Why The Latest FCC Net Neutrality Plan Is Meaningless

Directly after a vote by the five heads of the Federal Communications Commission on May 15, a news alert popped up on my unregulated mobile device (an iPhone) saying, "FCC approves new rules for Net neutrality." That's not true. In fact, the FCC did virtually nothing other than let each of its five commissioners give a speech about why the Internet should be open and non-discriminatory, and then hand the issue over to the American public to sort out.

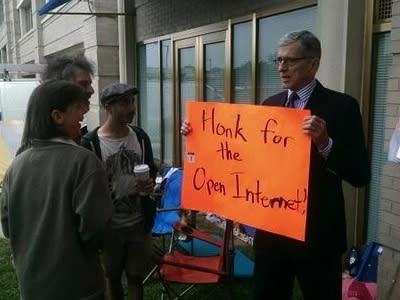

Multiple times during the meeting and in the weeks before, FCC Commissioner Tom Wheeler called the document presented today a proposal. All the vote did was make the document public so people could criticize it. Furthermore, Wheeler backed away from his own proposal, which doesn't call for changing the legal means of regulating ISPs, by continually saying that "all options are on the table."

MORE: What Is Net Neutrality: FAQ

No matter what happens, the whole Net neutrality debate has so far been about nuanced legal interpretations rather than open discussions about the role of the Internet in modern life and the best way to protect that openness.

There are two reasons why the latest vote achieved nothing: First, most of the draft plan is unenforceable because it's based on a legal interpretation that was struck down twice in prominent cases, the last just this year in January. Second, it doesn't address the one proven way the FCC could regulate ISPs to insure they don't discriminate against content providers ranging from Netflix to makers of YouTube cat videos.

What are Section 706 and Title II?

The May 15 meeting kept referencing two little-known pieces of legal jargon, without anyone explaining what they are: Section 706 and Title 2. These two items from the Telecommunications Act are at the heart of the question facing the FCC: whether the agency can ever make and enforce rules to prevent ISPs from controlling what information people get, and how they get it, on the Internet.

So far, Section 706 has been the basis for the FCC's Net neutrality policies, last spelled out in the Open Internet Order of 2010. On first reading, Section 706 looks like a solid grounding. But in two huge cases, one brought by Comcast and one by Verizon, the FCC's reasoning was shot down. Section 6 requires the FCC to make sure that the Internet is as fair and accessible as possible, to promote the economy and the public good. This is the money quote:

"The commission … shall encourage the deployment on a reasonable and timely basis of advanced telecommunications capability to all Americans … by utilizing, in a manner consistent with the public interest, convenience and necessity, price cap regulation, regulatory forbearance, measures that promote competition in the local telecommunications market or other regulating methods that remove barriers to infrastructure investment."

The FCC's reasoning is that insuring an Internet that is most useful to citizens is the best way to grow this technology industry. The Washington, D.C., Appeals Court in the recent Verizon case agreed with how the FCC interpreted Section 706. In its Jan. 14 ruling, the court wrote, "Does the Commission's current understanding of section 706(a) as a grant of regulatory authority represent a reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute? We believe it does."

Title II and the "common carrier" roadblock

So why did the D.C. court strike down the Open Internet Order? Because, as clear as Section 706 is, it doesn't jibe with another part of the Telecommunications Act called Title II, which trumps anything else. (The court did let some of the lesser parts of the Open Internet Order stand, however, such as a requirement that ISPs report how they manage their networks.)

MORE: The Case Against Time Warner-Comcast Just Got Stronger

Ironically, the FCC caused this legal conflict in the first place by deciding not to classify ISPs as something known as a "common carrier."

To understand this nuance, you have to go way back to the original Communications Act of 1934 (the 1996 law is technically just a set of amendments). That act defines a type of company called a common carrier as, among other things, "any person engaged as a common carrier for hire, in interstate or foreign communication by wire or radio." (Under U.S. law, a company is a person.)

Title II of the 1934 law then provides sweeping regulatory control over common carriers in Sec 202 (a):

"It shall be unlawful for any common carrier to make any unjust or unreasonable discrimination in charges, practices, classifications, regulations, facilities or services for or in connection with like communication service, directly or indirectly, by any means or device, or to make or give any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular person, class of persons or locality, or to subject any particular person, class of persons or locality to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage."

That's exactly the authorization the FCC needs. A common carrier can't discriminate against the parties it serves or what they deliver, and this goes for any means or device. In other words, it's future-proof for new technologies that have developed. The law also prevents giving preference to any party, which would cover, for example, a telecom company favoring its own online video service over Netflix or Amazon. The words "undue or unreasonable" might worry some Net neutrality advocates who fear the FCC would bend to political pressure, but it could also be encouraging to skeptics of government regulation that the FCC can't be too meddlesome.

Just one problem: The FCC decided way back in 1980 that, while transmitting voice calls is a common carrier activity, transmitting data is not. In terms of that day's tech, the FCC can protect your right to service when you talk on the phone, but not when you hook your modem up to it. As broadband emerged, cable companies took on the role of ISPs, and the FCC never designated them as common carriers. As wireless grew, the FCC explicitly ruled that wireless data providers are not common carriers.

So those sweeping powers under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934 — they don't apply to the Internet. And without those powers, the FCC has, by its own volition, opted out of regulating ISPs, so say two huge court cases.

Title II or bust

Given all that, it seems impossible for the FCC to impose its Net neutrality rules without designating ISPs as common carriers. Technically, there's nothing to stop the FCC from doing so. But politically, it would be a nightmare — which, Wheeler has hinted, is why he's trying to pass new regulations without going that route. Adding regulatory authority goes against current conservative doctrine. House Speaker John Boehner and the House Republican leadership just issued a letter to Tom Wheeler on May 14 praising the growth of the Internet economy and warning that "efforts to regulate the Internet as a utility under Title II are threatening to set back this progress."

MORE: How to Watch Live TV Online

The most conservative of the FCC's five commissioners, Michael O'Reilly, said essentially the same thing during the hearing, before he and fellow conservative Ajit Pai voted against the proposed rules.

The Title II route will be a hard one for all sides in the Net neutrality debate. But it's the only route that leads to a conclusion where the FCC can enforce real Net neutrality.

Follow Sean Captain @seancaptain and on Google+. Follow us @tomsguide, on Facebook and on Google+.

Copyright 2014 Toms Guides , a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.