Why flooding from hurricanes in the Wilmington area could get a whole lot worse

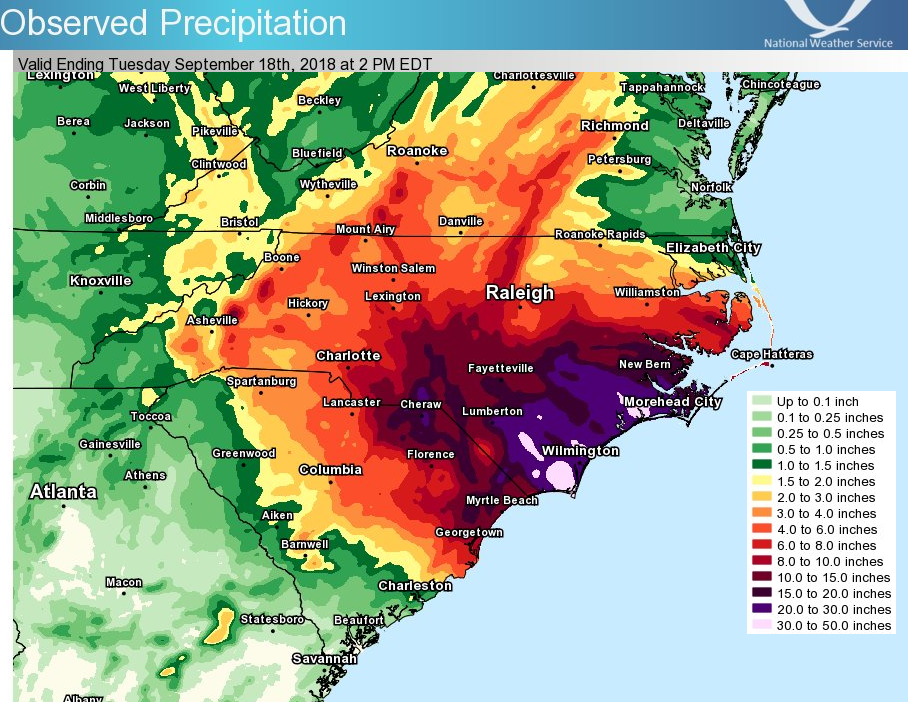

The Cape Fear region is no stranger to flooding associated with tropical weather systems dumping massive amounts of rain on the region. Just in the past six years, Eastern North Carolina has seen two record-setting rainfall events, with Hurricanes Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018 each dumping more than 2 feet of rain − often on the same water-logged areas - and leading to billion-dollar property, public infrastructure and agricultural losses.

But a recent study out of Princeton University finds that hurricane-driven flood hazards in the Wilmington area could dramatically increase in coming decades due to climate change-driven weather changes boosting both the amount of precipitation in inland areas and the dangers from storm surge associated with increased sea-level rise closer to the coast.

SUPER STORMSLearning from Hurricane Ian: Why we should prepare for more storms like it

Avantika Gori, a doctoral student at Princeton, and Dr. Ning Lin, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the university, looked at the interaction between sea-level rise and rainfall runoff to develop a model of what could happen during a massive storm event in the Cape Fear watershed. Using a physics-based storm simulations and new statistical models, the researchers quantified what could happen in certain storm events due to both increased storm surge − driven largely be sea-level rise − and more intense rainfall tied to a warming climate.

"Traditionally, researchers are either looking at one aspect like coastal flooding and damage from storm surge or what's happening inland with the rains," Gori said. "What we wanted to do was look at the combination of the two, because that can make things a lot worse rather than just analyzing one or the other."

The picture they painted wasn't a pretty one.

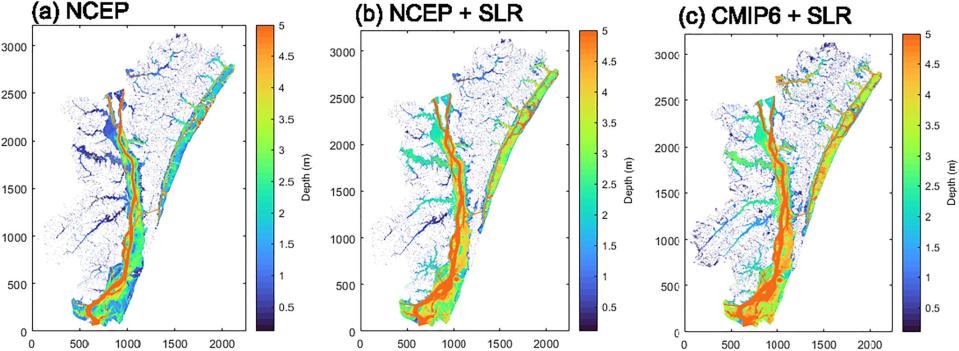

The study, published in late November in the Advancing Earth and Space Science journal (AGU), found that by 2100 the combination of sea-level rise and increased rainfall could lead to a 27% increase in the 100-year flood extent, and a 62% increase in the 100-year flood volume along the Cape Fear Estuary.

Graphics showed areas of Brunswick County, particularly along Town Creek and near the mouth of the Cape Fear, seeing much larger areas inundated by floodwaters. And the sheer amount of water might not be the only concern. Getting the water out, in effect having it drain to the coast, could be an increased problem due to the volume of water being pushed inland due to increase storm surge − not to mention the challenges of levees, berms and raised roadways meant to channel the water toward those exit routes.

"It really was eye-opening to see what could happen," Gori said.

She added that they decided to focus on the Cape Fear watershed because of the recent spate of high-profile hurricane events, starting with Fran, Bertha and Floyd in the 1990s, that have led to major flooding disasters well inland from the coast.

Those natural disasters have been amplified in recent years, with 2018's Hurricane Florence causing a roughly 100-year storm tide in the Cape Fear River while simultaneously dropping rainfall amounts that exceeded the 500-year level.

The Wilmington area hasn't been alone in dealing with hurricanes bringing massive amounts of precipitation to inland areas. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped 40 inches on parts of inland Texas over four days, inundating whole neighborhoods in and around Houston. And just last year Hurricane Ian caused massive flooding in areas of southwestern and central Florida well away from the Gulf Coast, where the Category 4 storm made landfall.

With these recent real-world examples, Gori said it's crucial to jointly model the impacts of storm surge pushing inland and the potentially massive deluges dropped inland when characterizing and preparing for future flood risk potential in coastal areas.

COSTLY DEBATEPlan to assess risk of climate change on insurance, including in NC, courts controversy

"For people and planners at the coast, if you haven't been thinking about the impacts of extreme rainfall on flooding dangers, you better start integrating that into your planning process," she said.

'Could be worse than you think'

Dr. Larry Cahoon is an oceanographer at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

He said that while the Princeton paper does use the worst-case scenario for climate emissions and impacts for the coming decades, the study is on the right track.

"If we don't get a handle on our global warming emissions and continue what we're doing, which isn't that farfetched considering our failures to release overall emissions in recent years and decades, then they want to let people know it could be worse than you think," he said.

Cahoon said climatologists aren't unanimous in whether a warming world will mean more frequent hurricanes. But he said there is general agreement that global warming will lead to more powerful storms, fueled by the warming ocean, and likely slower-moving storms.

More:PHOTOS: Oak Island cleans up damage after Hurricane Isaias

That means tropical systems could not only linger over an area longer, allowing them to dump copious amounts of rain, but could also have more time to push water in front of them onto land, amplifying storm surge impacts at the coast.

Cahoon added that sea-level rise in the Wilmington area could be even greater than those estimates used by the Princeton researchers, which would just aggravate the flooding situation in the Cape Fear estuary.

He noted that the highest readings ever at the Wilmington tide gauge, which sits at the foot of the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge, were recorded during 2020's Hurricane Isaias, a relatively small Category 1 storm that had winds blowing just at the right direction to push the storm surge well up the river into the Port City.

“We’re living in the heart of a place that’s going to experience rapid sea-level rise and likely more powerful storms," Cahoon said. "Like this study, there are some clear warning signs for us that argue for smarter policies so we don't keep putting more people and more homes in harms way.

"The bottom line is we're in a low-lying coastal area, and we know what the trends are."

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Study shows hurricane flooding in Wilmington could get a lot worse