Why what happens in Florida doesn't stay in Florida: What Ian means for NC insurance rates

By the time Hurricane Ian barreled into northeastern South Carolina the afternoon of Sept. 30, making its second landfall on the U.S. mainland, waves fueled by high tide and Ian's storm surge had already overtopped bulkheads in Southport and sent ocean water cascading onto beach town roads from Pleasure Island in New Hanover County to Ocean Isle Beach in Brunswick County. The rising waters also caused Sunset Beach to close the bridge linking the barrier island to the mainland due to overwashing of the causeway.

But a few hours later, the storm and the floodwaters were largely gone. Signs of the weakening hurricane were few and far between in Southeastern North Carolina − largely divided between downed trees and vegetation and isolated power outages. Ian caused similar reports of relatively minor damage in central North Carolina, although it was responsible for five traffic-related fatalities, as the tropical system took a northerly track through South Carolina and North Carolina and into Virginia.

Unlike much of western and central Florida, which were pounded by Ian's record storm surge and rainfall a day earlier, North Carolina saw little impact from the hurricane.

But that doesn't mean the Tar Heel State won't be feeling the financial repercussions of the storm for years to come.

The question is only when, and how much it will hit property owners in their pocketbooks.

Super storms:In a warming world, 'Cat 6' hurricanes could soon be coming to a coast near you

"Indirect impacts will be felt here in North Carolina," said Don Hornstein, an administrative and insurance law expert with the University of North Carolina School of Law. "But the size of them is a little hard to predict."

'Locked in until 2024'

State insurance markets don't operate in a vacuum, but are linked − among other things − through companies that operate in multiple jurisdictions and impacts from the price of reinsurance, insurance for insurance companies to help insulate themselves from the risk of a major run on claims from their policyholders.

When it comes to rates, insurance companies negotiate through their state trade group with the N.C. Department of Insurance. The latest round of talks, which took place this year, saw homeowner rates rise June 1 by an average of 7.9% statewide, with coastal areas seeing an increase of nearly 10%. The N.C. Rate Bureau had been seeking a 24.5% average rate increase.

"That increase is locked in until 2024," said Barry Smith, a spokesman and safety officer with the state insurance department. "Customers won't see any type of increase until after that."

That's when any impacts from damages tied to Ian will likely appear in the rate bureau's proposed new rates, he added.

"But right now it's too early," Smith said of the cost of any property damage North Carolina saw from the recent hurricane. "We just don't know."

Many homeowners are already seeing an increase in their flood insurance rates as the Federal Emergency Management Agency looks to make the National Flood Insurance Program, which provides flood coverage to the vast majority of property owners, a financially viable program instead of one drowning in debt.

But the move to develop a risk-based approach to determining premiums has seen homeowners facing sticker shock when they try to renew their federal flood insurance policies.

Earlier this year the First Street Foundation, a New York-based nonprofit research and technology group, released a report stating that the average flood insurance premium for North Carolina properties within the 100-year flood plain and with a federally backed mortgage, which makes flood insurance mandatory, was $986 a year. That would have to increase by 223% to reflect the true cost of insuring the flood risk those properties face. It would have to nearly double again by 2050 to mitigate the expected higher risks tied to climate change.

Existing in a global market

The massive financial losses expected in Florida from Ian could also drive insurance companies out of business, many of whom could have business in North Carolina. That could shrink the number of insurance sellers, leaving more Tar Heel property owners pursuing policies from fewer companies − a classic supply-and-demand dilemma that could help put upward pressure on rates.

That happened earlier this year to North Carolina customers of Louisiana-based Lighthouse Properties, which closed down in April. The company cited losses tied to 2021's Hurricane Ida, in which it paid out $400 million in damage claims, as a key reason for its demise.

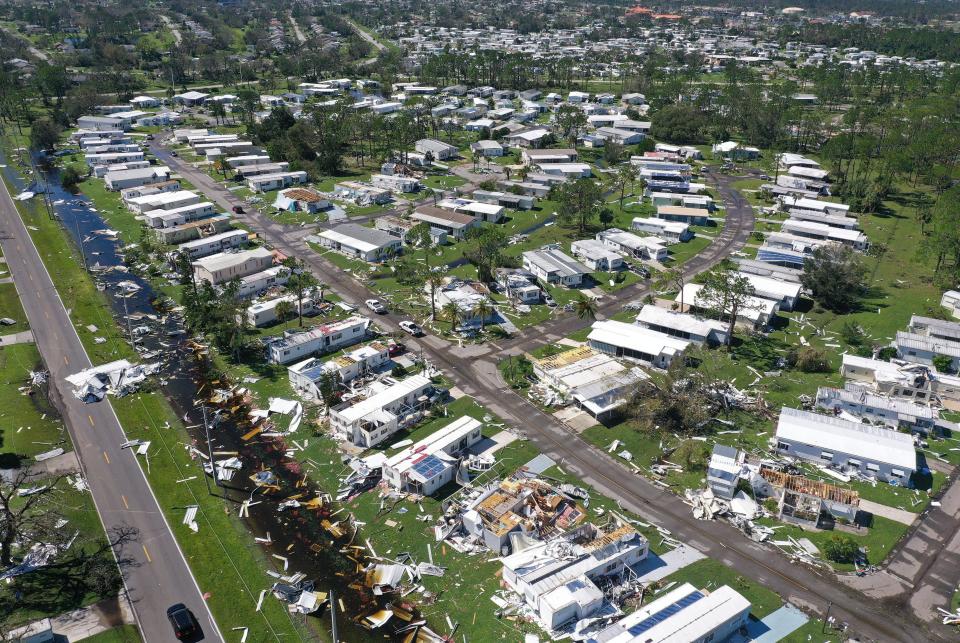

The Insurance Information Institute, an industry-funded research group, estimates that Ian has caused at least $30 billion in damage. That would make it roughly the 12th-costliest U.S. disaster since 1980, according to NOAA records. Some experts think that number could more than double when a final tally is done.

But it might not just be the staggering payouts that hobble these insurance companies. The price of reinsurance, insurance for insurance companies to help them remain solvent after a major claims event, is steadily increasing − assuming it's even available to some companies.

Hornstein, the UNC Law expert, said the reinsurance market operates in a global context, meaning the pooled resources help insurance companies when dealing with payouts tied to the massive flooding in Australia or wildfires in Europe this summer.

But that's a double-edged sword.

“The beauty of reinsurance is it connects us to international financial markets," Hornstein said. "The downside is it connects us to international catastrophes."

He called it a "hardening market," where rates are rising for insurers −10 to 20 percent increases the past few years − as the reinsurance market tightens.

"Ian hit a Florida insurance market that was already teetering on the brink if it hasn't collapsed already," he said, noting that homeowner rates for Floridians are already several times what they are for North Carolinians.

The average property insurance rate in Florida is $4,231 - nearly triple the U.S. average of $1,544, according to the insurance institute. North Carolina's average rate is about $1,700.

Jim Donelon, the insurance commissioner for Louisiana, also has warned that his state faces an insurance crisis as companies, pre-Ian, were already fleeing the Louisiana market after paying out more than $18 billion in claims tied to four hurricanes that hit the state in 2020 and 2021.

Policy black hole:Louisiana insurance crisis could crush home ownership dreams in coastal regions

Talking trees:What ancient trees from New Bern to Wilmington are telling us about future flooding events

Is North Carolina facing a similar crisis?

"We're a much healthier market," Hornstein said.

Giving flood insurance a look

With Ian in the rearview mirror, officials said now is the time for homeowners to review their policies and make sure they have enough and the right kinds of coverage − especially since hurricane season runs through November and climatologists predict storms are only going to get bigger and stronger in the future.

Smith, the spokesman with N.C. Insurance, said property owners should check with their agent annually to make sure they have the right coverage, and the right amount of coverage, to cover any potential losses.

Flood insurance is also a protection many homeowners should look into even if they're not in a flood plain, he added.

“Sure, it might not be required," Smith said. "But if you live where it rains, Commissioner Causey always says it might not be a bad idea to get flood insurance because it's not that expensive if you're not in a flood plain."

Scientists have said they expect climate change to lead to more frequent heavy rainfall events, overwhelming existing drainage systems, even as the actual number of storms is likely to decrease.

Another change tied to Ian might have nothing to do with insurance.

As they do after every devastating storm, officials are expected to look at building codes to make sure they offer the best protection for people and property that could find themselves in a hurricane's path.

Florida did just that after Hurricane Andrew hammered areas south of Miami in 1992, and Hugo prompted a similar review in South Carolina after pounding Charleston in 1989.

“Building codes are your insurance," Hornstein said. "They're your real insurance.”

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Hurricane Ian largely spared NC but could still hit insurance rates