Why Are All the “Healthy” People Drinking Mezcal?

This story is part of the Healthyish 22, the people changing the way we think about wellness. Meet them all here.

Back in 2008, when Yola Jimenez returned to her native Mexico from New York to take over her grandfather’s agave farm, nobody thought mezcal was cool. “It was considered the peasant’s version of tequila,” she says. “No one would give you a penny for it.” But Mexico City was full of energy. Young people like Jimenez were reclaiming their cultural heritage and working to change the city’s reputation as an epicenter of drugs and corruption. “We wanted a different country,” she says, “but no one was going to give it to us.”

So Jimenez took matters into her own hands. She spent her days traveling back and forth from Mexico City to her grandfather's farm in Oaxaca. She learned about mezcal—how it's made, the culture that surrounds it—and got together with some friends to open a mezcaleria called La Clandestina, which became a central hangout for Mexico City's young and creative. It was there that she met Americans Gina Correll Aglietti and Lykke Li (yes, that Lykke Li), and formed the founding trifecta behind Yola Mezcal. From its start, the brand has employed only women, from the farmers to the bottlers, because of a theory Jimenez learned in college: When you pay the women of the family, more money stays within the household. “For me,” she says, “this brand was always about trying to help people from Oaxaca, where I come from.”

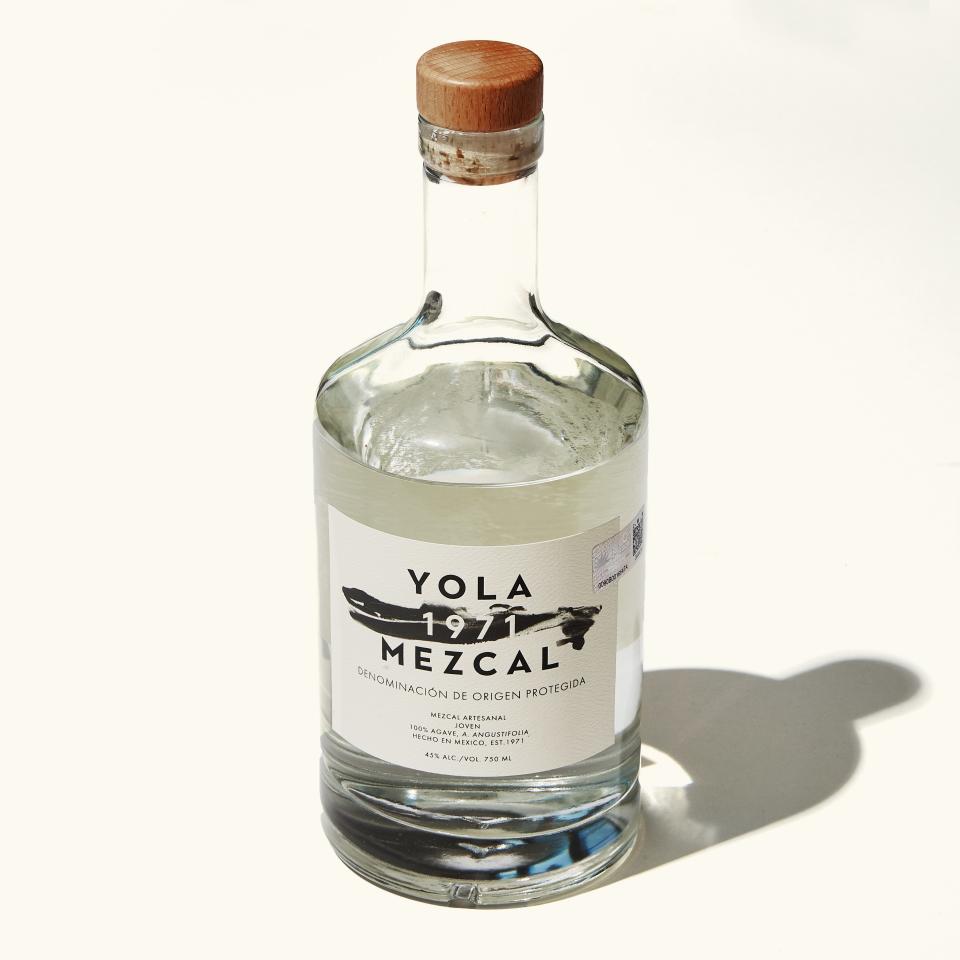

In the years since, mezcal has become the undisputed booze of choice for the wellness-obsessed, with new brands and trendy mezcal bars cropping up from L.A. to NYC. But despite all the hype and buzz, there's still a lot of confusion out there about mezcal: what it is, how it's made, and how to find the good stuff. Here's what we learned from Yola, who still uses her grandfather's recipe from 1971.

Where does mezcal come from?

First, you have to harvest a mature agave plant. Yola Mezcal is made of espadín, the only type of agave besides blue agave (which is what tequila is made out of) that can be farmed. Some wild agaves need to age up to 35 years to be viable for mezcal-making, but espadín requires a minimum of seven years. After cutting the leaves away to reach the inner core or piña, you must bake the piña for three days in a wood-fired, cone-shaped oven dug into the ground and lined with stones. This is what gives mezcal its smoky flavor. Next, you grind the piña in a stone mill—Yola Mezcal still does things the old fashioned way, which means their stone mill is pulled by a real live horse (!) to get all the juices out. After adding water to the juices, you let them naturally ferment in a wooden barrel about two weeks. Now its time to distill the mixture in a copper pot by heating, evaporating, and sending it through a condensing coil two or three times. Once this step is complete, what you have is officially mezcal, but to get the smooth, pure agave flavor true mezcal connoisseurs are after, there's one more step: letting the mezcal age in a glass barrel for three to four weeks. Glass is important because it keeps the flavor clean. And there you have it—mezcal!

Mezcal has blown up in the U.S. over the past couple of years, but it's been in Mexico for hundreds of years, right?

Yes. According to legend, mezcal first came about when a lightning bolt struck an agave plant in the Oaxacan desert, instantly cooking its core and splitting it open. Out poured mezcal, a sacred liquid the ancient Zapotecs believed could help them commune with the gods. Then the Spanish arrived, bringing with them the process of distillation, and mezcal as we know it was born.

Over the years, people in Oaxaca have incorporated mezcal into their spirituality, their medical practices, and their celebrations. For most of its life, the beverage was produced in very small batches by local families; the lack of industrialization and mass production are what keep mezcal special and pure. “A lot of people think it has magical qualities,” say Jimenez. “Sometimes they even give it to babies for teething. I can't speak to the effectiveness of that, but mezcal does give me a certain amount of clarity and vision that I don’t get with other alcohols. I think people are very surprised at how their mind opens, and how they feel the next day.”

I've heard rumors that mezcal doesn't give you a hangover. This can't be true...can it?

Hard science there is not, but we have noticed our post-mezcal mornings are not nearly as bad as some others. Jimenez says this is because good mezcal contains no additives: “Many alcohols have a ton of sugar and other chemicals. My brand has absolutely nothing but organic agave and water. When you wake up after drinking it, you feel the same way as you do when you drink natural wines. Your body just recognizes the difference.” Of course, alcohol of any kind can and will give you a hangover if you drink too much too fast, but that's not how mezcal is meant to be consumed. “People in Oaxaca drink it with a lot of respect,” says Jimenez. “You don’t drink it to get shit-faced. You sip it, you sit with it, you live with it. I think for some people it can change their entire relationship to alcohol, because the experience is so different.”

But is mezcal-mania a good thing? Or are there risks to its newfound popularity?

There are definitely risks. Look at what happened to tequila, which is actually a type of mezcal: Its massive popularity over the past few decades has led to over-harvesting and industrialization. The result? Blue agave shortages and lower-quality product. Tequila today requires only 51 percent agave, and some mass-market brands (as in, the kind most bartenders will serve in a shot glass with a slice of lime and a sprinkle of salt) distill the rest from cheap cane sugar and doctor it up with additives like caramel coloring. Jimenez and others worry that mezcal’s sudden popularity will have a similar impact on the other 30-plus types of agave, some of which take up to 25 years to reach maturity. “It’s going to be the responsibility of brands to grow in a way that makes sense,” says Jimenez. “Never harvest agave too young, and never take shortcuts—but very few are doing that.” Supporting brands like Yola who are making mezcal the right way is crucial to keeping the industry honest and the agave supply steady.

Okay, so where do I find the good stuff?

Well, you could buy a bottle of Yola, cut up some oranges, sprinkle a bit of worm salt, and have yourself a nice little evening. But mezcal is becoming more and more available in bars around the country. Most only carry a few brands, but a growing number of mezcalerias, which specialize in the stuff and boast entire menus of it, are popping up across the continent. Jimenez's bar, La Clandestina, is a must-visit if you're ever in Mexico City. Here in the states, try Clavel in Baltimore, Bar Caló in L.A., The Pastry War in Houston, Todos Santos in Chicago, Ghost Donkey in NYC, or Teote in Portland, OR.

Gimme a great mezcal recipe.

Once you've got your hands on a bottle of Yola (or another good brand) use it in this tart and foamy cocktail from Arley Marks, a friend of Jimenez and owner of Honey's bar in Brooklyn. “I love Yola Mezcal and Amaro Montenegro together,” Marks says. “The soft smokiness and grassiness of the mezcal pairs really well with the depth and bitterness of the amaro. It’s also emblematic of Yola herself and her drive to bring her family recipe from the farms of Oaxaca to far flung places such as New York or L.A. She is a true international figure herself, so pairing flavors from Mexico and Italy just seems to make sense.”