Why are so many Black patients dying from heart failure?

Heart failure stubbornly remains a leading cause of death in this country. Moreover, our own failures to do something about it are disproportionately impacting the Black community. In fact, ZIP code matters substantially more than genetic code in determining health outcomes. Black patients are dying from heart failure at considerably higher rates than white patients.

This should set off alarm bells, but sadly that has not been the case. We need to deploy available resources, public and private, to address not just the heart failure epidemic gripping our nation, but also the unparalleled and unjustifiable health inequities for our most vulnerable.

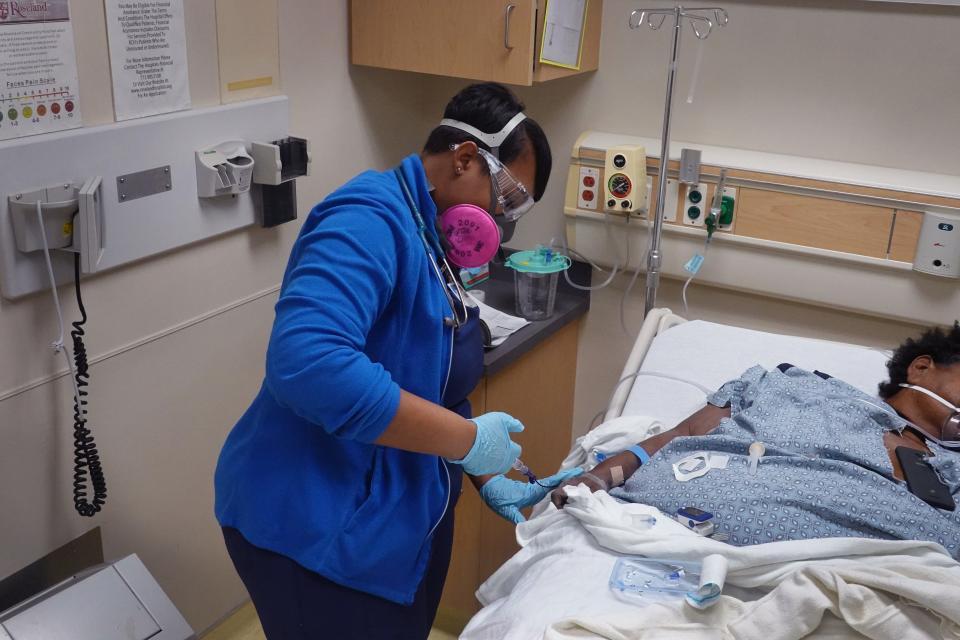

The problem unsurprisingly stems from a long history of systematic racism and the poverty it has caused. Accessing quality medical care is much harder for many Black patients. Clinics are too frequently located far from their homes and taking off time from work, finding child care and arranging transportation all contribute to the many challenges Black patients face before they even arrive at a point of care.

Opinions in your inbox: Get exclusive access to columnists and the best of columns

Barriers to care for Black patients

Once there, Black patients are less likely to be treated by a cardiologist, which can result in cases going undetected and poorer outcomes for patients. Health care costs are at the center of why many Black patients do not pursue medical care. A large number may be without insurance or lack sufficient coverage to pay for hospitalization.

Medicines remain expensive, and there are too few resources available to support those unable to afford proper treatment. In cases where financial assistance does exist, patients and doctors might be unaware of the options or find themselves mired in daunting application processes.

Perhaps even more shocking are the lives lost due to insufficient knowledge. We see that a lack of access to adequate, authoritative medical experts and information about heart failure remains a major contributor to the very high prevalence of heart disease in the Black community.

Can you die from a broken heart?: How emotional distress can wreck your body

Is our transplant network working? Dozens of Americans die daily waiting for an organ transplant. Why do we let this happen?

There are quite simply not enough resources and experts able to connect to those at highest risk. It has also led to lower levels of participation in clinical trials for potential new treatments and fewer Black heart failure specialists, community cardiologists and medical science researchers.

We are awakening to a new dawn however, one on which industry must now join forces with health care providers to elaborate on patient engagement.

There is a desperate need for new public awareness initiatives about the disease that are created by and focused on the Black community. We have to create a more robust pipeline of Black medical and research talent, which can overcome a historical mistrust of the medical community stemming from past abuses, as well as more diversity in clinical trial enrollment.

However, enhanced education and awareness are insufficient if not also coupled with greater access as measured in reach, frequency, affordability and equitable treatments.

Health care's 'valley of death'

Pharmaceutical companies can help by providing financial bridges for uninsured and underinsured patients, and help cover the cost of medicines during the often lengthy gap between a drug’s Food and Drug Administration approval and Medicare coverage – a span the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services describes as “the valley of death.”

No one should die because of bureaucratic delays, nor should intermediates like pharmacy benefit managers remain cloaked behind transparencies and their role in excessive drug costs.

I lost my son to fentanyl: America desperately needs new medical treatments

Public health: We can agree that no one in this country should go hungry. Can that help unite America?

The bottom line in heart failure is both measured in dollars and deaths. Racial inequality of this magnitude demands a large-scale government response. The heart failure epidemic in America needs to be declared a national public health emergency.

The absence of heart failure – and even more glaring, heart disease, as the No. 1 cause of death in this country – from President Joe Biden’s "moonshot" initiative – which includes cancer, diabetes and Alzheimer’s – is inexplicable given the toll heart failure is having on American families across the board and in particular the Black community.

We need to dedicate more federal research funding to developing new treatments for this massive burden on our nation’s health care system.

Developing and delivering new medicines that improve patient outcomes is essential but takes time. However, we can no longer be patient in addressing long standing racial inequities facing patients who are Black men and women struggling with heart failure.

We must also be triaging and treating the underlying afflictions to our health care systems with sufficient speed and scale to ensure all patients receive the treatments they deserve.

We need a national call to action initiative to identify care service programs that incentivize providers to expand into these areas, as well as initiatives to overcome social determinants to health care. Our Department of Health and Human Services must explore public education campaigns on heart failure reaching and resonating with the Black community, similar to those used effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

Heart failure is itself an epidemic, and the fact that it so disproportionately impacts Black patients is a national tragedy. We must see rapid, robust public and private efforts invested in saving these lives.

The credibility, efficacy and equality of our health system depends on what we do at this moment.

Dr. Alanna Morris is an associate professor of Medicine at Emory University. Robert Blum is the Henry Crown Fellow at the Aspen Institute and CEO of Cytokinetics.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black patients are more likely to die of heart failure. Why?