As at Oxbridge, old-guard members' clubs are still serving comically bad food to the leaders of our country

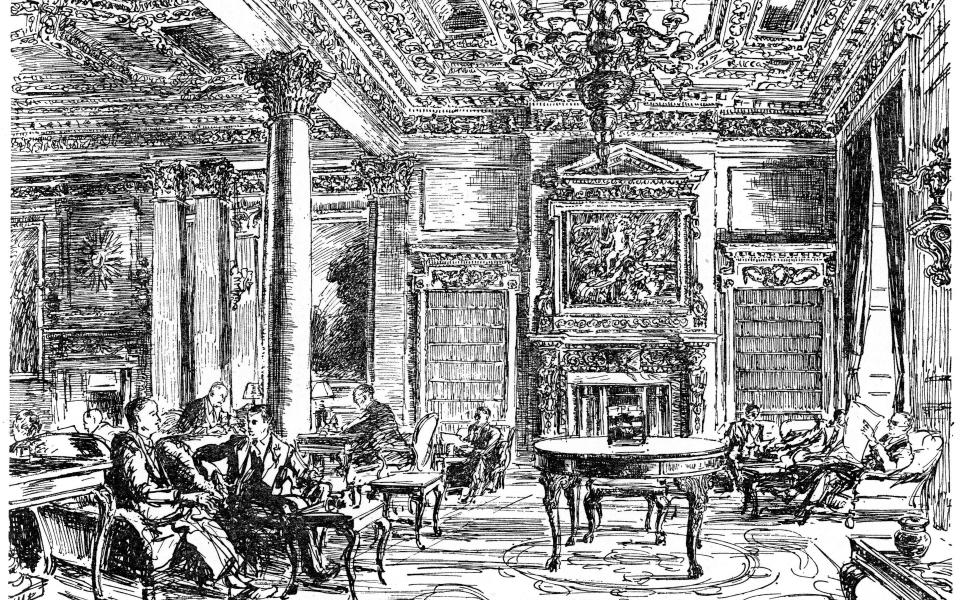

Every once in a while an invitation to join the Oxford and Cambridge Club drops out of my college magazine. And jolly civilised it looks, too, with its cream and gold plaster work as delectable as a fondant fancy, studded leather armchairs huddled around roaring fires and more chessboards strewn around than a set on The Queen’s Gambit.

The one thing that prevents me from downloading the application form is the memory of just how bad the food at Oxford was. My college, Exeter, was famous throughout the university for the comic awfulness of its catering. Part of me wonders if the woeful cooking was a ploy by the college authorities to get to the top of the Norrington Table. As any Buddhist monk will tell you, there’s nothing like fasting to sharpen the brain power.

A college friend who recently ate at the O&C describes the cooking as “not awful”, which is high praise indeed compared to some of the most prestigious names in St James’s clubland. Now a successful writer, he remembers a recent dinner on a hot summer night at The Reform Club. “The food was the kind of thing one might have had for a warming winter dinner in Victorian London - a savoury pastry tart, potatoes and two veg, and a heavy sponge pudding. There was a notable lack of fresh fruit or anything like a salad.”

While the St James’ restaurant scene innovates with the lauded likes of West African-influenced Ikoyi the eclectic fusion of Scully, or the new, glamorous Italian Bardo St James, the kitchens of its members’ clubs remain as pickled in aspic as the jellied meats one might expect to see on the menu.

“I’ve eaten at The Reform Club several times,” my writer friend says, “and it has more in common with institutional catering than restaurant food - closer to the school dormitory or the Oxbridge college than to the tables of nearby Soho. My hunch is that most of the men who dine there can’t cook for themselves, and so the food could be of any standard because the alternative is starvation.”

There is a very funny scene in Alan Hollinghurst’s debut novel, The Swimming-Pool Library, when his hero William Beckwith, himself just down from Oxford, has lunch with the elderly Lord Nantwich at the fictional Wicks club. "The air retained a smell of bad cabbage and bad cooking that made me apprehensive about lunch," Beckwith says, before tucking in to a "quite flavourless’ trout and ‘family-hotel trifle". The novel is set in 1983 but the meal served could just as easily be eaten on Pall Mall in 2021.

Wicks, of course, sounds not unlike White’s, the oldest and most exclusive of London gentlemen’s clubs which counts Prince Charles and Prince William among its members (the Prince of Wales held his stag do there before marrying Lady Diana Spencer). White’s began life as a hot chocolate seller in 1693 and has adhered to a culinary philosophy of simple things done well ever since: Welsh rarebit, Scotch woodcock, potted shrimps.

Boodles, founded almost a century later in 1762, is perhaps the only club with a reputation for food that could pass muster in a West End restaurant. Harry Wallop, author of Consumed: How We Buy Class in Modern Britain, has been a regular visitor to Boodles as a guest of his father, though it is visits with his mother that he looks forward to the most.

“On the ladies’ side it really is quite decent,” he says. “You might get lobster ravioli or French classics like an Armagnac soufflé. For some reason it has been decided that’s too fancy for the men, who just get a roast.”

Wallop, who attended Radley College before Oxford, says that the idea of institutional comfort food holds no appeal to anyone under 50 – “it's not comforting, it’s nightmare inducing” – and that the very notion of the gentlemen’s club faces extinction as members die off.

“If these clubs just allowed one of their floors to be a sort of very grand WeWork for posh people, that would make a lot of sense. But most of them have a no working policy. I’d be surprised if they were still around in their current form in another 20 years.”

The new Pavilion Club in Knightsbridge, a mix of workspace and members’ club, might be a template for the future. Tom Kerridge, of Marlow’s two Michelin-starred Hand and Flowers, oversees the cooking, which has been kept as informal as possible. “It doesn’t operate like a restaurant,” Kerridge says. “There are menus, but the food is designed for people who are hot desking. There’s steak tartare, salads and loaded fries, and we’re putting in a wood-fired pizza oven, because that’s what members want. We’re not precious about what we cook because the reason that the members are there is about much more than the food.”

There are, of course, many famous London restaurants that are successful for reasons that have nothing to do with the food: the celebrity-spotting at Joe Allen, say, or the nothing-is-too-much-trouble service at The Ivy. No one goes to a St James’s club expecting a gourmet experience. A Harley Street consultant I know was appalled to see a steward deftly trap a mouse under a cloche in the dining room of the Royal Automobile Club. A supper punctuated by plaintive squeaks echoing from beneath a silver dome is, he says, the price one pays for the best pool and squash courts in central London.

But while the food at most clubs isn’t likely to win a Michelin star any time soon, the wine cellars are often a thing of wonder. 67 Pall Mall, a comparatively recent arrival on the SW1 club scene, was founded on the notion of good drinking. City trader Grant Ashton opened the club in 2015 after realising he had bought and stored more wine than he would ever be able to drink – as had many of his friends.

“I formed a club where members could drink the bottle they really wanted without feeling fleeced by excruciatingly high mark-ups,” Ashton says, “as well as summon a bottle from their own stash in the cellar. Our membership is a diverse mix of financiers as well as wine trade professionals.”

But has the day come when a members’ club opens a restaurant it is so proud of that it wants to share it with non-members? The Conduit, the eco-minded Covent Garden club with a mission to drive social change, launches an open-to-all restaurant called Warehouse next month, with an emphasis on zero waste and sustainability.

“We decided to build Warehouse for the public because we want a broad community to be able to access both the remarkable food and the ethos behind it,” Conduit founder Paul van Zyl says. “Every dish has a story and every ingredient has been delivered with flair and with attention to its impact on the world.”

None of that, of course, is likely to trouble the denizens of St James’, snoozing off lunch in a leather-lined library. “The gentlemen’s club is the last refuge from the wokerati and everything that is awful and horrible about the modern world,” Wallop says, tongue firmly in cheek. “Your martini is properly dry, your food lines your stomach and the only foreign thing is the wine.”

Each to their own, of course. But I shan’t be trading in my Soho House membership any time soon.