Why this group is building fences to highlight beauty of rolling hills in Wabaunsee County

Every spring and fall, about 15 people get together to build fences out of native limestone in Wabaunsee County.

They also build friendships.

The group has become like a band of brothers and sisters, Chuck Kidd told The Capital-Journal.

What is the Native Stone Scenic Byway?

Kidd is among participants in biannual workshops the Native Stone Scenic Byway Committee has held since 2007 to teach people how to preserve the heritage of the area's historic stone fences.

For three days each spring and fall, Rocky Slaymaker trains participants on how to build and preserve those fences.

They also work at each session on a specific project to create or reinforce a stone fence while stacking the rocks like pieces in a puzzle.

The 75-mile Native Stone Scenic Byway was named in honor of the native stone fences that can be seen along the roadways involved, says the website travelks.com.

The byway's beginning and ending points are 8 miles south of Manhattan, at Interstate 70, exit 313, and at K-4 highway and Glick Road, in western Shawnee County.

In between, the byway passes through communities that include Wabaunsee County's Eskridge, Keene and Alma.

What's the history behind the stone fences?

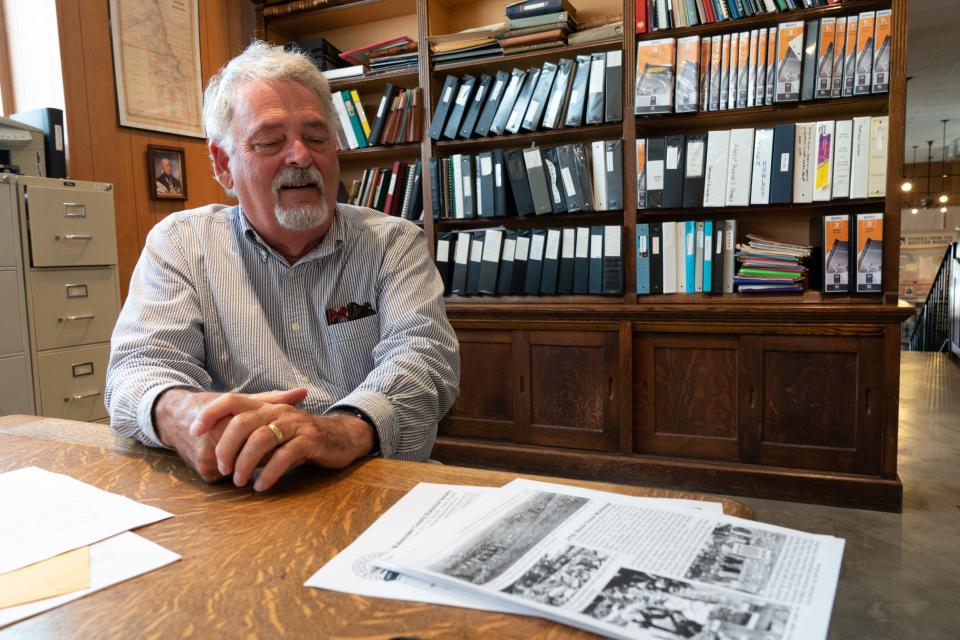

Wabaunsee County is famous for its stone fences, said Michael Stubbs, a board member for the Alma-based Wabaunsee County Historical Society.

The history behind those fences is explained by historical markers standing along the byway on K-99 highway about 8 miles south of Alma — located next to a stone fence constructed by Paul Miller, who has built a lot of those.

Property owners with crops and homesteads built stone fences beginning in the 1860s to keep free-ranging cattle out. Meanwhile, a Kansas state law passed in 1867 provided a payment of 40 cents per rod, or 16.5 feet, to landowners who built and maintained 54-inch-tall stone fences, one of the historical markers said.

"Stone was plentiful and our pioneers built miles of fences," it said.

What has happened to the stone fences?

Many of those stone fences still stand, Miller wrote in an article published last year on the website of the Wabaunsee County Historical Society.

"Others have fallen into disrepair as they are no longer needed, or it was easier to put up a barbed wire fence alongside to keep the cattle contained," he wrote.

A strong desire exists to restore and maintain the many miles of stone fence in Wabaunsee County, Miller added.

"The Wabaunsee County commissioners have passed a resolution to pay anyone who has at least 10 rods of stone fences in good repair a dollar a rod per year for each rod," he wrote.

What's the latest project?

The scenic bylaw committee's latest project involves building a stone fence along the western boundary of Alma City Cemetery, said Marci Spaw, director of the Wabaunsee County Historical Museum.

A stone fence that surrounded the cemetery in the late 1800s was subsequently replaced, she said.

About 70 feet of the new fence was built during the scenic byway committee's last two workshops, which took place in the fall of 2022 and spring of 2023. Miller is providing the stone.

Plans call for 35 to 40 feet more of the stone fence to be built during the next workshop, which is to take place in October, though specific dates haven't been set.

While Alma City Cemetery doesn't stand along the scenic byway, it is a half mile west of that roadway, so the committee hopes to highlight the cemetery's new stone fence as an attraction linked to the byway.

What else is being done in Alma City Cemetery?

Meanwhile, Stubbs said, the Wabaunsee County Historical Society and Mount Mitchell Prairie Guards have been carrying out a project to restore Alma City Cemetery's Potter's Field — where unknown, unclaimed or indigent people are buried — and the cemetery's Section 12, which is predominantly African American.

The project dates back to the spring of 2021, when the late Greg Hoots — a fellow board member for the Wabaunsee County Historical Society who died last year — took on a project to document the heritage of African-American residents in Wabaunsee County, Stubbs said.

After a pasture fire in 2021 west of Auburn City Cemetery, Stubbs said, he and Hoots went onto the property involved with the owner's permission and located several Black homesteads. They found some artifacts and could see where floors and foundations of houses had been, Stubbs said.

After consulting old census records, Stubbs said, "These people came alive."

He identified them as having surnames that included Gardenhire, Davis, Alley and Simpson.

Stubbs then went to Alma City Cemetery to see if he could find where those early homesteaders were buried.

He said his search took him to Section 12, where many graves bore the surnames of the early Black homesteaders.

Section 12 was primary African American not because of segregation but because the families buried there were large and their members occupied most of the available space there, Stubbs said.

Those involved with the project found many graves in Section 12 where headstones were broken, graves had sunk or known gravesites lacked markers, he said.

Led by Bill Roth, of rural Paxico, they subsequently repaired and reset 23 existing headstones and placed headstones on 52 unmarked graves, showed a document they provided The Capital-Journal.

Seeing the names appear on the unmarked graves was "surprisingly moving," Stubbs said.

"These folks were once living, breathing members of our community with their own stories of hardship and endurance," he said. "Bringing their names back is hopefully a first step in discovering their stories."

Contact Tim Hrenchir at threnchir@gannett.com or 785-213-5934.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Group fortifies Wabaunsee County's reputation for quality stone fences