Why police nationwide rarely face charges when they kill in the line of duty

Public judgment came quickly for the Akron officers who killed Jayland Walker last summer after a car and foot chase.

The eight officers acted in a way that's “consistent with use of force protocols and officers’ training,” the Akron police union said July 3, just minutes after the city released body-worn camera footage that showed Walker's body twitching on the ground as dozen of rounds hit him.

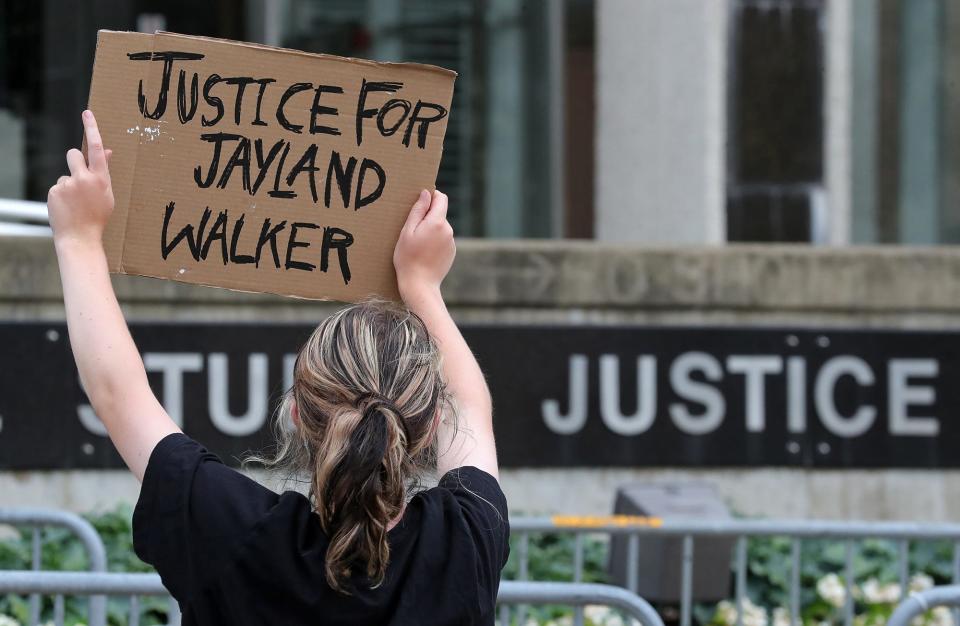

Protesters in the streets of Akron labeled the police shooting a murder.

“We don’t treat animals that way," an attorney for the Walker family said.

In recent weeks, the killing has become a key issue in the race for Akron mayor, with two candidates — Joshua Schaffer and Keith Mills — also calling Walker's death by police "murder."

With bated breath and fresh plywood over windows, the community is now bracing for a special grand jury to decide this month whether the use of deadly force merits criminal charges.

Jurors will be instructed to answer a core question: Would a reasonable officer, in that moment and not in hindsight, have taken the same action?

But the circumstances of Walker’s death and the possibility that the use of force will be deemed justified fit an American pattern in law enforcement that some experts find troubling.

Summit County special grand jury: Ahead of Jayland Walker case, what we know about the grand jury process

No officer convicted in Summit County

As far back as the Summit County Prosecutor’s Office can tell, which is 2001 when Sherri Bevan Walsh took office, only one use-of-force incident led to charges against officers.

Summit County Sheriff's Deputy Stephen Krendick was charged with murder in the 2006 death of Mark D. McCullaugh Jr., 28. After a violent struggle with five deputies in his cell at the county jail’s former mental health unit, McCullaugh died by asphyxiation from blunt-force blows and the combined effects of chemical, electrical and physical restraints on his airway, an autopsy concluded.

Jayland Walker case: What the state investigation of fatal Akron police shooting may reveal

At the end of an eight-day trial in 2008, a judge appointed by the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that McCullaugh’s death was “more likely” due to “sudden cardiac death” resulting from the exertion of the struggle and a preexisting cardiovascular condition.

Following Krendick’s acquittal, the state dropped charges against the other four deputies.

An insurance company covering Summit County government paid McCullaugh’s family $862,500. The city of Akron and other jurisdiction have also settled lawsuits stemming from their officers’ use of force, but no other officers have been criminally charged for using force in the county.

'Business as usual'

Since 2000, 35 people have died during encounters in which officers in Summit County fired their weapons or used force, including tasers. With grand jury decisions pending in the Walker case and another on the February 2022 shooting death of Lawrence LeJames Rodgers by Akron police, every case was deemed justified by the Summit County Prosecutor’s Office or cleared by grand juries.

Akron police officers were involved in 22 of the cases, including a joint response with university police in 2002 when an armed man barricaded himself in a bathroom for 10 hours and was shot after being forced out with tear gas.

Akron police are averaging one fatal shooting per year while responding to 150,000 or more calls for service.

“Officers do not face any criminal charges for the people they kill while on duty,” said Matthew Stinson, a professor in the criminal justice program at Bowling Green State University. “And that's really considered business as usual, because in most of these cases, the officers are found to be legally justified.”

Stinson maintains a national database of criminal charges against officers who shoot and kill. At least 98% of the time, there are none, he said.

Based on tracking by The Washington Post, more than 1,000 people are shot and killed by police every year.

Fewer than 10 police officers criminally charged per year nationwide

Fewer than 10 officers on average are criminally charged each year in America, according to Stinson’s research, which excludes federal law enforcement and goes back to 2005.

“People read about these in the local newspaper. They hear about them on the evening news,” Stinson said. “But it's not until you aggregate it that it's troubling.”

Less than half of all charges against officers result in conviction.

Of the 165 officers charged since 2005, 52 have been convicted — none in Ohio, where eight officers have been charged. And 55 cases are pending, including three in Ohio. The 52 convictions nationwide include seven murder charges, 29 manslaughter charges, six homicide charges, five civil rights violations, two official misconduct charges, two assault charges and one charge for reckless discharge of a firearm.

Sentences for manslaughter or homicide convictions averaged five years with a range of no prison time to 40 years. The seven officers convicted of murder are serving 81 months to life in prison.

What Stinson finds particularly concerning about the Walker case is the number of officers involved.

Forty seconds after Car 24 attempted to stop Walker for an alleged traffic and equipment violation on Tallmadge Avenue, the officer reported a gunshot from inside Walker’s car. Other officers heard that call on the radio and responded.

“I would argue that there was a lack of situational discipline,” Stinson said of at least 11 cruisers pursuing Walker and 13 officers chasing Walker on foot. “The supervisors did not have a discipline response there. In other words, they didn't have control of it.

“So in my view, that's the crux of what needs to really be investigated here,” Stinson said, “to understand what the hell was going on.”

The head of the Akron police union, Clay Cozart, has said the officers pursuing Walker saw him earlier that night but did not give chase. And they knew he’d evaded a traffic stop in New Franklin the night before.

Perceived threat key to justifying use of deadly force under U.S. law

What happened when officers blocked Wilbeth Road, forcing Walker to abandon his rolling vehicle on foot while wearing a ski mask, is critical to determining the threat officers perceived.

And a perceived threat is central to the justification of deadly force under American law.

The graphic images captured by body-worn cameras tell “what's happening,” said Wellington Chief of Police Tim Barfield, who trains officers in Ohio and elsewhere on proper use of force. “But it doesn't tell you what's going on. And video doesn't have fear. It’s not going to get shot. So, the problem with just looking at the video is you don't know what the officers were thinking. You weren't there.”

Eight officers fired, according to Akron police. Muzzle flashes or smoke from their barrels is visible in seven of the 13 camera angles released a week after the shooting. Some officers fired only a couple shots then stopped. Others dropped their empty clips on the ground after the firing ended.

In seven seconds of firing, some officers first shot while Walker is upright and others in the next second as he fell or had already hit the ground.

Human performance factors

BCI investigators will consider what Barfield called “the totality of circumstances” leading up to the officers discharging dozens of rounds at Walker.

En route to the scene, the officer in Car 24 got on the radio. “Take caution," he said. "He was grabbing for a gun, and he did fire a shot out the side of the door.”

In a press conference on the day the video footage was released, Akron Police Chief Steve Mylett said each of the officers was sequestered and monitored at the scene. It's unclear if BCI investigators, local police supervisors, the department’s internal affairs unit or all of the above questioned the officers.

“When the investigative team arrives, they do an individual walkthrough of the crime scene,” Mylett said. “Each officer, independent of each other, related that they felt that Mr. Walker had turned and was motioning and moving into a firing position.”

Wellington, a village in Lorain County, had its first officer-involved shooting in 63 years on July 23. An officer tased and then shot a man with a history of mental illness. The man, who refused to drop a knife during the incident, was hospitalized in stable condition after the incident.

Barfield spoke to the Beacon Journal on July 14. He said research shows that officer accounts taken immediately after a traumatic incident can be unreliable. The human mind has its limits. With adrenaline pumping and the anticipation of violence, officers focus on the threat and miss other details. Their recall is impacted by what Barfield and experts call human performance issues.

“The human body can only process so much, can only do so many things,” Barfield said. “Under stress, we get tunnel vision.

“If the public and the media and the politicians and maybe a few police chiefs actually understood human performance a little bit better, than we wouldn't be so quick to judge the situation,” Barfield said. “Should we always learn and improve? Absolutely.”

Officer recall not always reliable

In the book "Deadly Force Encounters" by Alexis Artwohl, the retired clinical and police psychologist gives examples of officers forgetting they ever called loved ones immediately after traumatic experiences on the job.

A Beacon Journal review of civil lawsuits involving deadly use of force in Akron found that officer recall, when questioned at the scene or shortly after, can change drastically over time, from not being able to remember if the suspect was holding a gun or who fired first or if they even fired their own weapon (even in cases when they did) to remembering weeks or months later, with certainty, that the suspect not only reached for a weapon but was pointing it at them.

Experiments have put officers in shoot-or-don’t-shoot situations. Afterward, some officers have trouble recalling an air horn blast during the experiment.

Barfield said research increasingly suggests officers can more accurately recall details of traumatic events after two or three sleep cycles. BCI staff investigating deadly use of force typically waits two or three weeks to interview officers, based on other completed investigations.

Another phenomenon of police shootings involving multiple officers is “contagious shooting,” or when officers hear a gunshot without knowing who fired and react with the impulse to return fire.

“Maybe it's contagious shooting,” said Barfield, who has four decades of law enforcement experience. “Maybe they all perceived the threat at the same time.”

Supreme Court decision sets standards for justified use of deadly force

Criminality in the use of deadly force, as well as officer training on when it's appropriate and justified, is measured against the seminal 1989 U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Graham-versus-Connor case.

Before the watershed case, victims and prosecutors had to prove malicious intent on the part of the officer. After the case, jurors and judges had to come to the conclusion that any other reasonable officer in the same circumstances in that same moment, not in hindsight, would have acted the same.

The details of the Graham case offer a contextual backdrop for public understanding of why officers often avoid charges after killing unarmed people, even people committing no crime.

In 1984, Dethorne Graham panicked during an insulin reaction. A friend drove the diabetic to a nearby convenience store in Charlotte, North Carolina, for orange juice. But the line was too long, so Graham ran from the store to go to another friend's house for help.

A police officer, suspecting Graham might be intoxicated, detained him and his friend after a traffic stop. The men were released after the officer determined no crime was committed, but Graham sued, alleging that his constitutional rights prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment or unreasonable searches and seizures had been violated.

Lower courts agreed. But the Supreme Court overturned those decisions and sent the case back to be decided on an "objective reasonableness" standard.

In its unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court said jurors in use-of-force cases should consider factors laid out in an older case called Tennessee v. Garner, which required the examination of the severity of the crime, threats perceptively posed to the public and other officers, and whether the individual was fleeing or resisting arrest.

Reach Doug Livingston at dlivingston@thebeaconjournal.com or 330-996-3792.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Police who kill on duty criminally charged less than 2% of the time