Why Everyone Is So Mad at … the Scholastic Book Fair?

The Scholastic Book Fair, the still-trucking darling of the nostalgic internet, is in trouble. For weeks, librarians have been reporting an odd experience: When they went to order books for this fall’s book fairs, they were given the option to “opt in” to offer books with LGBTQ+ themes and “diverse” storylines. On Reddit almost a month ago, many librarians corroborated a poster’s firsthand report of this phenomenon unfolding at their school. In a series of TikToks from late September, a librarian told the story of being asked to opt in and saying yes. She followed up with a video of an unboxing of all the books that came in that opt-in collection: Lincoln Peirce’s graphic novel Big Nate: Payback Time!, an installment in a series that has previously been dinged for being too “sexual” (“That would sell like hotcakes,” the librarian remarked); Picture Day, by Sarah Sax, another graphic novel in which a middle-school girl asks another girl on a date; Chris “Ludacris” Bridges’ picture book Daddy and Me and the Rhyme to Be; a John Lewis bio; and a Ketanji Brown Jackson bio, because what’s more controversial than that?

After news of the checkbox spread, Scholastic finally issued a press release in response on Friday. The company called the idea that the fairs “put all diverse titles into one optional case” a “misconception.” Instead, Scholastic said, in order to protect “teachers, librarians, and volunteers” who work in states with laws about critical race theory and discussion of LGBTQ+ issues in schools from being “fired, sued, or prosecuted,” it had created an “additional collection”—called “Share Every Story, Celebrate Every Voice”—while maintaining that there are still “diverse titles throughout every book fair, for every age level.”

Though the statement is mealy-mouthed, Scholastic is not inventing a threat here. A teacher in Georgia was fired over the summer after a parent complained about her reading to her fifth-grade class Scott Stuart’s My Shadow Is Purple, a book about gender identity that the teacher says she purchased at the school’s book fair. (The teacher is appealing the termination to the state’s board of education.) Last year, one Texas school canceled its Scholastic book fairs, alleging that two students had purchased “adult” books inappropriate for their age at the fairs in the spring. These cases weren’t mentioned in the press release, but they seem to offer a good example of this kind of risk.

Scholastic, a brand name that doesn’t quite rival Disney but comes close in its particular realm, is a great target for right-wing culture warriors: a beloved purveyor of American children’s content that has long been perceived as a giant of the monoculture. The right-wing publisher Brave Books (“Pro-God, Pro-America children’s books”) ran an anti-Scholastic campaign earlier this year, promoting its own right-wing “book fair” by targeting Scholastic directly. If you put your email address into its website, Brave will send you a PDF with images from specific Scholastic books alongside some pronoun-specifying social media bios and personal photos of Scholastic authors. It mentions that Scholastic’s “largest shareholders include BlackRock and Vanguard” (boogeymen of the populist right) and calls the fair’s books “sick.”

“We all remember the Scholastic Book Fairs of our childhood, with the colorful book displays and the wish-list flyers,” Brave’s anti-Scholastic PDF says. “Scholastic’s iconic Book Fairs have been the primary mode of getting these books into children’s hands.” But the company, Brave warns darkly, is not the same as you remember, and “has had a dramatic shift in its mission and principles.”

On this, people on either side of the political spectrum may now agree. Anti–book banners online thought Friday’s Scholastic press release was far from sufficient, calling the company’s position “craven,” “disgusting,” and “gutless.” “I understand if a librarian needs to separate out certain books because displaying them will put them in danger,” wrote graphic novelist and Scholastic author Molly Knox Ostertag, in a much more understanding response than most. “But I fundamentally don’t think that is a call the publisher should be making for them.”

Scholastic’s down-the-middle response had such a harsh reception in part because its internet audience is made up of bookish people for whom loving the Scholastic Book Fair is a marker of identity and tribe. YouTube is full of Scholastic Book Fair nostalgia videos made by happy nerds who seem to get good viewership simply by remembering how it was. Back in 2017, Vox ran an explainer on the “nostalgic joys of the Scholastic book fair,” citing a since-deleted tweet: “Marry someone who makes you feel the way you felt during scholastic book fair week in grade school.”

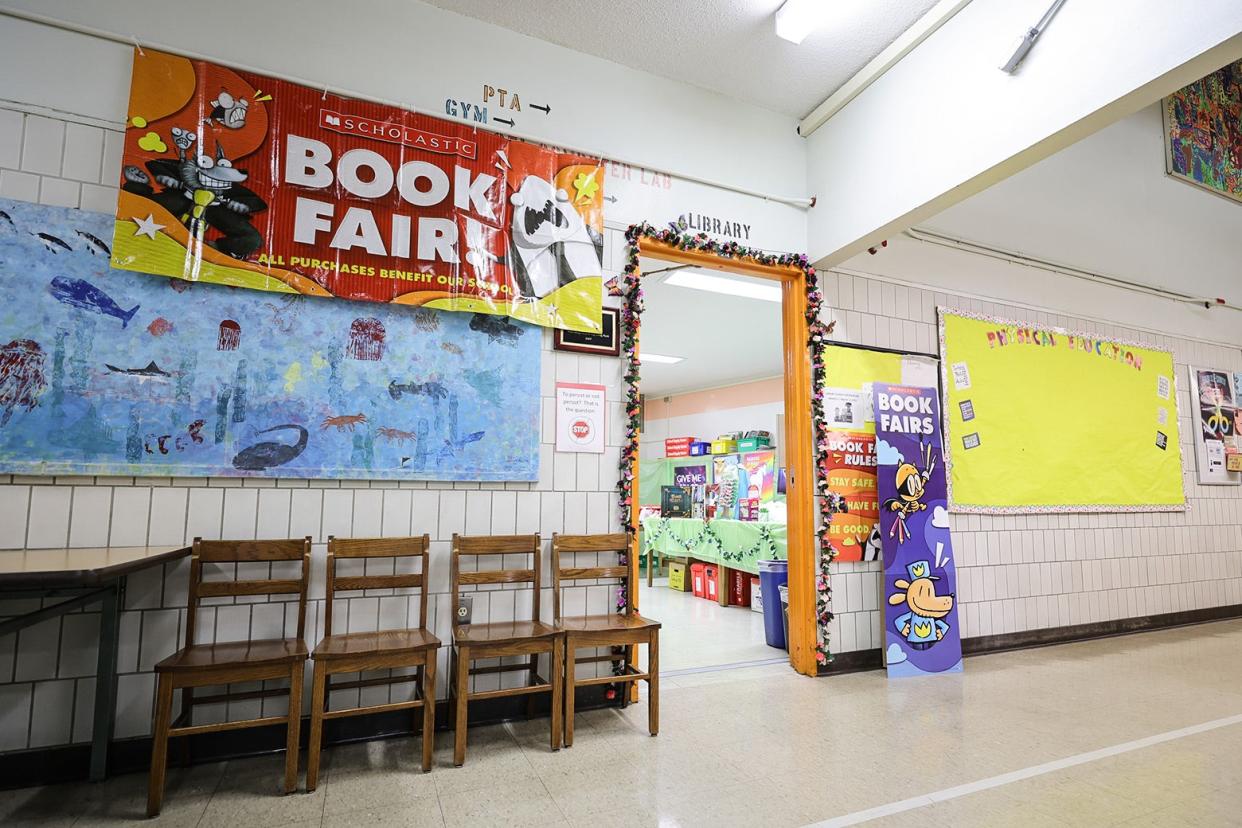

Many of these people, I might gently suggest, have no memory of what a toy store the book fair actually can be. I took a photo of my kindergartner’s book fair “wish list” last spring because it was so amazing. In careful handwriting, the aide who accompanied my 5-year-old around the fair preview filled out the list of “titles” she earmarked for purchase: “1. Mini backpack. 2. Bear highlighter pen. 3. Rainbow bookmark. 4. Jelly fish pen.” The litany of tchotchkes continued onto the back for 20 entries, containing not one single book. (She ended up with a book with a mermaid necklace embedded on the cover.) In other words, the Scholastic Book Fair may be iconic, but for many reasons, it was already far from perfect.

Before Scholastic consolidated the national school book-fair market in the 1990s, there were other choices. Will the politics of the book-banning era provoke an undoing of its chokehold on the category? After author Jacqueline Woodson tweeted about Scholastic’s press release, asking for “other options for book fairs,” many replies mentioned collaborations with local indie bookstores, as well as a startup called Literati. (Literati touts its fairs’ lack of trinkets as a selling point.) But while profits from Scholastic’s book fairs fell, for obvious reasons, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the company says, the business has now recovered. In September, Scholastic CEO Peter Warwick described the spending at Scholastic book fairs as now “very strong.”

On Monday morning, Scholastic’s official account on X posted a meme-ified viral tweet from 2017. Back then, @emsenesac wrote: “U ever smell the air and it smells like the fourth grade scholastic book fair on a chilly Tuesday in October of 2007”? The replies were not positive. “Cowards!” tweeted one. “Go hug a book burner,” added another. The dreaded “opt-in” box may not be the death of the Scholastic Book Fair this time, but it’s clear the company has so far only found a solution that will make no one happy.