Why fixing methane leaks from the oil and gas industry can be a climate game-changer – one that pays for itself

What’s the cheapest, quickest way to reduce climate change without roiling the economy? In the United States, it may be by reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas industry.

Methane is the main component of natural gas, and it can leak anywhere along the supply chain, from the wellhead and processing plant, through pipelines and distribution lines, all the way to the burner of your home’s stove or furnace.

Once it reaches the atmosphere, methane’s super heat-trapping properties render it a major agent of warming. Over 20 years, methane causes 85 times more warming than the same amount of carbon dioxide. But methane doesn’t stay in the atmosphere for long, so stopping methane leaks today can have a fast impact on lowering global temperatures.

That’s one reason governments at the 2022 United Nations climate change conference in Egypt focused on methane as an easy win in the climate battle.

So far, 150 countries, including the United States and most of the big oil producers other than Russia, have pledged to reduce methane emissions from oil and gas by at least 30%. China has not signed but has agreed to reduce emissions. If those pledges are met, the result would be equivalent to eliminating the greenhouse gas emissions from all of the world’s cars, trucks, buses and all two- and three-wheeled vehicles, according to the International Energy Agency.

There’s also another reason for the methane focus, and it makes this strategy more likely to succeed: Stopping methane leaks from the oil and gas industry can largely pay for itself and boost the amount of fuel available.

Capturing methane can pay off

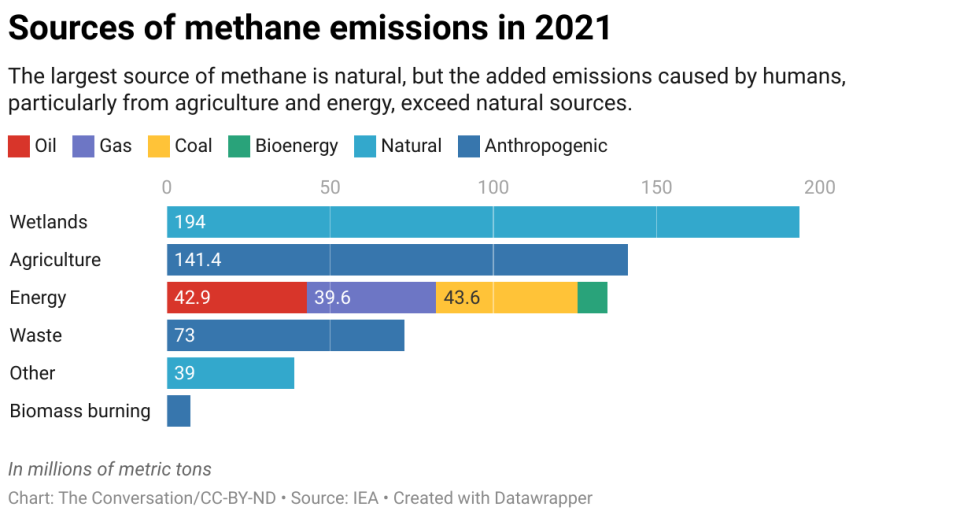

Methane is produced by decaying organic material. Natural sources, such as wetlands, account for roughly 40% of today’s global methane emissions. But the majority comes from human activities, such as farms, landfills and wastewater treatment plants – and fuel production. Oil, gas and coal together make up about a third of global methane emissions.

In all, methane is responsible for almost a third of the 1.2 degrees Celsius (2.2 degrees Fahrenheit) that global temperatures have risen since the industrial era.

Unfortunately, methane emissions are still rising. In 2021, atmospheric levels increased to 1,908 parts per billion, the highest levels in at least 800,000 years. Last year’s increase of 18 parts per billion was the biggest on record.

Among the sources, the oil and gas sector is best equipped to stop emitting because it is already configured to sell any methane it can prevent from leaking.

Methane leaks and “venting” in the oil and gas sector have numerous causes. Unintentional leaks can flow from pneumatic devices, valves, compressors and storage tanks, which often are designed to vent methane when pressures build.

Unlit or inefficient flares are another big source. Some companies routinely burn off excess gas that they can’t easily capture or don’t have the pipeline capacity to transport, but that still releases methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Nearly all of these emissions can be stopped with new components or regulations that prohibit routine flaring.

Making those repairs can pay off. Global oil and gas operations emitted more methane in 2021 than Canada consumed that entire year, according to IEA estimates. If that gas were captured, at current U.S. prices – per million British thermal unit – that wasted methane would fetch around billion. The IEA determined that a one-time investment of billion would eliminate roughly 75% of methane leaks worldwide, along with an even larger amount of gas that is wasted by “flaring” or burning it off at the wellhead.

The repairs and infrastructure investments would not only reduce warming, but they would also generate profits for producers and provide direly needed natural gas to markets undergoing drastic shortages due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Getting companies to cut methane emissions

Motivating U.S. producers to act has been the big hurdle.

The Biden administration is aiming for an 87% reduction in methane emissions below 2005 levels by the end of the decade. To get there, it has reimposed and strengthened U.S. methane rules that were dropped by the Trump administration. These include requiring drillers to find and repair leaks at more than 1 million U.S. well sites.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 further incentivizes methane mitigation, including by levying an emissions tax on large oil and gas producers starting at 0 per ton in 2024, increasing to

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Exactly how many stars are in space? – MeeSong, Brookline, Massachusetts

Look up at the sky on a clear night, and you’ll see thousands of stars – about 6,000 or so.

But that’s only a tiny fraction of all the stars out there. The rest are too far away for us to see them.

The universe, galaxies, stars

Yet astronomers like me have figured out how to estimate the total number of stars in the universe, which is everything that exists.

Scattered throughout the universe are galaxies – clusters of stars, planets, gas and dust bunched together.

Like people, galaxies are diverse. They come in different sizes and shapes.

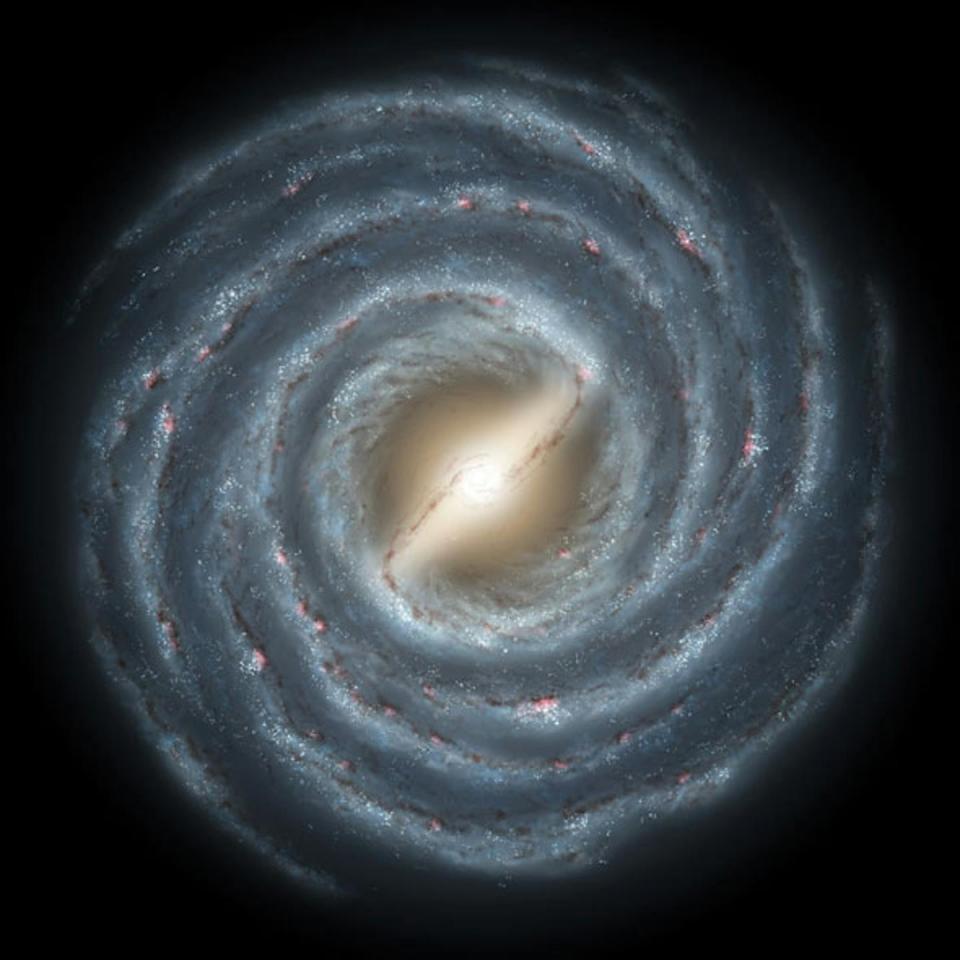

Earth is in the Milky Way, a spiral galaxy; its stars cluster in spiral arms that swirl around the galaxy’s center.

Other galaxies are elliptical – kind of egg-shaped – and some are irregular, with a variety of shapes.

Counting the galaxies

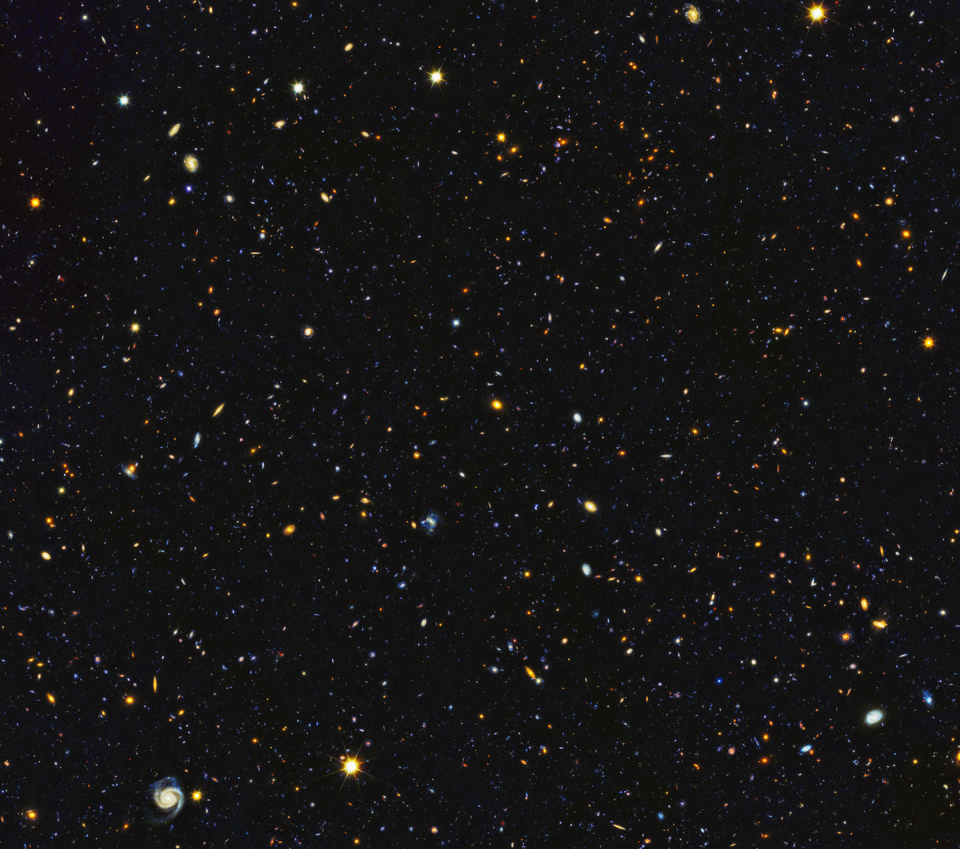

Before calculating the number of stars in the universe, astronomers first have to estimate the number of galaxies.

To do that, they take very detailed pictures of small parts of the sky and count all the galaxies they see in those pictures.

That number is then multiplied by the number of pictures needed to photograph the whole sky.

The answer: There are approximately 2,000,000,000,000 galaxies in the universe – that’s 2 trillion.

Counting the stars

Astronomers don’t know exactly how many stars are in each of those 2 trillion galaxies. Most are so distant, there’s no way to tell precisely.

But we can make a good guess at the number of stars in our own Milky Way. Those stars are diverse, too, and come in a wide variety of sizes and colors.

Our Sun, a white star, is medium-size, medium-weight and medium-hot: 27 million degrees Fahrenheit at its center (15 million degrees Celsius).

Bigger, heavier and hotter stars tend to be blue, like Vega in the constellation Lyra. Smaller, lighter and dimmer stars are usually red, like Proxima Centauri. Except for the Sun, it’s the closest star to us.

An incredible number

Red, white and blue stars give off different amounts of light. By measuring that starlight – specifically, its color and brightness – astronomers can estimate how many stars our galaxy holds.

With that method, they discovered the Milky Way has about 100 billion stars – 100,000,000,000.

Now the next step. Using the Milky Way as our model, we can multiply the number of stars in a typical galaxy (100 billion) by the number of galaxies in the universe (2 trillion).

The answer is an absolutely astounding number. There are approximately 200 billion trillion stars in the universe. Or, to put it another way, 200 sextillion.

That’s 200,000,000,000,000,000,000,000!

The number is so big, it’s hard to imagine. But try this: It’s about 10 times the number of cups of water in all the oceans of Earth.

Think about that the next time you’re looking at the night sky – and then wonder about what might be happening on the trillions of worlds orbiting all those stars.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.If you found it interesting, you could subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

It was written by: Brian Jackson, Boise State University.

Read more:

Brian Jackson receives funding from NASA.