Why the Pentagon Is Suddenly Declassifying Lots of Info About What's in Orbit

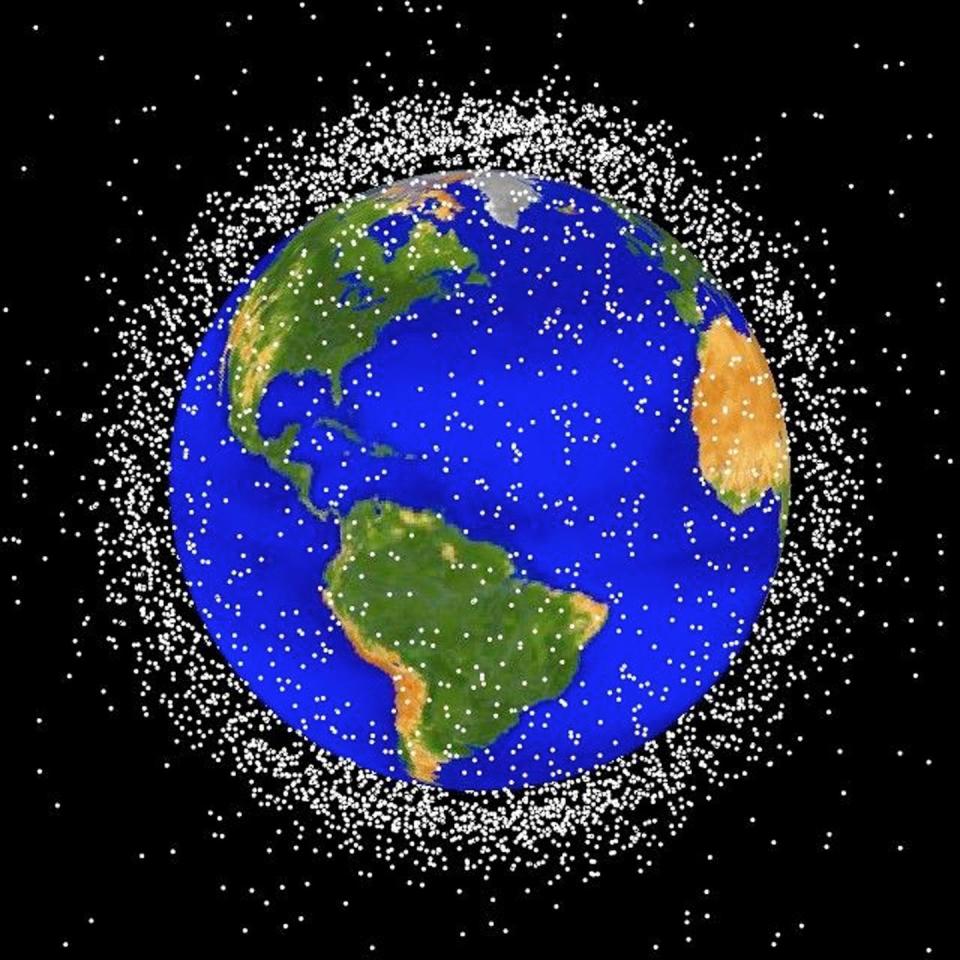

Not many people need direct access to what the U.S. military calls “space situational awareness,” a fancy term for knowing what manmade objects are in space, and where. But those with an eye on Earth’s orbit now have access to a trove of never-before-seen data about space objects that before now the government has kept secret.

The declassification effort, announced in October, yielded another release of data last week. “This is us being transparent, leaning forward and trying to enhance that spaceflight safety through data sharing,” Col. Scott Brodeur, the commander of the Combined Space Operation Center, tells Popular Mechanics.

Contested and Congested

These orders come from the top, and are part of the larger U.S. government effort to spur the commercialization of space. The largest sign of this change in policy is the transfer of space traffic management from the Pentagon to the Department of Commerce. U.S. Strategic Command officials say the move to declassify is “based on guidance in Space Policy Directive-3” which stipulates that Commerce will be responsible for making space safety data available to the public, while the Department of Defense will still be in charge of keeping an authoritative catalog of manmade space objects.

That catalog is accessible to the public via a website, space-track.org. The site provides what are called two-line element sets, or TLEs, that encode the position and probable movement of an object in orbit. McKissock, the lead for space situational awareness sharing at the 18th Space Control Squadron, says the government recently released TLEs for more than 500 previously classified objects, and is working to put out more data. "So we are exploring every avenue to share more information in the right way,” McKissock says.

She says that as more and more civilian companies from across the world cast objects into orbit, the American space traffic management effort will need to be more expansive. “We're looking forward to working with our civil counterparts on how we can better support the global community as space becomes more contested and congested,” McKissock says.

The global community of amateur satellite trackers, who relish in following the movements of clandestine spacecraft, seem appreciative but not exactly blown away by the disclosures so far. “If one is making the claim to improve space situational awareness safety as the reason, then disclose all of it,” says Scott Tilley, of the sat-tracking blog Riddles in the Sky. “At least we are moving in a direction of less classification of space objects.”

Orbital Traffic Cops

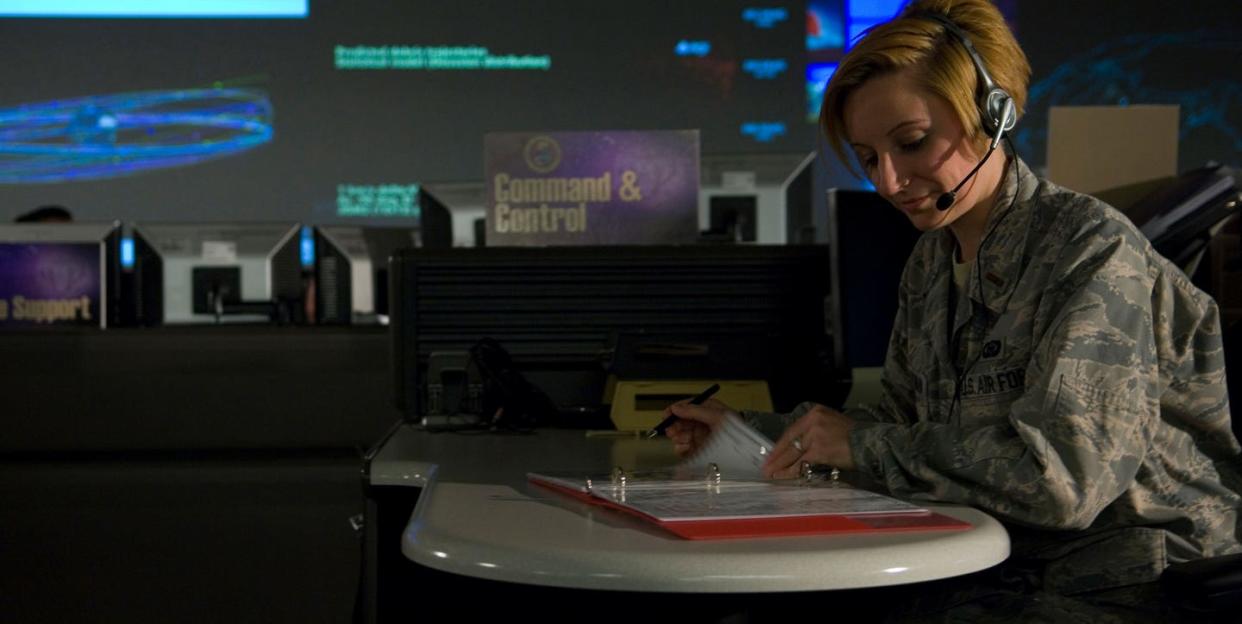

All day, every day, the Combined Space Operations Center (CSPOC) performs a data symphony that reveals what's going on in Earth orbit. Col. Brodeur is the conductor. He oversees heart of the system: the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, ground and space-based sensors that collect data on manmade objects in space. Brodeur orders about 300,000 operations per day to this sensor network, creating data that the 18th Space Control Squadron processes. The resulting catalog (minus sensitive data about U.S. objects) is what is available on www.spacetrack.org.

Brodeur's office needs all these numbers to do the many jobs in its mandate, including keeping an eye on space weather, tracking launches across the world, and providing infrared intelligence imagery to battlefield commanders. One job of growing importance is warning satellite owners about possible orbital collisions, which the pros call a “conjunction event.”

“We don't only provide data to the CSPOC and to our own Department of Defense partners. It's really to the entire world,” McKissock says. “And we don't just provide conjunction assessment to the people who like to talk to us. We provide it to every operator of an active spacecraft unequivocally. We send those notifications to China. We send them to Russia."

While working with international partners (and potential adversaries) is important, the biggest changes happening in space are coming from the commercial sector. The U.S. government is itching to see an orbital economic boom. To that end, one new point for civilian-military collaboration is the "commercial integration cell," a permanently staffed desk on the operations floor of the CSPOC.

“There are two individuals who interface between the eight companies that they represent in our day-to-day operations,” says Brodeur. “The most correct term for those folks would be consultants. But they are paid by the commercial companies all together. They cover their salaries."

The eight companies are Intelsat General, Inmarsat, Iridium, UltiSat, SES Government Solutions, Digital Globe, Extar and Viasat. These companies have a direct pipeline into the U.S. government’s space traffic experts, so their sat operators get immediate warning over dangers in orbit from a collision, space weather or a hostile act.

Brodeur says the companies' cooperation can help the U.S. government as well. During an emergency, for example, JSPOC is eager for any data it can get. For example, Brodeur said Digital Globe provided imagery to help search and rescue and recovery efforts during the recent east coast hurricane. “They benefit from having a relationship with us,” he says. “But there are many, many examples, of how we benefit from having that relationship with them.”

Still, one thing missing from the equation is the small satellite operators. One of the biggest looming trends for space traffic are the networks of mega-constellations of small sats in low-Earth orbit. Firms like SpaceX and Blue Origin have plans to launch thousands of sats, and dozens of startup companies promise affordable Cubesat and microsat launches.

McKissock says that the challenge is real, but the solution is the same. “A really important part of the 18th Space Control Squadron mission is early engagement,” she says. “The more we understand about their mission, and their CONOPS, the more we can be prepared to support what they're doing and maintain tracking on all of them.”

That certainly includes small sats. “As far as what people like to call 'mega constellations' that are coming into low earth orbit, we have been in contact with them,” she says. “Right now, we're working with all of those new entrants in to space to basically help them do the best risk analysis they can do. So, when they do launch these larger constellations, they're doing it as responsibly as possible.”

What Is Secret, What Is Not

It’s not easy to get a review of the quality of the data being released, but the amateur but dedicated satellite tracker community is a good place to start. Scott Tilley, who co-writes the Riddles in the Sky blog, noticed the most recent release of new data on Spacetrack and has taken a close look at what’s there.

“Largely speaking, they have released data on objects that the public could find the locations of using other means,” he says. “The share is very welcome. But it is limited, cloaked in secrecy itself and only reveals the obvious for objects with plenty of public references about their locations.”

Still, he says the data released so far will prove useful. “This doesn't really change satellite tracking other than it reduces the number of objects we will need to track,” he says. “We can use this information as a historical check on our data and look for anything interesting particularly in the transfer orbit stage.”

Sat trackers monitor the TLEs of unclassified missions to learn the behavior of the spacecraft. Any other launch that uses the same satellite bus will likely behave the same on its way to orbit. “This allows us to learn enough to identify specific hardware versions of classified launches later that use the same hardware,” Tilley says.

He also reserves some skepticism when it comes to the data itself. For example, amateur trackers are following the movements of an Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) satellite as it moves toward geostationary orbit. These satellites serve as emergency communication during a nuclear war. They can also defeat intentional jamming from enemies, surging their signal strength to overwhelm any noise, while nulling antennas pinpoint the attack and dampen the signal with counter-noise.

In other words, it’s the kind of satellite position that the Pentagon may not want to advertise accurately on a public website. “We are presently monitoring the transfer of AEHF-4 into GEO orbit,” notes Tilley. “And the data posted by Spacetrack seems to vary from our observations.”

No matter what the future holds, there will be a cat-and-mouse between these amateur sat trackers, and their government equivalents in Russia and China. Brodeur says there will be a limit to what can be released. “I don't see the secrecy going up,” he says. “But I don't know that we'll have a 100 percent transparency.”

('You Might Also Like',)