Why are ‘Dreamers’ who call South Carolina home leaving? ‘It’s like a toxic relationship’

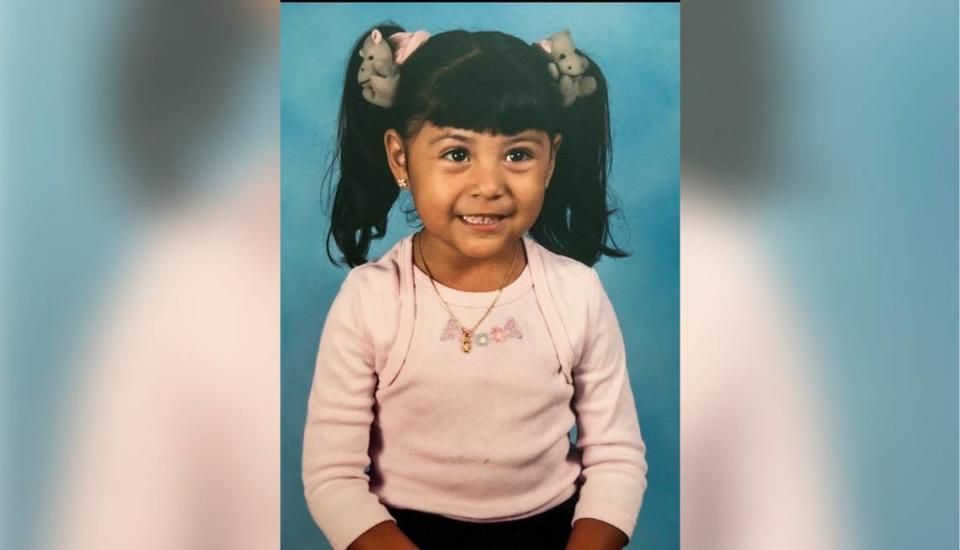

Jackie Mayorga will graduate this year with a master’s degree from one of the country’s best schools of social work. She speaks Spanish and English, and understands a third language, the indigenous tongue of her mother, who was also born in Mexico.

Though she could have her pick of where to go after she finishes her coursework in Massachusetts, Mayorga dreams of eventually returning to South Carolina, where she was raised near Columbia since age 3, to build a community center to help low-income students get into college.

The state needs her badly. In the early 2000s, the Hispanic population grew faster in South Carolina than in any other state. Over the past three decades, it has mushroomed tenfold. Staffing hasn’t kept up. Bilingual job openings in hospitals lay vacant and white teachers outnumber Hispanic ones 40 to 1. The state is projected to be almost 3,000 social workers short by 2030.

But South Carolinians may lose out on Mayorga’s talent, for a few reasons. The first is simple: It’s against the law for her to work as a licensed social worker in the state.

Thousands like Mayorga are barred from more than 100 common careers that require professional or occupational licenses issued by the state. Those include white collar jobs like doctors and architects, but also others like massage therapists and cosmetologists.

Mayorga is one of 5,660 immigrants in the state who are often called “Dreamers.” Each has obtained DACA status from the government — the acronym for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — after submitting extensive documentation to prove they were brought to the United States as young children, have lived in the country since 2012 and don’t pose a risk to public safety. They have no pathway to apply for U.S. citizenship, but are authorized to work and receive social security numbers and driver’s licenses.

They’re “the cream of the crop, as far as undocumented immigrants,” said state Rep. Neal Collins, R-Pickens, who has been advocating for the group in the Legislature.

A bill Collins authored may soon allow “Dreamers” to become licensed practitioners of the majority of the careers they’re currently excluded from. In April, it passed with bipartisan support in the House. If passed in the Senate and signed by Gov. Henry McMaster, the law would change in their favor this year.

Advocates see the legislation as an encouraging sign for the state and the economy, but it would still only begin to ease the challenges DACA recipients face in South Carolina.

Despite the fact that undocumented immigrants pay an estimated $67.8 million in state and local taxes, S.C. laws don’t allow DACA recipients, most of whom were born in Mexico and Central America, to receive in-state tuition in public colleges. They are also ineligible for a piece of the almost $400 million in yearly state-funded scholarships, some of which are paid for by the S.C. Education Lottery, that other high-achieving and needy students are able to secure.

The occupational and educational limitations that DACA recipients face in South Carolina are some of the most restrictive in the nation. But the laws themselves are not the only problem.

An investigation by reporters at The State Media Company and The Island Packet shows DACA recipients reported falling victim to misinformation about the laws while studying at South Carolina’s educational institutions, and said racism was tolerated in the schools they attended. Taken together, the “toxic” climate they described made their situations more difficult than the laws required, they said, and has led to some of them choosing to leave the state.

Reporters spoke to seven of the thousands of S.C. students with DACA status. Though they grew up in the Lowcountry, the Midlands and the Upstate, their stories of mistreatment and misinformation were similar.

‘It followed the stereotype of who they thought I was’

As soon as she learned English in Spartanburg, Alejandra Gonzalez-Rizo was good at it.

So good that in fourth grade, she was recommended for the school district’s gifted program. So good that in sixth grade, when a boy mispronounced a word while reading out loud, she corrected him reflexively.

“Shut up before I call immigration on you,” he told her, as their teacher stood by. “She just went on with the class like that was completely normal,” Gonzalez-Rizo remembered.

She wasn’t so good that she was spared from constantly being made to feel inferior.

All but one of the DACA recipients reporters spoke with mentioned being bullied or singled-out because of their ethnicity. Teachers often failed to punish other kids for making the racist comments, they said, or staff behaved in a racist manner themselves.

By the time Jessica Bonilla Garcia, 27, graduated from Hilton Head Island High School, she was outspoken and popular. She had been crowned homecoming and prom queen and was nominated for the school’s most prestigious student honor. But when she attended Hilton Head Middle, students would command her to be quiet because she didn’t have a green card.

“I’m like, what the hell’s a green card? I’m not taught this,” Garcia said “I remember coming home crying. I’m just in middle school thinking, new year, new start, and this kid’s picking on me because I’m Latina.”

An English teacher who worked at his Charleston area high school told Luis Balderas López, 22, that because he was an immigrant, he would never amount to much.

And when students in her Anderson high school started chanting, “BUILD THE WALL” after former President Donald Trump was elected, Aylin Gomez, now 21, who was born in Mexico, said the teachers took no action.

She and Gonzalez-Rizo recalled that the racism tolerated in the classroom later materialized into something more than a string of hurtful words: It stunted their academic progress. Both said they were discouraged or blocked from taking advanced coursework because of reasons linked to their ethnicity or earlier classification as an English language learner.

“It followed the stereotype of who they thought I was: The Mexican girl with really brown skin that’s dumb,” Gonzalez-Rizo said. “I always hated the fact that they could dictate that narrative for me.”

Misinformation in SC high schools

Though most of the students reporters spoke with said they told their high school guidance counselors about their immigration status, all of them said they were either misinformed at some time or never informed about the financial and professional restrictions that applied to them in South Carolina.

In Charleston, Jessika Motta, 25, had no idea that her guidance counselor would provide information that didn’t apply to her. Her Brazilian parents couldn’t advise her about going to college in America; they didn’t know anything about the process, she said.

“She was the only person that I knew could help me,” Motta said. “And she didn’t have the right tools, or I guess, the right knowledge to help.”

Motta had always been told in schools growing up that she could be whatever she wanted to be, she remembers, and said her guidance counselor told her she’d be eligible for the LIFE and the Lottery Tuition Assistance scholarships. Both grants are set aside for S.C. residents.

A spokesperson from Berkeley County School District did not respond to a request for comment.

By 2030, South Carolina is expected to have one of the most severe nursing shortages in the country, according to the Bureau of Health Workforce. But years after enrolling in her first pre-nursing classes at a local technical college, Motta is not a nurse.

After she started attending classes at Trident Technical College in North Charleston, Jessika Motta finally heard the truth. She couldn’t obtain a nursing license in South Carolina after all. Those scholarships she had been promised? She couldn’t get them either.

And she learned for the first time that students like her must pay out-of-state tuition — and pay it up-front. DACA recipients are barred by law from applying for federal student loans, and from receiving federal grants or the opportunity to participate in work-study programs. For S.C. colleges in the 2020-2021 academic year, the difference between the average in-state and out-of-state tuition and fees was $9,466.

In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court decided a case that likely affected the situation. Justices determined in Plyler v. Doe that states cannot deny students public education based on whether or not they are an immigrant. Doing so would violate the part of the U.S. Constitution that guarantees any person within America’s jurisdiction equal protection of the laws, a majority agreed.

“Because of Plyler v. Doe, school districts can’t, and they shouldn’t, discriminate against undocumented students based on their status,” said Dr. Benjamin Roth, an associate professor at the University of South Carolina’s College of Social Work.

Some schools have responded to the situation by taking the position that they should treat all students the same, indicated Deborah Santiago, the CEO and co-founder of Excelencia in Education, a national nonprofit that advocates for Latino student success.

“It’s inauthentic to say we’re educating all, we don’t distinguish, and therefore everybody is served well, when we know that the strengths and needs of [the Latino] community are more nuanced,” Santiago said. “I think that is in part disingenuous at best — cop out, worst.”

The result of that approach can be that “you get a lot of kids who finished high school without ever having gotten the kind of particular support they need from the guidance department or school social workers,” Roth said.

After Motta switched her major and took a few more classes, she stopped attending. She didn’t have the money to continue. And like many of the students reporters spoke with, Motta reported mentally suffering from the ordeal.

After being promised by guidance counselors a fantasy, and after being raised by their families to value education over almost anything else, DACA recipients told reporters that the shock of finding out the truth about South Carolina’s restrictions made them feel worthless or helpless. One student said he fell into a four-month-long depression after withdrawing from College of Charleston because he couldn’t afford out-of-state tuition. Upon receiving similar news from USC, another student said his depression lasted half a year. During that time, he researched how to kill himself with rat poison.

“To just have that completely taken away from you, it really takes a toll on you,” Motta said. “You consider this place your home, but you’re not welcome. That’s something tricky to get through your mind.”

In one sense, however, she may have been relatively lucky. Someone told her about the rules early in college. For Luis Balderas López and Alejandra Gonzalez-Rizo, ambiguous information about the professional licensure laws they received in South Carolina’s institutes of higher education cost them even more time and money.

Costly confusion about DACA in SC colleges, agencies

In 2014, the S.C. Attorney General’s office addressed a seemingly straightforward question: Would an individual with DACA status be eligible for a S.C. professional or occupational license?

Based on the current law and position of the federal government, “a court will most likely find an individual who has been granted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) status should be denied a professional or occupational license in South Carolina,” the office answered in a letter.

But while attending college, DACA recipients said they were allowed to finish or almost finish courses for professions, only to later be informed that they should change their major or might not be able to sit for a final exam.

The State and The Island Packet confirmed inconsistent information about the laws extends past higher education — state agency representatives told reporters DACA recipients could obtain licenses that the Attorney General’s office, a lawyer and a state lawmaker indicated they couldn’t.

After the S.C. colleges that had promised him money took back their offers, López started building boats instead of going to university. He hoped the effort of manual labor would replace the pain of feeling like the English teacher in high school was right — the one who had predicted he wouldn’t amount to much because he was an immigrant.

But he never forgot his dream of attending college. Armed with savings he managed to collect from working in construction, López started taking EMT classes at Trident Tech. He has spent thousands of dollars to complete the coursework while other students paid nothing, since he’s classified as an out-of-state student. And he finished as the highest performer in the group last year, he said.

López has little yet to show for his efforts but a depleted bank account. Staff at the college informed him in December that his immigration status could mean he might not be able to sit for the national registry exam, the student said, so he would be put on a waitlist to take it as they verified that.

“I already spent my money. I already took my classes,” he said. “I should at least get my money’s worth.”

Trident Tech is aware that having to pay out-of-state tuition is a heavy burden for DACA recipients and it supports efforts to allow “Dreamers” access to more affordable education, said spokesperson David Hansen. As for S.C. laws regarding licensure, because of them, “the college discourages, but does not prohibit, DACA students from enrolling in academic programs that require South Carolina occupational licenses,” Hansen said. Still, “the college is unaware of any prohibition that would keep a nationally registered EMT from working in South Carolina,” he added.

When reporters checked with DHEC, the agency that licenses EMTs in South Carolina, about their understanding of the situation, a representative said something similar: Nothing would prevent a DACA recipient from becoming a certified EMT in South Carolina if they met the requirements.

Though the agency knew of the 2014 Attorney General’s opinion, “we haven’t been presented with a specific situation, to date, requiring further research into and a decision on this question as it pertains to applications for EMT certification, e.g., an application from a DACA recipient, and therefore have not taken a position on it,” a spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, López’s career prospects were paused. Though he said Trident Tech staff informed him later that he would be able to take the exam, he’s still on the waitlist.

“This type of confusion is why we should have a state law making it clear that any immigrant with employment authorization can receive a professional license or certification issued by a S.C. state agency,” said Louise Pocock, an immigration policy attorney at S.C. Appleseed Legal Justice Center, a nonprofit that advocates for low-income South Carolinians.

Gonzalez-Rizo was also informed at the end of her degree program that she couldn’t finish it.

After starting to apply for her S.C. teacher certification in her fourth year of studying education at South Carolina State University, a leader at the education program told her she’d have to change her major, she remembers. The woman had been informed by the S.C. Department of Education in a letter that Gonzalez-Rizo could not be certified as a teacher if she couldn’t get a state license, she said.

“South Carolina State University does its best to meet the needs of a diverse student population while also working within state and federal guidelines,” said Sam Watson, a spokesperson for the college. “The State Department of Education sets standards for teacher certification and awards licenses. Our mission is to provide students with the knowledge and skills necessary to meet those standards.”

Ryan Brown, the chief communications officer for the S.C. Department of Education, told reporters there is currently nothing in the application process that would prevent a DACA recipient from receiving a teaching license.

“That may be the law on the books, but our process does not contemplate that,” he said.

A legal memo written by Pocock explained DACA recipients are prohibited from becoming teachers, since they do not meet the definition of those that are allowed to obtain certifications in South Carolina and state legislation has not yet granted them specific access.

Rep. Neal Collins agreed. “It’s my understanding they cannot,” he wrote to a reporter.

Back in college, Gonzalez-Rizo remembers feeling baffled that a leader of an institution of higher education hadn’t been familiar with the professional licensing laws from the start.

“This is literally what you guys do,” she thought. “How are we still here?”

She paid for an extra semester so she could graduate with a different major. But the ultimate cost might have been paid by S.C. students. Though she is now working as a teacher, she’s serving kids in a private school in Miami, Florida.

She’s not alone. All but one of the seven “Dreamers” reporters spoke to have either already left the state or have considered leaving.

“It was just so toxic,” Gonzalez-Rizo said of her experiences in South Carolina. “It doesn’t matter who you are, it doesn’t matter what you’ve done, it doesn’t matter how big of a dream you have. You’re always going to be boiled down to a DACA recipient.”

Dr. Harris Pastides, the former USC president and a first-generation American, suggested making the process of obtaining degrees and licenses so difficult that DACA recipients choose to live elsewhere should be avoided.

“I do hope we find a path forward,” he said. “Otherwise, these young people will be held up where they will leave. I don’t think that’s what we want as South Carolinians.”

A new bill could help DACA students, SC economy

The S.C. Department of Education knows about the challenges facing DACA students.

Sometimes coordinators of its migrant education program will refer students to neighboring states with more permissive college and career opportunities, agency representatives said.

But the agency also knows it could be doing more to inform the district employees who guide them in schools across South Carolina.

It currently does not train counselors about regulations restricting DACA recipients’ opportunities, said Zach Taylor, the leader of the agency’s Diversity, Inclusion and Access Team. “I think that’s probably a growth area for us,” he added.

While the agency aims to grow, having been moved by DACA recipients who told their stories in the State House, Collins is trying to change the laws. Allowing this group access to licensed professions is a Republican issue, he said.

“I know of no better dream than somebody being here for K-12 experience and wanting to better their lives through more education and through a better job,” he said. “The conservative Republican philosophy is that we want every person to live out their American dream.”

These jobs would become legally accessible to DACA recipients if new SC bill becomes law

This list was compiled using information from https://llr.sc.gov/. It was reviewed by a S.C. Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation representative before publication.

Since most, but not all, licensed professions are included in the bill that passed the House and will be heard by a Senate subcommittee this Thursday morning, Collins plans to draft more bills later. He’s planning one that would grant DACA recipients the ability to obtain licenses in “any other professions that we need,” like teaching. And he hopes to soon be able to suggest granting DACA recipients access to more affordable college education.

The main winner from the new legislation would be the S.C. economy, believes Pocock.

“It’s a huge benefit to our state, because we don’t have enough licensed professionals in several fields,” the attorney said. “This will be a way to address that.”

Mayorga will be watching. As much as she wants to come home, she’s not convinced it will happen.

“Sometimes it’s just like a toxic relationship,” she said over the phone, calling from New England. “South Carolina never wanted me.”