Why was the mob in L.A. so much quieter than in Chicago or New York?

Quick, now: When you think of bootleggers, blackmailers, gunsels and hoodlums in natty double-breasted topcoats, what city comes to mind?

Chicago, probably. New York, maybe. Detroit, possibly.

But surely not Los Angeles. Organized crime, in the place that liked to preen that it was the simon-pure “white spot” of America?

Pull up a chair, kids.

L.A.’s mobsters were few in number, and maybe they were wearing board shorts under those topcoats — yes, I joke — but organized crime rackets and L.A. go way back together, and also way up, from City Hall and the LAPD, and down to speakeasys, vice dens, gambling joints and brothels.

Our sunshine racketeers weren’t Capone-grade, but Al Capone did come to town a couple of times. The first time, in December 1927, he was a guest at the Biltmore Hotel for a day or two before his incognito was blown and the cops hustled him back on a train to Chicago. “I thought you liked tourists!” he complained to The Times then. “Who ever heard of anybody being run out of Los Angeles that had money?” The second time, in 1939, he stayed for about 10 months — as a guest of the federal prison hospital on Terminal Island.

From the years before Prohibition until well after the Second World War and even into the Disco Decade — when “gangs” had come to mean drug and street gangs — organized crime ran a full-service range of criminality: kickbacks, loan sharking, extortion, payoffs, shakedowns.

And did civic L.A. mount a white horse to drive them out? As if.

In the 1920s and beyond, L.A. mobsters found themselves in vigorous criminal competition with the graft operations being run boldly out of the mayor’s office and parts of the LAPD. There were times when Angelenos must have wondered whether the police “vice squad” was for vice or against it.

L.A.’s criminal backstory gets mugshot-detailed scrutiny in a new book, “Los Angeles Underworld,” a kind of illustrated scrapbook of organized crime and its civic cousin. Its central figure is Jack Dragna, a man The Times once said was “perhaps the only classic ‘godfather’ that the city has ever known.” It’s written by Avi Bash and J. Michael Niotta — Dragna’s great-grandson.

L.A. had far fewer Italians than did New York, but Sicilians like Dragna “came out West because either they were on the lam, or because they were ranchers or farmers as they had been back in Sicily,” Niotta told me. “The climate in Southern California was very similar to Sicily. And before Prohibition, I wouldn’t say it was an organization so much as maybe local criminals and loose confederations. Prohibition is what gave them a reason to organize and come together.”

If they were going to keep the money coming in, they had to come together to deal with another mob called “the Combination,” “the Spring Street clique” — officials who used the authority of City Hall to profit from the same criminal delights that enriched the mob, sometimes working in competition, sometimes hand in glove.

Joe Domanick, an authority on the LAPD’s history, described it in The Times: “The LAPD’s central vice squad was on the take; and a loose, organized-crime syndicate was protected by the top aide of Mayor George Cryer. It wasn’t violent, big-time, high-profile, Chicago-style organized crime. But its corrupting influence was just as real.”

In the next decade, Mayor Frank Shaw ratcheted up the racket. He scammed city projects and contracts, and his brother sold the answers to LAPD hiring exams to candidates he favored. The long-gone magazine Liberty wrote in 1940 that in the 20 years before Shaw was recalled, in 1938, “the city of Los Angeles had been, almost uninterruptedly, run by an underworld government invisible to the average citizen.”

When the mob wasn’t competing with City Hall profiteers, it was paying them off. A 1937 grand jury minority report by some city reformers made it plain: “[A] portion of the underworld profits have been used in financing campaigns [of] . . . city and county officials in vital positions . . . [While] the district attorney’s office, sheriff’s office, and Los Angeles Police Department work in complete harmony and never interfere with . . . important figures in the underworld.”

Like a dissatisfied customer posting a Yelp rating, mobster Tony Cornero, whose happenin’ offshore gambling ships were the recent subject of a Times article, was said to have complained that he wasn’t getting the police protection he had paid for.

Prohibition in California had leveraged small-time operators into the big leagues. Because the Volstead Act — the operating manual for Prohibition — arguably loopholed 200 gallons of “non-intoxicating ciders and fruit juices” for an individual’s personal use, wink-wink, men like Dragna earned the gratitude of Inland Empire wine-grape growers by buying up and brokering grapes for the newly furtive wine trade. The mob added hard liquor to its menu, which amped up the hardcore crime and intra-gang battles it took to protect the bootleg racket, into the mix with prostitution, gambling and the like.

If things didn’t get too bloody too publicly, the city and the mob could keep a lid on things. “As long as it was quiet, no bloodshed in the streets,” Niotta figures, “then it was fine, because [L.A.] wanted to have this image of a family-friendly, fun, touristy place. But they also wanted these vices discreetly.”

But if crime got overloud, and moral crusaders demanded a banners-flying campaign against vice, the blue uniforms in the “white spot” city obligingly went in for crime theater and made enough penny-ante busts — couples drinking hooch in parked cars, random hapless hookers, sidewalk craps players, Italian families pouring Chianti at Sunday suppers — to quiet the indignant.

The big fish kept getting bigger.

After World War II especially, racketeers moved in on the popularity of restaurants and nightclubs. They leaned on the owners, or owned clubs themselves. Dragna’s Club Alabam, says his great-grandson, earned him a snazzy reputation as a “cafe man.”

Nightclubs attracted movie stars, and the movies attracted the mob the way they attracted everyone else. Even in his abbreviated stay here, Capone managed to take a tour of stars’ homes. A good-looking fellow named Johnny Rosselli was organized crime’s point man for its studio shakedowns. (One of Rosselli’s criminal stage names was Jimmy Hendricks.)

He pulled the strings of some studio unions to extort moguls with the threat of strikes — eventually he was convicted of extortion — but he was enough of a creature of Hollywood himself that he married an actress and produced a couple of crime films. He never got closer than his shoe-leather to a Hollywood Walk of Fame star, but you have to hand it to the man: He does have an IMDb listing.

Niotta thinks that it was L.A.’s almost idiotically complex civic sprawl — so many cities, so many city council members, so many cops and sheriffs — that paradoxically helped to keep organized crime from getting any more organized. It was just too expensive to recruit and pay off enough people in every city and police enforcement agency, “so if you were paying off the cops in [one] area, there’s always another pair of hands.”

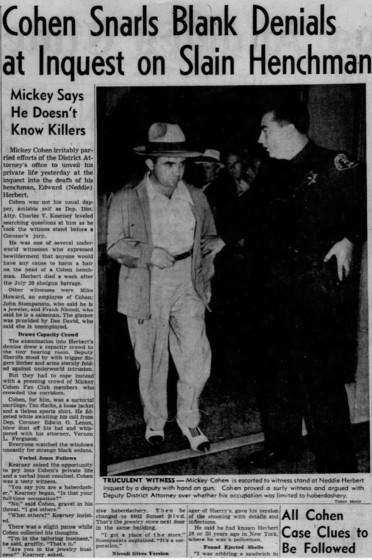

Courageous clean-government crusaders began to sanitize L.A. city government, but organized crime didn’t flag. A new generation of Italian and Jewish mobsters found L.A. to be fun and profitable. This was the legendary age of the West Coast mob: Dragna and the glamorous Bugsy Siegel elbowing into the racing news wire racket before Siegel was rubbed out — perhaps for not delivering on his big Las Vegas plans; Dragna trying to rub out Mickey Cohen for defying him.

And all the while, legalized vices in Nevada were beginning to leach the dirty lucre out of L.A. After Siegel’s murder, The Times editorialized sternly that Los Angeles was “No Winter Resort for Racketeers.”

Dragna was more than 25 years in his grave when Daryl F. Gates, the chief of the LAPD, summoned a news conference in the fall of 1984 and triumphantly announced a score of bookmaking conspiracy arrests, including the local mob capo, in Operation Lightweight.

“We feel the name is appropriate because organized crime is such a lightweight in Southern California," said the chief, with the note of acid mockery that reporters knew well. As for mob families, he taunted them as the “Mickey Mouse Mafia.”

By 1996, the California attorney general’s report on “Organized Crime in California” dwelled on the dangers of Russian mobsters and Asian street gangs, and was practically dismissive of “traditional” organized crime as “ineffective for many years because it has not been able to enforce its territorial control” here.

And it’s true, too, that, as Domanick pointed out, the corrupt decades of civic and mob crime in L.A. did ultimately beget the city’s clean-government protections like the civil service, and the commission and weak-mayor systems it has today.

Through all of his rummaging into his family’s history, Niotta found some personal solace in an FBI file he came across quoting an informant who said, in Niotta’s words, that Dragna had been “disgusted by the fact that the Mexican border was being used by the syndicate for narcotics. And he went back to New York and spoke to the [mafia families] commission about it. He was definitely against narcotics.”

Niotta was born long after Dragna died, but what, if he were given the chance, would be the one question he’d like to put to L.A.’s perhaps-classic godfather?

It took him a moment. “I’ve got about a million questions. If I could only ask one, I would ask one word: Why?”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.