the Sun’s gravity would dominate over Jupiter’s — a distance called the Hill Radius.

They ran the code for a million and ten million simulated years, to really give things a chance to brew.

Combining multiple filters and stretching the contrast allows Jupiter’s faint dust ring and several moons to be seen in JWST observations processed by Judy Schmidt. Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and B. Holler and J. Stansberry (STScI), Judy Schmidt

What they found is that the chance of a ring particle surviving is pretty dang low any closer than about 2 million kilometers from Jupiter — for comparison, that’s five times farther out than the Moon from Earth. A long walk.

It’s more complicated than that; the particles can fall into orbits that have simple fractions of the moons’ orbital periods and in some cases that can provide some stability. But even then a particle is more likely to be gravitationally pumped by the moons and either flung out of Jupiter orbit or dropped into the planet itself. Overall they found that 30% of the test ring particles were lost very rapidly, in far less than one million years. 50% of the test ring particles were lost after about 3 million years, and it slows from there.

So, pretty much, after some tens of millions of years most of the rings would be gone. Even the ring Jupiter has now is at a distance the sims found to be unstable in the long run, so it’s either less than 10 million years old or, more likely, it’s replenished as I noted above.

Well, neat! But if Jupiter’s moons clean out the system rapidly, why hasn’t Saturn’s? The moons there are different. Unlike Jupiter with four massive moons, Saturn has only one very large moon, Titan — second only to Ganymede in size and mass. The next largest, Rhea, is smaller than our own Moon. They’re also farther out from Saturn, allowing the rings to exist closer in to the planet.

A collage of Jupiter and its four biggest moons, imaged by Voyager 1. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Incidentally, at the moment both Jupiter and Saturn have about 80 officially known moons, but it depends on how small an object you’re willing to call a “moon,” and how hard they are to find. They both likely have hundreds of orbiting bodies larger than 1 kilometer in diameter. But they’re very difficult to spot.

And if you’re willing to call a chunk of ice a meter or so across a moon, then Saturn has trillions of them. So maybe that definition needs to be a little fuzzy.

Everything in orbit around a planet interacts with everything else, and that can cause profound changes in that environment. This new work shows that this could mean no long-lasting, big, gaudy rings for Jupiter, while Saturn’s are stable for a long time. The team plans on repeating these simulations for Uranus, too, which presents other issues, since the planet orbits the Sun tipped over on its side.

It also raises the question of how many giant exoplanets orbiting other stars have rings, too, and what their systems look like. We can’t tell just yet, but we’re getting pretty good at observing these alien worlds. Maybe in a few years studies like this can extended a long, long way.