Why parts of Philadelphia will close to cap I-95 and why Wilmington can’t make it work

Make sure to add some extra travel time if you're planning to visit Philadelphia this weekend — parts of I-95 will be completely closed from Feb. 3-6 for demolitions between Chestnut and Walnut streets in Center City, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation.

Anyone driving north on I-95 from 6 p.m. on Feb. 3 to 5 a.m. on Feb. 5 will be detoured between the exits at Columbus Boulevard (Exit 20) and I-676 (Exit 22), PennDOT said. One lane will be closed between these exits earlier in the day on Feb. 3.

Capping I-95

The closure is one of many planned in the area for this year as part of the $329 million I-95 Central Access Philadelphia, or CAP, project to revitalize the area near the Delaware River waterfront. Much of the project revolves around the creation of a park at Penn's Landing, which the Delaware River Waterfront Corp. describes as a "civic space" for food and drinks, kid play areas, performances, festivals, ice skating and improved pedestrian access to the river.

The project represents the latest iteration of a national trend of highway capping, the creation of public spaces overtop highways connecting the neighborhoods on either side of the road. Many caps include green spaces and bike paths intended to provide access to nature in urban areas.

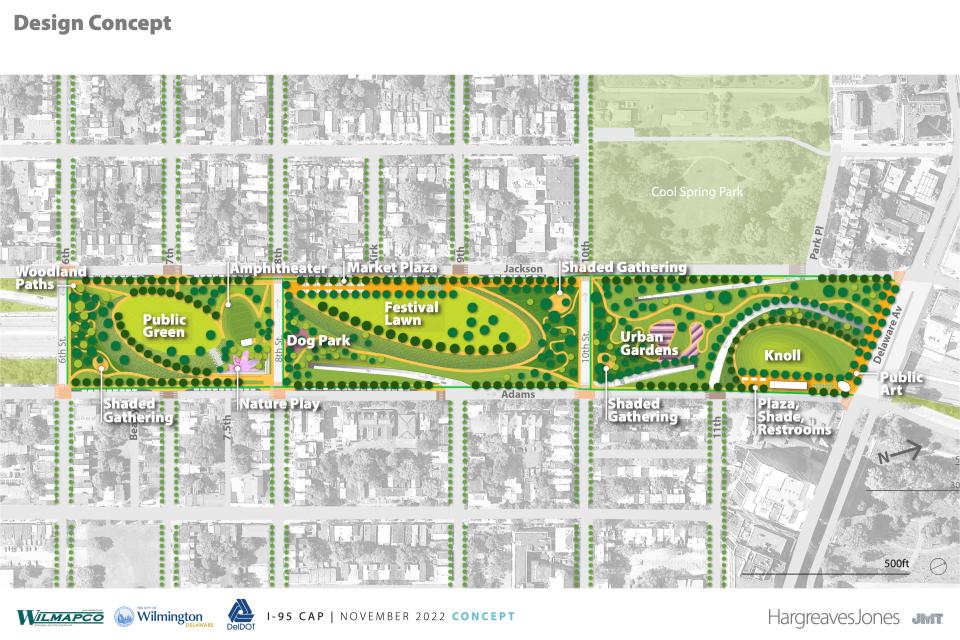

Wilmington has tried — and repeatedly failed — to implement its own cap over I-95 near West Center City. The proposed cap would span the six blocks between West Sixth Street and Delaware Avenue. It would also cost hundreds of millions of dollars and take at least a decade, according to a feasibility study published in early 2023.

The study had four main goals: reconnecting the neighborhoods divided by I-95; support neighborhood "character, cohesion and pride; "improve safety for pedestrians and bikers; and create "vibrant public urban outdoor experiences" for people living nearby.

But even if the city is able to secure the funds, experts say the construction poses another problem: green gentrification.

What is green gentrification?

Green gentrification, also called environmental gentrification or ecological gentrification, is when providing green amenities like parks or highway caps to a poorer, often marginalized neighborhood drives up property prices, encouraging wealthier people to move in and driving out the existing residents.

University of Delaware professor Victor Perez said there's no surefire way to know whether a project like the proposed cap in Wilmington or the current CAP project in Philadelphia will lead to green gentrification. Gentrification is a "long-term process," Perez said, so it's impossible to know immediately what impact may be had on the surrounding community.

These "greening" projects are often paradoxes: While there are benefits to adding green spaces, such as improved mental and physical health and better social cohesion, "it's a real challenge to benefit equitably from those types of interventions."

Gentrification in Wilmington

Perez said that community members don't always make the connection between greening in the area and gentrification. He referenced the development of the South Wilmington Wetlands Park in Southbridge, a majority-Black and low-income neighborhood, which was initially proposed by residents in 2006 to help mitigate flooding.

And while the park itself may bring health and safety benefits to the community, Perez said those benefits may be short-term. Development and gentrification are already underway on Riverfront East, which the landscape architect described as "the next iteration of development, following the successful revitalization of the northeast bank (of the Christina River) in decades prior."

"There are many threads of economic and environmental renewal in Wilmington that, on paper at least, are all signals of coming displacement and gentrification for a handful of communities," Perez said.

Some defend against questions of potential gentrification in the city by pointing to the Riverfront, as development did not displace people from the nearby Browntown neighborhood.

But Perez said it wasn't a concentrated effort that prevented the gentrification: It was the highway.

The building of I-95 through Wilmington has served as a division between neighborhoods since the 1960s. It has also staved off development from the Riverfront spreading further west.

Building the cap, proponents say, would help reconnect a divided West Center City and create more unity in the community.

But if the city doesn't take the necessary steps to prevent gentrification, Perez said, the highway cap wouldn't bridge the people living in the area now for long. Proactive measures like rent control and deep community involvement through all steps of the process are crucial to ensuring that current residents aren't displaced, according to Perez.

As of January 2024, the proposed I-95 cap in Wilmington still has not been funded.

Send story tips or ideas to Hannah Edelman at hedelman@delawareonline.com. For more reporting, follow them on X at @h_edelman.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: I-95 capping project continues in Philly. How it could affect Delaware