Why are we so in love with the Second World War? The reason is simple...

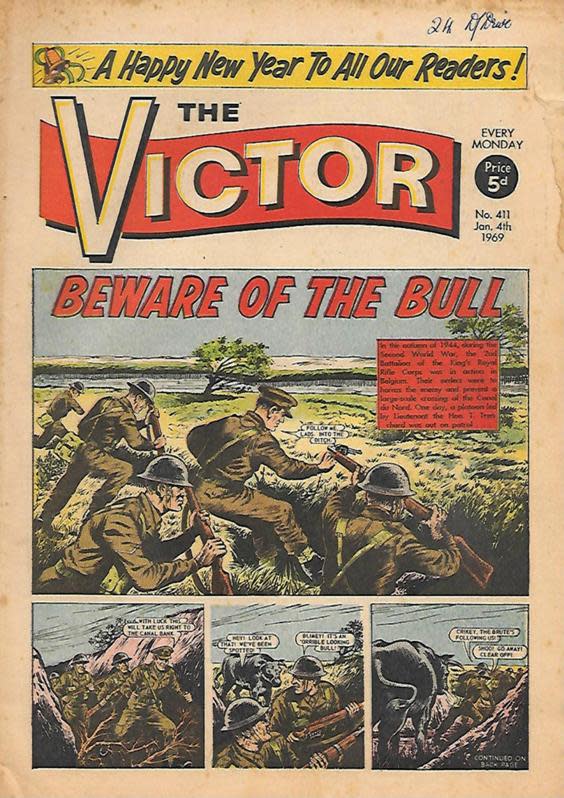

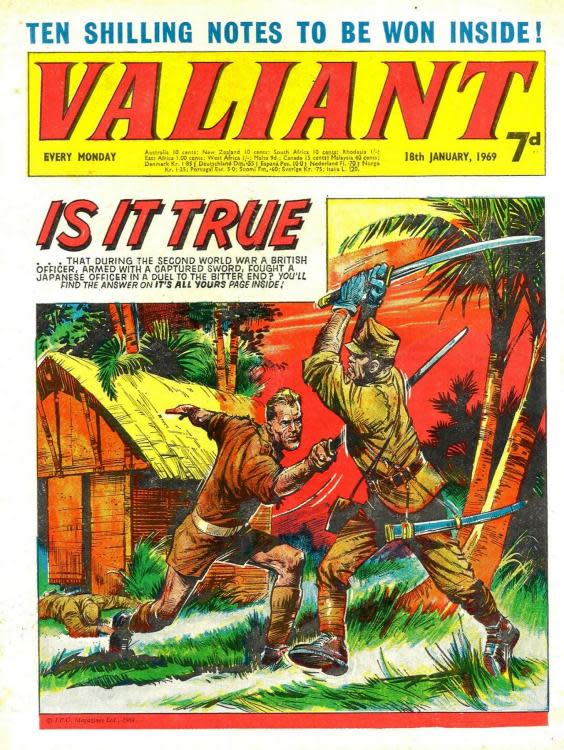

In January 1969, Geoff Dyer, aged 10 and a half, and studying for his 11-plus exam, went to see Where Eagles Dare at the ABC in Cheltenham with his mum and dad. He had been too young for the Summer of Love, but he was just the right age for the Winter of War. He had already roughly tossed aside Beatrix Potter and Enid Blyton in favour of The Victor and The Valiant, boys’ comics full of tales of derring-do in the Second World War.

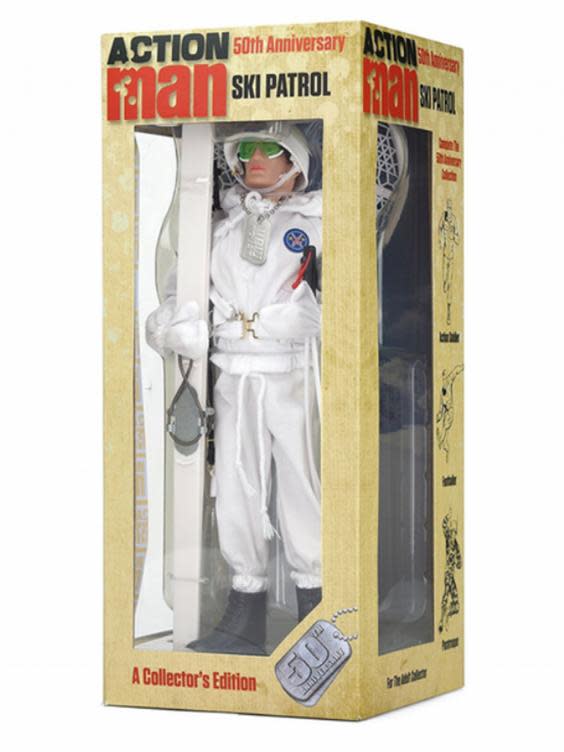

He had found an advert in one issue for a Luger, and had sent off for it, and it was his favourite toy (although made out of metal, it was, after all, only a toy gun). He also loved his Action Man figure (with dedicated ski patrol outfit) and his Airfix models of the Lancaster bomber and the American B-17 “Flying Fortress”.

He was the perfect audience. Where Eagles Dare (director Brian G Hutton, starring Richard Burton, Clint Eastwood and Mary Ure) completely bewitched and bedazzled the young Dyer. From the opening shots of a Junkers Ju-52, camouflaged, flying over snow-clad Bavarian mountains, to the strains of a quintessentially Second World War soundtrack (composed by Ron Goodwin), he was convinced: this was what war was (or should be) like. Roguish and ruthless heroes pitting their wits against the might of the Third Reich.

The boy Dyer grew up, became a moody student, studied English at Oxford, and would hang out at small, Gauloises-scented cinemas on the Left Bank in Paris watching Eric Rohmer films of a Tuesday afternoon. He went on to become a standout critic and novelist, writing weird and wonderful, semi-unclassifiable works about jazz (But Beautiful), the Venice Biennale (Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi) and the Tarkovsky masterpiece Stalker (Zona – “a book about a film about a journey to a room”).

When he was appointed guest director of the Telluride Film Festival in 2013 he came up with a personal pick of five films. All of which resided securely on the cultural high ground represented by, for example, Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. And definitely did not include a Boys’ Own-style Second World War action film so brilliant and yet so absurd that it’s verging on Carry On Up the Cable Car. He probably didn’t mention The Victor or The Valiant when it came to discussing his favourite reading either. But after Telluride he thought to himself: “How could I not have picked Where Eagles Dare?”

He felt bad about it. Ashamed of his own sense of shame. And he knew he really had to go public about it his guilty secret. So he has outed himself, in the shape of his recently published Broadsword Calling Danny Boy, a meta-book of the movie, an exegesis tracing and reconstructing the film on the page, scene by scene, in one flowing, lyrical love song. And this month the BFI is showing Where Eagles Dare on its 50th anniversary. Which raises the question – what is it about this film that makes it of enduring value? What is the source of, in Dyer’s words, its “obdurate power and ageless magic”?

Its legion of fans includes Steven Spielberg and Quentin Tarantino. When the producer Elliott Kastner read the script, he immediately cabled Alistair MacLean to say: “Best screenplay I have ever read stop adjectives useless to express my love of what you have created stop.” But the still more important question is, why are we still in love with the Second World War? And, OK, one more: is this prolonged love affair really doing us any favours?

In one way, Where Eagles Dare is entirely of its era. Dyer shrewdly points out that the very name of General Carnaby (who is captured by the Germans, thus triggering a rescue mission) is an allusion to Carnaby Street, fashion mecca and probably the most famous British street of the Swinging Sixties. In the summer of 1966, when the film was first conceived, England beat West Germany 4-2 in the final of the World Cup (even if there was debate as to whether the ball had crossed the line).

Where Eagles Dare replays that victory, with England spanking the Germans all over again, but this time 89 (Germans killed, according to a modest YouTube estimate – it feels like more) to nil (Brits/Americans – unless you’re a treacherous double agent and therefore secretly playing for Germany all along). The Germans are firing those magic bullets that Clive James has referred to, the kind that go around the actors with star billing instead of through them.

The function of Nazis now becomes clear. In an inversion of the Holocaust, their role is simply to be massacred. But it seems as if there are always more of them, an inexhaustible supply of targets. Like fairground soldiers (or ducks), they are always popping up again, waiting to be shot or stabbed or blown to pieces.

The chief assassin in the film is Clint Eastwood who, as laconic as ever, has imported his skills from the spaghetti westerns of the period. Dyer draws attention to one particularly nasty piece of hand-to-hand killing where Eastwood shoves a knife through the neck of a Nazi traffic warden while clamping one hand over his mouth to stifle the cries.

The plot may be mind-blowing, but the one outstanding mystery in the film is surely linguistic. All the Brits and the one American “can speak fluent German” we are told and duly pass themselves off as Nazi officers. But how is it that we can understand them without the need for subtitles? Why is it that German sounds suspiciously like English? The Germans likewise speak decent English, albeit with pronounced German accents. There is a barely an achtung! or a schnell! Implicitly, perhaps, we can hear the line beloved of the WWII nostalgia comics of the time: “Der Engländer kommt!” (usually followed shortly afterwards by “aaaagh!”

In a sense, this is all simply cinematic magic, and we must suspend disbelief. Tarantino, for one, won’t allow it though and in Inglourious Basterds insists on his German-speaking British spies really speaking German, being queried on their accent, and unleashing gunplay if they dare to get any subtle nuance slightly wrong.

But the whole point of Where Eagles Dare – and here we touch upon what Dyer calls “the essence of greatness” – is that, despite the war between nations, it is ludicrously easy for a German to pass himself off as a Brit and vice versa. And for English to pass itself off as German. Ja! For the subtle secret conveyed in this film – made more explicit in the recent television series, The Man in the High Castle (based on the book by Philip K Dick) – is that practically anyone, with only minimal training, can be a Nazi.

Dyer references The Nazis, a brilliant book of photographs collected by Piotr Uklanski, bringing together all those actors who, at one time or another, have dressed up as Nazis, sporting swastikas and death’s heads and iron crosses. Actors get a special pass on what would otherwise (as in the case of Prince Harry) be either frowned upon or ruled strictly illegal. They get to strut and make the Nazi salute and snap, “Heil Hitler!” and similar.

The greatest ever Nazi, to my way of thinking, is none other than Derren Nesbitt, who plays the Gestapo officer, Sturmbannführer von Hapen. The way he purses his lips is totally Nazi. The way he slaps his leather gloves against one hand is totally Nazi. His curly blond hair is 100 per cent Nazi. He appears twice in The Nazis.

And yet Derren Nesbitt is, of course, English. Born in London. Now living in Sussex (aged 83). He actually sought out an old Gestapo officer in the quest for authenticity. But the reality is it’s easy to be a Nazi (which may partly explain why we so readily reach for the word these days – as per protestors outside parliament, and even “grammar Nazis”). “Naziness” is not historically and geographically specific; it’s a permanent potential built into the human condition. We are forever teetering on (or over) the brink of becoming Nazi. Major Smith (Burton) is also, very plausibly, Major Schmidt.

This interchangeability of Nazi and non-Nazi is precisely what lies at the core of the labyrinthine plot. If Brits can so easily pass themselves off as Germans, then clearly Germans can pass themselves off as Brits and thus infiltrate the British intelligence organisation. By the same token – and here we come to the sustained central scene in the Great Hall of the Schloss Adler in which all secrets are revealed and a large number of Germans killed – it is conceivable British agents might well be trying to sneak into the German high command by the back door, and launch a plot to assassinate Hitler (a line taken up by Tarantino). As Eastwood/Lieutenant Schaffer says: “Right now, Major, you got me about as confused as I ever want to be.”

I called up Dyer in Los Angeles, where he teaches creative writing at the University of Southern California, in search of further clarification. He is excited that the film is being shown at the BFI. “It’s a pity they can’t parachute me in for the screening,” he says, inevitably seeing himself in terms of his movie heroes. He’s seen it (as I have) about 50 times and he still goes back to it. “There’s not a dull moment,” he says. “It’s the least boring film ever made.” Where Eagles Dare omits boredom. Everything in it is an adventure. It still speaks to the 10-year-old in all of us, whether you’re boy or girl. This is war as fun.

And this, I think, explains why we remain so dangerously in love with the Second World War. Well, you may say, why wouldn’t we be? Didn’t we win? How can that be wrong? But almost everything we think we know about the Second World War is, if not wrong, at least seriously ambiguous. In the we won line, for example, who is we, exactly?

The peculiarly British problem is that we tend to think in terms of Spitfires and Dunkirk and Churchill. It was won by “the few”. No, it wasn’t. It was won by there being more of us (when you add it all up, including Russians and Americans and Indians and Nepalese and so on) than there were of them. In other words, the exact opposite of Where Eagles Dare. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that the title of the film takes a Shakespeare line (from Richard III) and simply omits the not (“The world is grown so bad, that wrens makes prey where eagles dare not perch”),

Dyer has another book out this month, Life with a Capital L, in which he has edited and introduced a collection of nonfiction works by DH Lawrence. Dyer’s prose is as supple and sensual and colloquial as Lawrence’s, only much funnier. As he says over the phone: “There is a higher ratio of gag lines in Broadsword Calling Danny Boy than in my other books.” Consider this footnote, for example, talking about the seeming “impregnable” fortress that is the Schloss Adler: “By the time I was 12 the idea of the impregnable had been so thoroughly impregnated by notions of pregnability that to describe a place as impregnable was to suggest its extreme vulnerability to infiltration and attack.”

Our default mode, in Second World War films, is Commando or Action Man. The SAS was born in this period (arising out of similar outfits like the SOE, Special Operations Executive). The title of the popular television series SAS: Who Dares Wins not only quotes the regimental motto, but feels like a homage to Where Eagles Dare too.

“There were one or two films shortly after the war,” says Dyer, “with John Mills looking stoical and getting wet on the bridge of a ship.” But then “reality receded”. A whole slew of films, such as The Guns of Navarone, The Heroes of Telemark and 633 Squadron, some of them also written by Alistair MacLean, took over. Even when we gave up national service, we were increasingly steeped in the cultural reproduction of war.

The idea, now lodged forever in our brains, is that the Second World War was one big adventure. Or a series of small adventures stuck together, end to end. Being parachuted in “behind enemy lines” (the lines seemed to exist only so you could get behind them) translated brilliantly on to the silver screen. Conversely, the action movie imprinted itself on our filmically attuned collective unconscious. History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as film, and finally as dream.

As a result, we are walking around with a fantasy of the Second World War in our heads, a hyppereal version of history, in which Nazis will always bite the dust. Even more neorealist revisions, such as Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (those Nazi bullets really can go through you after all, even underwater) and Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, have done little to shake that conviction. Rebekah Brooks’ security guys, for instance, used the “Broadsword calling Danny Boy” line while covering up News of the World phone hacking data.

Our imaginary, hyperbolic, semi-miraculous “history” has undoubtedly infiltrated, if not German high command, certainly our current politics. As Dyer, cheerfully anachronistic, notes, “the getaway is an allegory of Brexit”. But it is also true that Brexit is an allegory and encapsulation of our fantasy Second World War with the European Commission taking the place of the Third Reich. We go in, then we get out again, having slaughtered as many of the enemy as possible.

One of the ironies of the film that Geoff Dyer draws attention to is that, despite everything, we are still in love with German technology. Where Eagles Dare is a surreptitious homage to “Vorsprung durch Technik”, to the Junkers plane, to the Schmeisser machine gun (Lt Schaffer’s weapon of choice), and above all to the Luger. Somehow Derren Nesbitt and all the other faux-Nazis have got their mitts on a 10-year-old boy’s favourite toy.

Geoff Dyer’s ‘Broadsword Calling Danny Boy’ and ‘Life with a Capital L’ are published by Penguin. ‘Where Eagles Dare’ is showing at the BFI in London on Saturday 26 January at 7pm

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’. He teaches at the University of Cambridge