Why doesn’t Washington get hit by hurricanes? We asked a meteorologist for the answers

When Category 4 Hurricane Ian plowed into southwest Florida last week, it became the sixth hurricane of at least that strength to make landfall in the United States since 2017.

Ian also became the 46th Atlantic Ocean hurricane to achieve at least Category 4 status since the turn of the century, with many making landfall in the U.S.

#GOESEast captured this incredible view of the inside of #Hurricane #Ian's eye as the storm approached Florida.

Latest: https://t.co/FYrreOueMf#FLwx pic.twitter.com/ulAYnrtw9z— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) September 28, 2022

It’s now been seven years since the U.S. enjoyed a year in which no hurricanes hit the continental U.S., and there have been only 16 years where the U.S. has had that luxury.

As active as the southeast is during hurricane season, why does the Pacific Coast not bear the brunt of ocean-borne storms?

Over 4.8 million of Washington’s 7 million residents live in coastal portions of the state, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management, putting them in the direct line of a hurricane landfall.

Even residents who live further inland — such as the Tri-Cities, which are approximately 170 miles from the Pacific coast, or Spokane at 220 miles away — would be in danger of hurricane after effects.

For example, Hurricane Ida made landfall in southeast Louisiana last year and was still causing damage as an extratropical low in New York City, approximately 1,200 miles away. A couple of years earlier, Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas and caused flash flooding in Greeneville, North Carolina, about 1,000 miles away.

Inland Washington might not be close enough to the coast to be hit by strong winds from an ocean storm, but it would be close enough to feel the heavy after-effects of extratropical cyclones.

Hurricanes enjoy the warmth

As you might guess, the primary reason the Pacific Northwest doesn’t get hurricanes is that the storms use warm water as fuel, Mary Butwin, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Seattle, told McClatchy News.

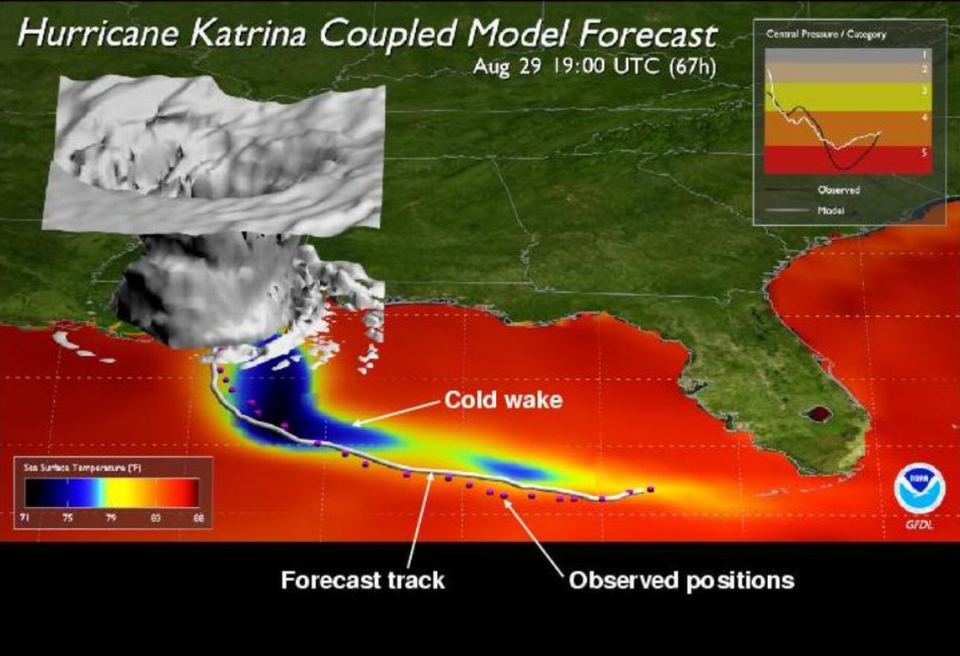

Warm water is vital for hurricanes because that’s how they get energy, according to NOAA. Hurricanes typically strengthen over warm water and leave cooler water in their wake, according to NOAA, which is why it says global warming and rising sea temperatures will contribute to stronger and more frequent hurricanes in the future.

Surface-level sea temperatures have to be at least 79 degrees for a hurricane to form, according to the Weather Service. The ocean waters along the West Coast are typically a chilly 50 to 65 degrees.

“To think about it in terms that we usually see here in western Washington, you have some warm water, and the heat from that will rise through the Sound, and then that will evaporate and rise up through the atmosphere,” Butwin said. And that’s basically the fuel.”

“Here, we usually see that in the form of fog,” she continued. “Warmer water forms those foggy conditions that typically happen over the Sound.”

That’s not to say tropical storms can’t form in the northeast Pacific every now and then. In 1975, a nameless hurricane formed from the remnants of Hurricane Ilsa northeast of Hawaii. The storm became the farthest-ever north Pacific hurricane and came close to the coast of Alaska, but it failed to make landfall after colliding with a cold front and falling apart.

Why is the water so cold off the West Coast?

It might make sense why water off the coast of Washington and Oregon would be chilly, but cold water persists all the way south to Cabo San Lucas at the tip of Mexico’s Baja California peninsula.

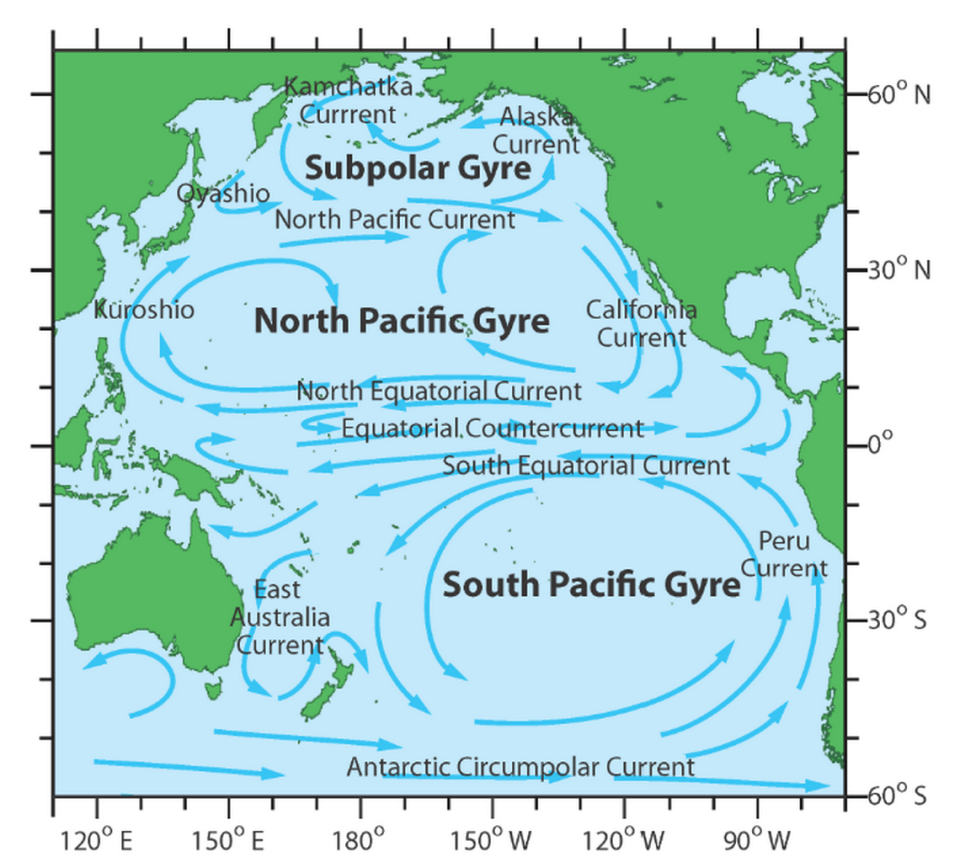

Cold water reaches that far south because of the North Pacific Gyre, a large rotating system with smaller rotating systems within it.

One of those smaller systems is the California Current.

“The main thing is for hurricanes, they form in the tropics, and you generally need the warmer ocean water, that serves as the fuel for the storm to form,” Butwin said. “We simply don’t have that; our ocean current is much too cold, generally coming down from the Gulf of Alaska.”

The cold water from Alaska is then pushed westward as it collides with warmer water from the North Equatorial Current and flows across the Pacific, until it reaches near the east coasts of Asia.

The water warms as it crosses the world’s biggest ocean, which is why typhoons — the name for a hurricane in the western Pacific — occur in the western Pacific but not in the eastern pacific.

The same phenomenon occurs in the Atlantic — the North Atlantic Gyre pulls water from northern Europe toward the African coast before pushing it west toward the Americas. Along this warm-water current, hurricanes form.

Wind also affects a hurricane’s path

Another primary reason why hurricanes mostly move from east to west — and therefore away from the U.S. West Coast — is because of trade winds. Trade winds result from the Coriolis Effect, the phenomenon that causes the worldwide circulation of wind that is created as the Earth rotates.

In most of the Northern Hemisphere, these trade winds blow from the northeast to the southwest, eventually blowing more easterly as they approach the equator.

Some trade winds — called westerlies — occur close to the poles and blow in the opposite direction. These winds, on rare instances, can blow storms back toward Europe, such as Hurricane Katia in 2011, which formed east of Florida, traveled north and eventually hit the United Kingdom.

Along with following the flow of warm water, hurricanes are typically pushed westward by these winds.