Why Is Congress Still Meeting in Person?

Brian Baird says that when he was running through the halls of the Longworth House Office Building on the terrifying morning of September 11, 2001, urging people to flee, he thought first about the safety of his family and then about the survival of the United States Congress.

Baird, then 45, was a clinical psychologist and Democrat from Washington State serving his second term in the House of Representatives, sitting in his seventh-floor offices. When the second tower of the World Trade Center was struck by a plane at 9:03, he began to think that people who stayed in those buildings were facing death. He told his staff to keep an eye out the window and came up with a plan. If they saw anything, he and a handful of staffers would spread throughout the building, sounding the alarm. When the Pentagon, on the other side of the river, was struck at 9:37 a.m., they took off down the halls, telling everyone to get out.

“I’m running through evacuating people, thinking about my family and how they were doing, and then saying, ‘What happens if they kill us all?,’” Baird recalls now. Baird says that after he got home that day, he checked on his staff and then set to work on a plan.

In the chaotic months and years that followed—anthrax, the Iraq War, and one terrifying moment when the Capitol emptied after the governor of Kentucky’s plane unexpectedly drifted into Washington airspace—Baird and a handful of allies kept up their quixotic project: Finding a way to keep Congress going in the event of a tragic event, either a terrorist attack or a pandemic.

This was not something he found his senior colleagues wanted to talk about. He recalls bringing it to one veteran Democratic member. “I said, ‘I need to talk to you about something important,’” says Baird. “He said, ‘What’s that?’ I said, ‘You know, we don’t have a valid process for replacing House members if we’re all killed by a terrorist attack.’”

“He said, ‘What do I care? I’ll be dead.’”

Today, the Covid-19 pandemic is reigniting the debate over how Congress continues during times of national crisis. As Americans keep their distance to avoid spreading a new and potentially fatal disease, their elected lawmakers furiously congregate in the middle of Washington, gathering in big rooms, walking narrow corridors, losing sleep. The average age in the House is about 58; in the Senate it’s nearly 63, with some of the top leadership entering their 80s, at extremely high risk from the virus.

The physical concentration of power in Washington seems almost deliberately foolhardy right now: A single point of failure that puts at risk the continued functioning of government, right when the country arguably needs Congress the most.

One senator, Rand Paul of Kentucky, has already tested positive for the virus, as have two House members, Mario Díaz-Balart (R-Fla.) and Ben McAdams (D-Utah). Paul was seen after he was infected—but before he had tested positive—meeting in close settings with fellow members of the Republican caucus, and using the Senate gym and pool.

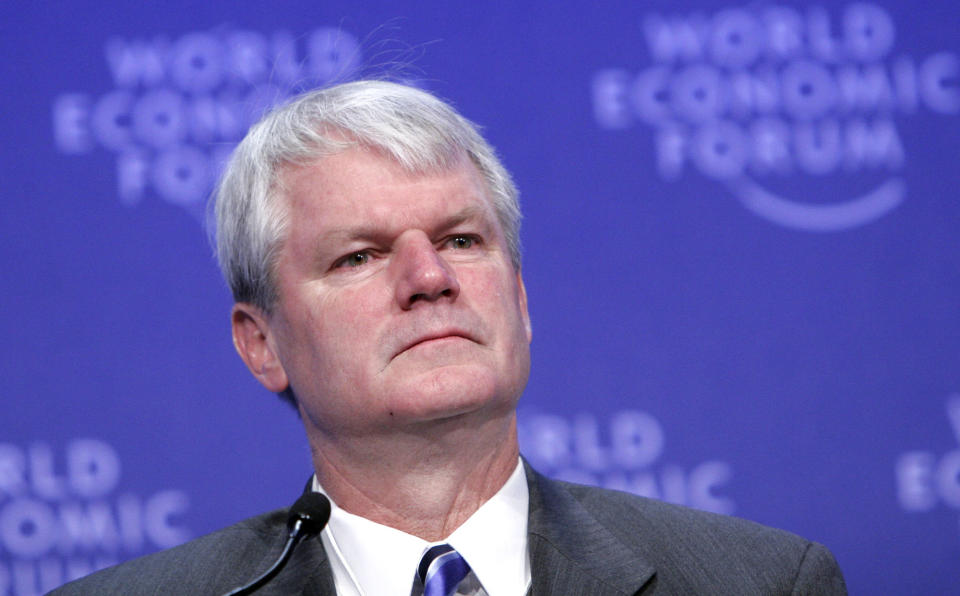

“This is something we should have addressed a long time ago. We got a warning back in 2001,” says Baird, who after leaving Congress in 2011 served as president of Seattle’s Antioch University. But current events are forcing the conversation. “Ask the folks who sat next to Rand Paul if they would have preferred to talk to him online or from 2 feet away.”

But at the same time, the answer isn’t nearly as simple as sending Congress back home to self-isolate, to work remotely and often online, as much of the rest of white-collar America is doing. There’s flurry of talk about remote voting—a step national legislatures in Europe, from Spain to Italy, have wrestled with this week—but voting on laws is just one piece of the puzzle, simply one aspect of what Congress does day in and day out.

And even that, voting, is seen by congressional leadership as a slippery slope. Giving members a taste for working from home, the skeptical thinking goes, could be the first step in a process that ends with a weakened, shriveled deliberative body, one unable to fill its constitutional duty to reach agreements and be a check on the presidency.

John Fortier was the executive director of the Continuity of Government Commission, a bipartisan group that sprang up in the wake of 9/11, convened by the American Enterprise Institute and the Brookings Institution. Former presidents Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford served as honorary co-chairs. The original framers, Fortier points out, designed Congress to be the place where America hashed out its future in person—where the elected representatives of the people gathered to share ideas, deliberate, compromise, build a majority and figure out how to best represent the interests of a diverse country.

“Congress literally does mean ‘coming together,’ and we forget how much of what takes place requires that,” he says. “It’s a much more complex place than just pushing a button one way or another on a roll call vote.”

What should, or could, change? And why hasn’t it happened yet? There are answers to those questions, some of them good, and some of them infuriating obstacles that Baird and others have hit on their way to reform.

In its 231-year history, Congress has proved itself deeply resistant to change. It usually does so only in a crisis. But the country is currently in a state of crisis, one renewing the tough questions about whether, in order to protect itself, Congress may have to find a way to scatter—questions that involve technology, the law and, this being Washington, politics.

One part of the experiment is already underway. Shortly before noon on Tuesday, a group of congressional expats and government experts gathered online for a trial run at conducting the often boring day-to-day business of Congress without being in the same place.

They met via the videoconferencing platform Zoom. From his home office just north of Seattle, Baird “gaveled” the session to order by striking a Buddhist singing bowl.

He then deferred to his co-chair, former Rep. Bob Inglis (R-S.C.), sitting in his home office in the South Carolina town of Travelers Rest, for an opening statement on the topic at hand: a resolution honoring health care workers and first responders on the coronavirus front lines. A witness, Georgetown University’s Lorelei Kelly, weighed in from southwest Kansas, and political science professor Kevin Esterling soon offered an objection from his own home office in Riverside, California. Charles Johnson III, the parliamentarian in the House of Representatives from 1994 to 2004, spoke up on the phone from Bethesda, Maryland, to question whether votes were being properly recorded.

The session was not a runaway success. “It was utter chaos,” Marci Harris, one of the organizers of the Zoom session, says with a laugh. During the 2000s, Harris was a lawyer in the House working on the passage of Obamacare. She’s now CEO of POPVOX, a platform for lawmakers and their constituents to communicate on legislation, and she, along with two other former Hill aides—Georgetown’s Kelly and Daniel Schuman, policy director for progressive advocacy group Demand Progress—organized the session as a volunteer effort to test the remote hearing concept.

There were the usual teleconferencing woes. There were home-schooling background noises, and Johnson’s microphone echoed. But other issues were more specific and became apparent as the exercise played out. How were the participants playing staffers supposed to whisper guidance to the members of Congress they served? What was the best way to offer an amendment? Could the parliamentarian offer real-time feedback to the chair? Were people voting both yea and nay during voice votes, knowing they were off-screen and wouldn’t get caught? What if a member yelled “point of order”—a parliamentary move that can force a crucial stop in proceedings—and the chair simply refused to hit “unmute”?

Still, to a reporter watching from home, it felt a lot like the real-world activity it was meant to simulate: a congressional hearing and bill markup.

Much of what Congress does isn’t so different from any office, and that means it could easily piggyback on the growing suite of tools for telework. The truth is, for all the talk of coming together, much of Congress is already “remote”: Members often pop in and out of hearings and dash from their offices to the House and Senate floors to vote; the staffers in Hill offices already watch floor debates via live video streams. The Zoom platform offers “breakout rooms” akin to the sidebar discussions that take place on the House and Senate floors.

But Congress is not just another workplace: It’s a gathering defined by public accountability, with two centuries of rules and norms that thread back to the Constitution itself. Even the idea of remote voting engenders profound pushback; this week, the Democratic staff of the House Committee on Rules put out a report concluding that remote voting poses serious challenges involving security, transparency, reliability and even mentions in the Constitution to “meeting,” “assembling” and “attendance.” Untested solutions raised worries about everything from foreign interference to the pressure members might face from outsiders while voting in private to the unreliability of communications networks to the difficulties in knowing a member is who he or she says he or she is. And hiccups, the report said, could destabilize trust in Congress.

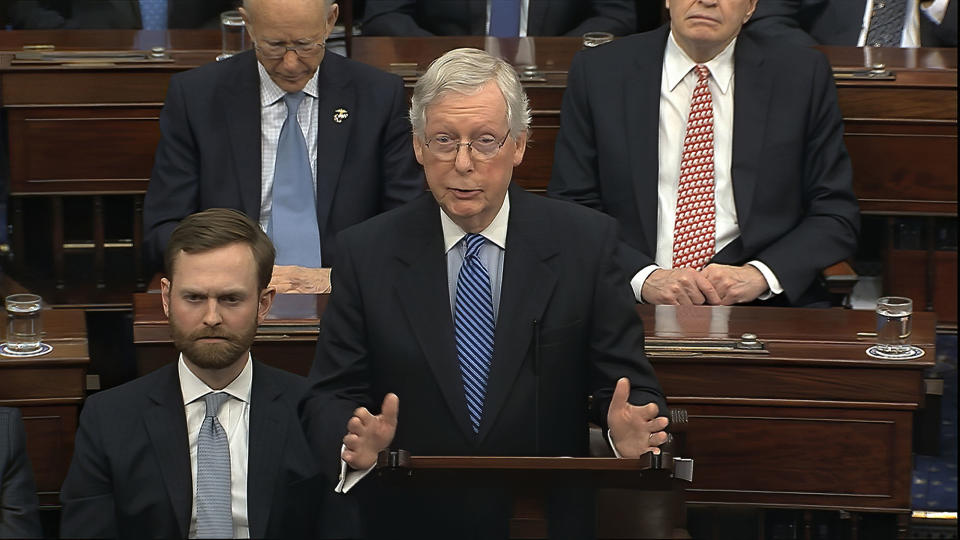

Some advocates say it’s no surprise that it is the rank-and-file members rather than leaders agitating for remote voting, pointing out that they skew younger and are thus arguably more comfortable trusting technology with even enormously consequential tasks. Both Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) have in recent days balked at the idea of remote voting, and the public face in favor of it has become Katie Porter, a 46-year-old first-term Democratic congresswoman from California. (Porter, as it happens, is now self-quarantined and awaiting results of her own Covid-19 test after running a fever.)

One issue is that to go fully virtual, Congress likely couldn’t just adapt an off-the-shelf meeting platform, and the government’s track record of building massive one-off tech systems is uneven, to say the least. Some ideas that have been floated over the years would take a long time to roll out, like a dedicated secure communications network through while members and staff could connect, along the lines of the biometrics-secured system proposed by Rhode Island Democrat Jim Langevin back in 2002. “September 11th and the subsequent anthrax attack on our congressional offices exposed just how vulnerable we are, particularly because we are centrally located,” Langevin said at the time.

A system like that could also carry lasting side benefits, like making it so members of Congress, who largely don’t know one each other, especially across the aisle — Democratic and Republican members are kept separate from the first day of congressional orientation — could communicate safely and, if need be, in private.

Still, there are considerable technical challenges and open questions. What if Russian forces that were so eager to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election turn their attention to congressional hearings? What if trolls Zoom their way into floor debate? How do members of Congress working from their kitchens, living rooms, and home offices get safe access to secure documents?

To Harris, the answer is to learn by doing. “I’m not suggesting we need to hurriedly set up an entirely new process that we think is going to be the Remote Legislative Process from Here to Eternity,” says Harris. “It’s, ‘How do we deal with the current emergency situation with the understanding that there will be lessons learned from that?’”

Covid-19 has already pushed some congressional traditionalists into reconsideration. One of them is Charles Johnson III, the long-time House parliamentarian, who, he recalled after the mock markup wrapped, watched a failed experiment back in the 1990s to test the idea of members from the West Coast voting remotely, instead of having to fly back to Washington.

At a hearing on the topic at the time, as a proof-of-concept, Johnson said, the committee attempted to take witness testimony via conference call. “I had just finished testifying about the sanctity—that was my favorite word—about the chamber and members having to be together, and that remoteness was not a constitutional or proper parliamentary alternative,” said Johnson. “And just then, their sound went off, and so these three members who were communicating remotely could no longer communicate.” The idea, obviously, could never work. “And I just did a quiet ‘hurrah’ when that happened.”

“But,” said Johnson, “that was then.”

The issues, of course, aren’t just technical. Anyone who has spent time around Congress, and especially the Senate, knows that opening up its rules enough to allow videoconferencing would have repercussions that reach deep into how the system works.

Congress is wreathed in rules, and command of its rulebooks gives its leaders an almost mystical power. And when you boil them down, a lot of those rules are built around the ideal that people literally belong in a room together. This isn’t just a quibble: Everyone seriously involved in the continuity debate has grappled with the notion that it would require adjustments to very basic principles, like what’s considered “present,” or what constitutes a quorum.

Over the years, Congress has taken the idea of showing up in physical form seriously. Some of the most dramatic moments in U.S. legislative history—Sen. Bob Packwood in 1988 being carried in feet first to ensure a quorum; 20 years later, Sen. Ted Kennedy, ill with a brain tumor, dramatically returning to vote on health care—were driven purely by physical presence.

But those are also rules the chambers make for themselves, and can unmake, perhaps just for emergencies. McConnell, who has recoiled at the idea of allowing senators to vote remotely, has adjusted how the Senate does business when, in the Kentuckian’s judgment, it benefits the country—such as, to pick one recent example, reducing the time for floor debate on presidential nominees in an effort to accelerate the confirmation of President Donald Trump’s nominees. Norm Ornstein is resident scholar at the right-of-center think tank American Enterprise Institute and a senior counselor to the post-9/11 Continuity in Government Commission. “This is a guy who has blown up every norm and tradition in the Senate,” Ornstein says. “To say he is trying to protect the integrity of the Senate is a heavy lift for me.”

Fortier, former Continuity in Government Commission executive director, does worry about what might be unleashed. If new rules end up loosening the quorum requirements to too great a degree, he warns, you risk ending up with a small, unrepresentative body counting as “Congress.”

Fortier points to the oft-used hypothetical: What if there were a mass casualty event when both chambers of Congress were gathered, putting the ability to pass legislation, declare war and empty the treasury in the hands of whoever happened to not be in the room? “I used to joke, it would be the people who left the State of the Union and went to the bar,” says Fortier, arguing that loosening the rules too much risk putting the fate of the country in the hands of the very few. Emptying Washington on purpose could have much the same effect.

Instead, suggests Fortier, there are other ways to decide what counts as “representative” when members are still alive but simply can’t—for reasons of sickness or family responsibility, or because of travel restrictions—physically be present in Washington. One possibility: proxy voting, says Fortier, in which members hand their vote to someone in the room, and then, maybe, watch online to make sure it is used according to their wishes. “Let’s use the members here, and then build on some things that allow members that aren’t here to be part of the debate,” he says.

Even though Congress tends to see its rules and traditions as long-enshrined, those who have worked on the nitty-gritty of continuity planning for years say they aren’t, and shouldn’t be treated as, black-letter law. Ultimately, Congress sets its own rules—a topic the Supreme Court has also weighed in on, in an 1892 case in which the justices deferred to Congress to determine what counts as passed legislation.

Instead, they argue, the concerns aren’t necessarily about technology, or legalities, but how the move would upend the long-standing order of Washington.

In other words, the issue is ultimately political.

“Leadership thought the precedent of remote voting brought risks of losing Congress,” says Adam Bramwell, who as a Senate staffer was, from 2002 to 2016, a legal adviser to the continuity-of-government boards set up in Congress after 9/11.

Power in Congress is concentrated in the hands of the speaker, the majority leader, the minority leader, and their hand-picked allies–which means that nothing will change until leadership sees it’s in their interest.

It’s possible that distributing Congress around the country would actually put more power into leaders’ hands: If they stay put in D.C. while Congress empties, they end up being the de facto ruling cadre, not having to deal with all the complexities and messiness of dealing with rank-and-file members.

But there are good reasons that leaders wouldn’t want to send their members home if they could avoid it. Having the members of your caucus in Washington—holed up in their offices, passing through the hallways on the way to and from votes—means more chances to use leadership’s leverage to buttonhole them to sponsor a bill, back an amendment, strike a deal. And, some worry, if members like working from home, they’ll simply live in their districts, mailing in their votes, and campaigning nonstop, leaving the institution derelict. Says Fortier: “Arguably you could cocoon in your district.”

And as with everything in Washington these days, the elephant in the room is Trump—who, on Sunday, said of Congress heading home and voting remotely, “I would be in favor of it. I was thinking of it today.” Presumably, that means that if Congress scatters to their home states, Trump stays in Washington and becomes the only story, with the additional Twitter cudgel of mocking them for leaving in a moment of need. (He wouldn’t be the first to try that: In the weeks after 9/11 when an anthrax-laced letter was sent to the Senate, which stayed in session, a New York Post news story mocked the other chamber, writing that “the Republican-led House of Representatives turned tail and ran home.”)

Here, though, argues AEI’s Ornstein, Congress needs to take a step back and realize that acting as a check on Trump is possible only if Congress continues to exist. And that, he says, requires figuring out how to still operate in an institution in times of emergency like the one the country is in now. “The alternative,” says Ornstein, “is to have Donald Trump making decisions without any checks and balances.”

As a conceptual matter, the idea of scattering Congress comes down to how you see the institution’s relationship to the country. Is it a central point where a far-flung nation hashes out its differences, or is it more a reflection of that nation, and could be just as effective in different shapes?

For Demand Progress’ Daniel Schuman, a former attorney with the Congressional Research Service, technology itself offers a useful analogy: The Internet is actually stronger and more resilient for being distributed.

“It’s the fortress vs. the Internet,” says Schuman of the two models of how Congress could work. He points to how the early Internet was inspired, at least in part, by the Cold War desire for a communications system that could withstand Russian missile strikes. “We need to distribute the network so that it doesn’t go down, as opposed to having a single point of failure, where, when it crashes, it crashes hard,” says Schuman.

For Baird, the appropriate symbol is the Roman fasces that sit behind the rostrum on the House floor: A bronze bundle of sticks, held together by a strap, meant to symbolize the strength of states joined together. The togetherness is important, but it’s also a risk. “They’re stronger for breakage” he says. “They’re not safer from fire. If they’re distributed, they’re a lot harder to take down.”

“And,” says Baird, “technology allows us to do that and still be united.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misstated the year Bob Packwood was carried into the Senate Chamber.