Why Jeff Bezos is going to space, and why we should care

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The world’s richest man will hurl himself to the edge of space on a rocket tomorrow morning accompanied by three chosen passengers, on a mission to save the world.

Jeff Bezos has been waiting for this moment since he started Blue Origin in 1999, a few years after minting a fortune by taking his world-changing e-commerce company Amazon public. Blue Origin was intended to address Bezos’ long-seated obsession with humanity’s future in space, which began as a child during NASA’s Apollo years and continued at Princeton, where he was influenced by a theorist of human space habitats, Gerard O’Neill. Bezos thinks that the future of human civilization is moving heavy industry and energy production off of the earth.

It took Blue Origin a long time to evolve from an organization that invited experts to space-themed barbecues to a company that actually developed space hardware. But with the 2015 debut of the New Shepard rocket, Blue’s engineers had a major success on their hands: A vehicle capable of carrying six passengers some 100 km (62 miles) into the sky, but more importantly, one that returns safely to be reused again and again. It was seen as a first step towards bigger things, and an ideal vehicle for luxury tourist flights just out of the atmosphere.

Bezos, and his rival in space business, Elon Musk, both believe the key to doing more beyond earth’s atmosphere is making it cheaper to get there. And both agree building spacecraft that are reusable is the way to do it. The New Shepard won the prestigious Collier Trophy in 2016, recognizing the greatest American aerospace accomplishment that year, after the same vehicle flew five times.

And then nothing happened. While Musk’s SpaceX operates reusable vehicles—the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon crew capsule—that carry US astronauts to the International Space Station, an order of magnitude more difficult than flying them to the edge of space, the New Shepard continued to fly one or twice a year. It carried experiments that needed exposure to a few minutes of near-weightlessness in microgravity, but no people, despite plans to start selling tickets in 2019. Blue Origin refused to say what it was testing, or learning about the vehicle. But two successful flights in January and April this year apparently answered any lingering questions.

“Our plan has always been to go do those…back-to-back flights in what we call a stable configuration,” Bob Smith, Blue Origin’s CEO, said at a pre-flight press briefing. “We had clean flights from both of those, we said we were ready to go, we can fly astronauts.”

What is actually happening?

The New Shepard launch will take place in Van Horn, Texas, about two hours south of El Paso. Blue Origin has built out an extensive test facility there, far from heavily populated areas, as well as the home of its space tourism business. The vehicle is named for Alan Shepard, the first American to reach space in 1961, because it replicates that early, brief visit to the vacuum beyond the planet.

There, the New Shepard will be prepped for launch. The vehicle stands about 60 feet (18 meters) tall, and comprises a rocket booster and a capsule. At 8:30am US eastern time, the four astronauts in the crew will ascend the launch tower and climb into the capsule, strapping themselves into specially-designed seats. That’s the beginning and end of their activity; as Smith puts it, “this is an autonomous vehicle, there is really nothing that a crew member can go do.” Outside of regulations aimed at protecting the public from a rocket explosion, there are no government rules for space tourism safety.

At 9am, the New Shepard’s rocket engine will ignite, burning a mixture of liquid hydrogen and oxygen for nearly two minutes. The rocket will accelerate past the speed of sound.

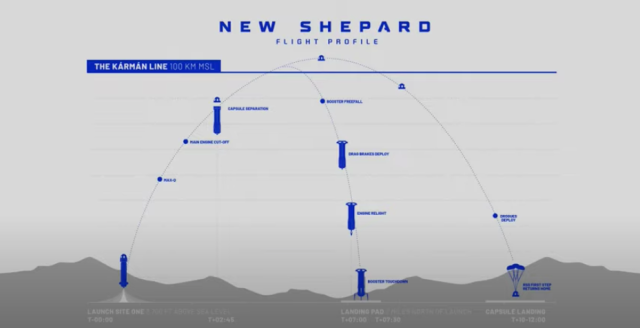

As the vehicle nears the 100 km peak of its trajectory, the capsule will separate from the booster below. The booster then flies back to the launch site to land vertically, like a spacecraft from a science fiction movie. The capsule will continue on a parabolic trajectory, hanging in space for a few minutes. At that point, the passengers will experience microgravity and be able to unstrap from their seats and float around for a few minutes, watching the planet below for the first time. Then, they’ll need to buckle back in before the capsule descends, using parachutes and, seconds before touchdown, small thrusters to provide a soft landing in the Texas desert.

The experience will only take about 11 minutes.

The New Shepard’s mission profile.

Another suborbital space company, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, pulled a similar stunt last week: Its vehicle, a rocketplane that is air launched from the bottom of a jetliner, also shoots up to the edge of space before gliding back to land on earth. Blue Origin’s executives argue that their experience is better in part because Virgin Galactic’s plane can only reach an altitude of 53.5 miles (86 km), about 10 miles lower than the New Shepard. Both altitudes are recognized as being the border of the atmosphere with space by different organizations; from a physical sciences point of view, recent research suggests that 80 km (50 miles) is the most accurate line to draw.

Who is the rest of the crew?

You’re probably familiar with Bezos himself. The Amazon billionaire, owner of the Washington Post newspaper and philanthropist is just thrilled to be here, realizing the dreams he had when he was five years old, watching the Apollo astronauts land on the moon. (This, by the way, is the 52nd anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission.)

The first passenger announced by Blue Origin is Bezos’ younger brother, Mark, an advertising executive and volunteer firefighter. Bezos asked his bro to join him on the mission in an emotional Instagram post. It certainly underscores the confidence that Blue Origin has in the safety of its vehicle.

The second passenger announced is the 82 year-old Wally Funk, a life-long aviator who at the dawn of the space program participated in a program aimed to prove that women could meet the same rigorous tests as male NASA astronauts. While the women were abled to match their official counterparts, NASA wouldn’t fly a female astronaut until 1983. Bezos invited Funk to join their crew and finally reach space, becoming the oldest person to do so in the process.

Finally, Blue Origin launched a month-long auction process to find the first paying passenger for the vehicle. That process resulted in $28 million winning bid, with the proceeds going to Blue-sponsored aerospace charities. But the winning bidder, whose identity remains undisclosed, backed out at the last moment over a schedule conflict, according to Blue Origin spokespeople. Instead, the runner-up for the auction, an 18 year-old Dutch student named Oliver Daemen, the son of hedge fund investor Joes Daemen, will take the seat and become the youngest person to go to space.

While it’s hard to believe Blue’s tale about a scheduling conflict, the sudden change did force the company to be more transparent about its auction. It said some 7,500 people participated, and confirmed that it had originally scheduled Daemen for the second flight expected no earlier than late September.

“What a brilliant story it provides for us,” Ariane Cornell, Blue’s director of astronaut sales, said this week. “Wally Funk, who will become the oldest person to ever fly to space at the age 82, and Oliver, the youngest person to ever fly to space at the age of 18.”

Is space tourism going to change the world?

The backlash to space tourism at these prices is already visible in the media, which shouldn’t surprise anyone: Space exploration is always a hard sell compared to problems on earth, and adding in the ultra-wealthy and their luxury hobbies makes an easy environment for hot takes.

From Blue’s point of view, luxury has always preceded mass access to any transportation project. That’s been true in particular of automobiles and aviation. “Entertainment turns out to be the driver of technologies that then become very practical and utilitarian for other things,” Bezos said in 2017. “Even in the early days of aviation, one of the first uses of the very first planes was barnstorming, they would go around and land in farmer’s fields and sell tickets.”

You’ll note that barnstorming isn’t big business today, and no one is sure how deep the market for space tourism of this nature will be. If there is sufficient interest and competition with Virgin Galactic, it’s possible to imagine prices falling to the point where mere high-income professionals could access these experiences instead of the dynastically wealthy. But you could also see this becoming a mere novelty compared to billionaires who pay for real voyages into space, like the trips being sold by the company Axiom Space onboard SpaceX’s Dragon space capsule.

Operating the New Shepard could help evangelize space experiences, but there is a more pragmatic analogy offered by Bezos: “The GPUs that are now used for machine learning and deep learning, they were really invented by Nvidia for video games…and so the entertainment industry can often be a driver of technology that then gets repurposed.”

Whether or not space tourism is a booming business, Bezos believes it is a key first step to developing technology that can achieve his bigger ambitions beyond the planet.

What else is Blue Origin doing?

For Blue, the New Shepard has always been a test-bed. The software and aerodynamic controls to make the New Shepard reusable have been scaled up for the New Glenn, a much larger orbital rocket the company is developing to compete with SpaceX in launching satellites and astronauts.

Perhaps most important has been the development of Blue’s BE-3 rocket engine. The rocket engine is always the most expensive and difficult design part of a space vehicle, because it is where the fundamental problem of going to space gets solved: Engineers need to contain and direct an enormous amount of force in order to break free of gravity. Making that engine reusable and reliable is no easy task, either.

Now, Blue has taken those learnings to create new engines, for the New Glenn and for the company’s proposed lunar lander to carry NASA astronauts. While New Shepard has largely been funded by Bezos’ fortune, the US government has chipped in to contribute to the development of those new vehicles because it can imagine buying them for its own purposes. Blue Origin’s engine will also power a new rocket Lockheed Martin and Boeing have designed for the US military.

For Bezos, this has always been a long game. Blue Origin is named for the planet Earth, which Bezos views as “the best planet” and in need of protection. He argues that in the long-term future of humanity, people will have to seek energy from beyond the planet in order for civilization to avoid stagnation. “The Earth is no longer big,” Bezos said in 2019. “Humanity is big.”

For Bezos, this is a vision for his great-grandchildren to enact. He sees his job as a seeding a new industry in the mold of the internet age that shaped him, where space entrepreneurs can innovate without the capital of a government agency or mega-contractor behind them. In his eyes, the first crewed flight on the New Shepard is just one small step towards a much larger leap.

Space cowboy.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz:

The face of global luxury brands in China is at the heart of a #MeToo storm

Novavax’s effort to vaccinate the world, from zero to not quite warp speed