Why my heart breaks for what has become of my beloved Burma

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was my golden wedding anniversary on Feb 2, when I switched on my television, expecting the usual dull, depressing news about coronavirus. But what flashed up on the screen instead was a series of terrifying images from my beautiful home country, Burma (now known by some – though not by me – as Myanmar).

I watched with horror as the military drove trucks through Yangon, the capital city and my old home, ending a decade-long experiment in democracy under the leadership of my old schoolmate Aung San Suu Kyi, who was deposed and placed under house arrest for the second time in her life, for the spurious accusation of illegally importing walkie-talkies.

Standing in my living room in Oxford, more than 5,000 miles away, I became overwhelmed with memories. I thought of my warm childhood, sitting beneath the fruit trees in my grandmother’s garden; and of our family’s hurried and torturous escape. I tried to keep calm, but couldn’t stop the tears.

In the two months since the coup, the south-east Asian country has been plunged once again into violence. Day after day, young protesters line the streets – acts of defiance usually met with brutal retribution from army leaders. On Saturday, the bloodiest day since the coup, the military killed more than 100 at pro-democracy protests across the country, prompting international outrage. Dominic Raab, the Foreign Secretary, described the violence as a “new low”. Those scenes of violence have now come to encapsulate Burma, in the Western consciousness at least. But they couldn’t be more different to my own cocooned childhood.

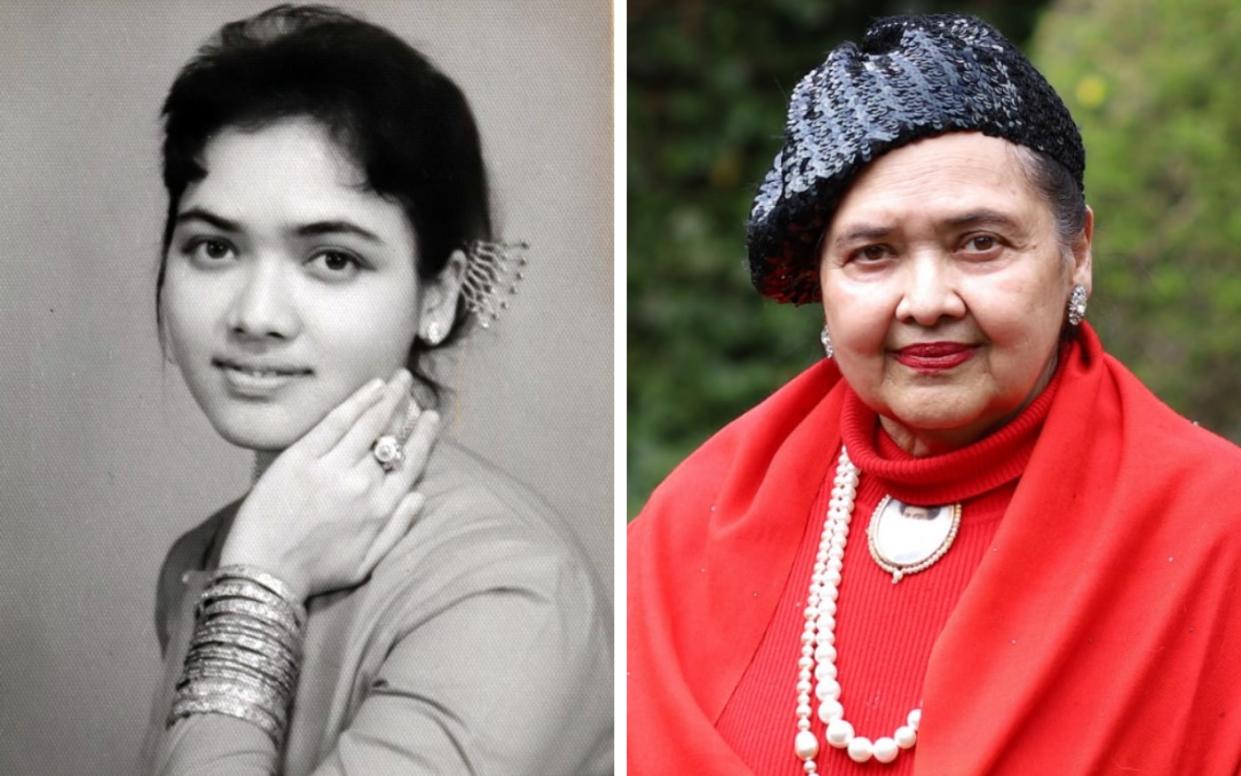

Born in 1949, I was raised during Burma’s “golden era”, part of the first cohort of children with no memory of British rule, although I still learnt English at the English Methodist School, the first choice for the children of the Burmese elite. There, I studied the kings and queens of Great Britain, and read Burmese Days, George Orwell’s unflattering account of life as a colonial soldier in the waning days of the Empire. I was at school with Suu Kyi; I remember her signing up to be a school prefect, telling younger pupils to get into line.

My mother, Daw Aye Myint (baptised Sylvia), was a film producer; we lived in the wealthy Inya area of Yangon, among other educated, internationally-minded families, near the glittering golden pagoda, and near where Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest decades later.

My grandmother ran the largest film studio in Burma, making her one of the richest women in the country, as well as a network of cinemas (the most famous being the Palladium in Rangoon). I always looked forward to the school holidays because it meant more time at grannyma’s home, where the Indian servants brought fresh eggs into the house each morning, and my great-aunts woke before dawn to cook breakfast, using fruit and vegetables bought from the ladies who came house to house carrying trays on their heads.

Later, my grandmother built the whole family a two-storied colonial mansion back in Yangon, which enjoyed an upstairs veranda, where we spent many summer evenings listening to the BBC World Service, overlooking the dragonflies on the Inya Lake, with icy drinks to keep us cool amid the vibrant monsoon heat.

I remember, as a young child, watching my French-English grandfather, sat in his wooden chair, a row of mango trees in front of him and a small table beside him, laden with books. He must then have truly known happiness – as did we all in those long and love-filled days, when the sun seemed to beat down on us from all angles.

That all ended on March 2 1962, when the military launched its first coup, after 14 years of self-governance. We lived near the university, and suddenly heard machine gun fire in the streets. “Something’s gone wrong,” my mother told us, fear in her voice. A servant told us that soldiers were shooting students in the street; my mother ordered us to hide under our beds until the shooting stopped.

After that, life became rather bleak. The country became the Socialist Republic of Myanmar, inspired by the principles of Leninist Russia (some Burmese refugees like me still tend not to use the name “Myanmar”, because we associate it with the military). Our family wealth vanished when my grandmother’s cinema chain was seized by the state, with no compensation. We were given ration books, with measly food allowances – one loaf of bread and two ounces of sugar a week.

Eventually, six years after the coup, the military ordered our family of five to leave Burma. They gave us just one pound each, and subjected us to a painful whole-body search before we were allowed to board the plane. My maternal aunt came to say goodbye on the runway – and, when the guards weren’t looking, swapped handbags with my mother. The bag she gave us contained a stash of family jewellery, which we sold upon arrival in Bangladesh to keep us afloat financially. It was the last time I saw my aunt; we were immensely grateful.

In Bangladesh, I met my husband, the Rev Simon Delves Broughton, a Christian missionary. For several years, I helped him with missionary work, even at one point meeting Mother Theresa of Calcutta. I moved with him to Oxford in 1974; the rest of my family went our separate ways – some to America, some to Australia.

I’m still an immigrant here, but it’s fair to say that I’ve become fully immersed into the British establishment. I studied Theology at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford, and sometimes lecture on Burmese history at St Anthony’s College. I’m heavily involved in my church group at the Oxford Oratory. My son, Philip, attended Eton, where he befriended Jo Johnson, the former Cabinet minister. Philip later went on to write for this newspaper, where he rubbed shoulders with Jo’s older brother, Boris. Jo was even best man at Philip’s wedding.

But still, my heart bleeds for Burma. I returned a decade ago, during its brief interlude of peace. My grandmother’s mansion was covered with overgrown greenery; the windows were broken, and the shutters smashed. The Yangon Palladium – once the crowning jewel of her cinema empire – had been turned into a hotel. Now, it’s not guaranteed I’ll ever get to return.

It was particularly upsetting to read in 2017 about the military’s crackdown on the Rohingya Muslim ethnic minority, which has sent hundreds of thousands fleeing across the border into Bangldesh. Suu Kyi, once a human rights icon, has now faced international criticism for what the UN describes as a refusal to protect the Rohingya. It all chimes so poorly with my memories of such a kind, tranquil land.

One day last year, I was queuing at Oxford’s Ashmolean, when I heard a group of young Burmese men and women chatting away behind me. I turned around and struck up a conversation; they were delighted to hear my stories. I was amazed to see a group of young Burmese travellers enriching their education abroad.

It gave me hope for the country I remember so well from those long, exquisite Burmese days.

East Meets West by Marcia Delves Broughton (£14.99) is out now

As told to Luke Mintz