Why doesn't Al Oliver get more respect from the Baseball Hall of Fame? | Michael Arace

I was busted by the Baseball Writers Association of America’s fashion police in the press box at Fenway Park in 1987 or thereabouts. I was pulled over for wearing a (clean, crisp and fashionable) black T-Shirt.

The fashion policeman explained to me that BBWAA rules required that shirts be collared in Major League press boxes. This particular fashion policeman was wearing a white, polyester golf shirt with a BBWAA logo on the left breast and mustard stains on the lapels.

Such is the perception of the BBWAA: white, polyester-shirted, mustard-stained guardians of the game. The reality is different. The organization (of which I am not a member) is much more diverse, especially since it expanded to include online writers.

I respect the job the BBWAA did, and still does, in its job of electing Hall of Famers. Members who have been in good standing for at least 10 years get ballots. They vote on a pre-screened cast of players who had careers that stretched at least 10 years and who’ve been retired for at least five years.

I wish everyone who had a ballot made it public (many do) and outlined their criteria (many do not). While voters are growing increasingly transparent, more sunlight is always better.

The Hall of Fame Committee’s “character clause,” which was adopted in 1945 and states that players “shall be chosen on the basis of playing ability, sportsmanship, character, their contribution to the teams on which they played and to baseball in general,” is a source of ongoing debate.

There are those who feel that the clause is too vague. There are those who argue that it is an impossible regulation, given how things change over eras. And there are those who think the “character clause” is just fine. I’m in the latter camp. I think that it is imperfect, like the 1980s BBWAA fashion police, but it sustains a purpose.

I don’t believe Pete Rose, the all-time hits leader, should be in the Hall of Fame because he violated gambling rules that are posted on the front of every clubhouse door. In short, the sign says, “if you gamble on the game, you’re out.” I don’t believe Barry Bonds, arguably one of the best in the history of the game, should be in the Hall of Fame because his steroid use was a form of cheating. He, and others like him, cooked the record books.

Rose, Bonds and other tainted players who deserve to be in the Hall will eventually get in because a wider scope of history comes into play as the years go by. In this regard, the BBWAA process works as well as any. It marks time.

Scott Rolen, in his sixth year on the ballot, was elected to the Hall earlier this week. I paused when I heard the news. It felt like this was one of those years when the writers might have stretched, just a bit, to get at least one player elected. Was that the case? Rolen was one of the best defensive third basemen of all time and many of his offensive stats (home runs, RBIs, slugging percentage, WAR, OPS, OPS+) place him among the top dozen ever at his position.

There are a lot of stats now. Some of them are even useful tools for vetting Hall of Famers.

Rolen will be joined in the class of 2023 by Fred McGriff, who was voted in by a select, 16-member panel as a member of the “Contemporary Era,” those whose primary contribution to the game came in 1980 or later.

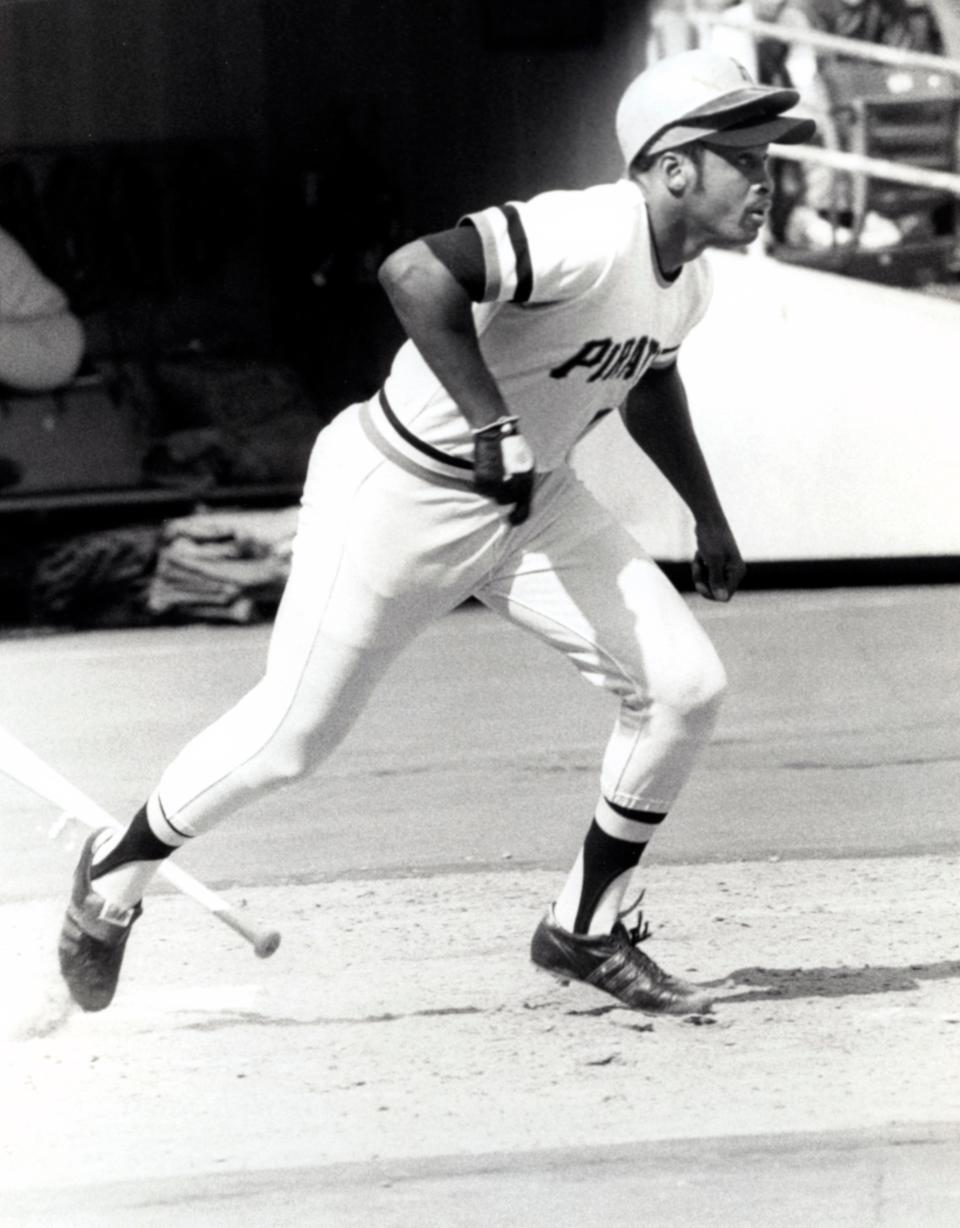

I always feel for Al Oliver at this time of year. He failed to get 5% of the vote when he first became eligible in 1991. He fell off the ballot then and, ever since, he has been shunted aside by the various iterations of the Veterans Committee.

“AO” was a professional hitter and a seven-time All-Star. He led the National League with a .331 average and 109 RBIs in 1982. His career numbers – .303 average, 219 homers,1,326 RBIs, 529 doubles and 4,083 total bases – range from strong to very strong.

He is a borderline Hall of Famer, in my view, but he gets little respect.

Someday, the MLB’s view of Rose’s gambling, and the BBWAA’s view of PDAs and Bonds and his ilk, will shift in perception. Oliver seems like he’ll remain stuck in time.

His career, most of which was spent with the Pirates, Rangers and Expos, was cut short by the collusion of baseball owners. You can look that up, because Oliver proved it in court. If he played another year or three, he might have gotten the 257 hits he needed to reach 3,000 – a magic number.

How many players with 3,000 hits are not in the Hall of Fame? Just a few. There’s Rose. There are those who are not yet eligible for the ballot (Albert Pujols, Adrian Beltre, Miguel Cabrera, Ichiro Suzuki). And there are those who were linked to PEDs (Alex Rodriguez, Rafael Palmeiro). And that’s it.

Alas, there are no advanced metrics to account for dirty owners colluding to squash free agency, and there will be no justice for AO, the pride of Portsmouth.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Al Oliver deserves more consideration from MLB and Hall of Fame