Why Do Queer People Love Classic Movies?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Classic Films' Appeal to LGBTQ+ Fans

Women in slinky gowns or suits with big padded shoulders. Men (and sometimes women) in tuxedos or trench coats and fedoras. Hanging out in ritzy nightclubs or smoky dive bars. And somewhere in there, a character who, though it’s not stated, just has to read as gay.

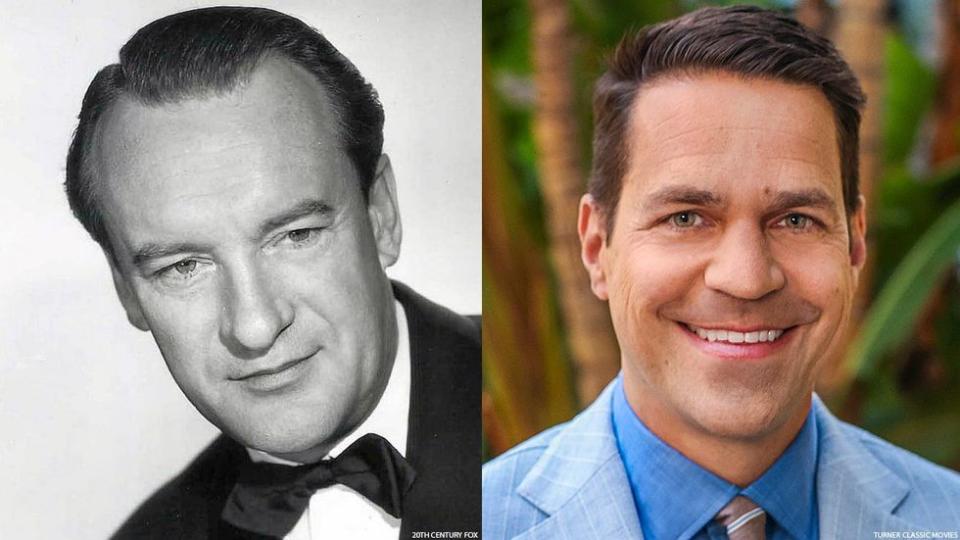

Hollywood glitz and coded portrayals — those are some of the main reasons many LGBTQ+ cinephiles love films from the classic era, the 1930s through the 1950s and a little bit beyond, says out Turner Classic Movies host Dave Karger.

“There’s something about the old Hollywood glamour that the LGBTQ+ community appreciates,” Karger says. The stars were larger than life — “there’s something to be said for that,” he notes.

“I can speak from experience,” he adds. “It was my gay male friends who helped introduce me to classic film.”

Also, while there were certainly some action movies in that era, the big screen wasn’t yet dominated by superheroes and special effects — films told stories of human drama, Karger points out.

Unfortunately, under the studios’ self-censoring Production Code, in full effect beginning in 1934, meant that human drama couldn’t include overtly queer characters. But under the code, there was a lot of coding — depictions of characters that in-the-know audiences could identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer.

“It’s fun to see how certain filmmakers managed to skirt those rules,” Karger says. “That’s all that we as a community were allowed for decades.”

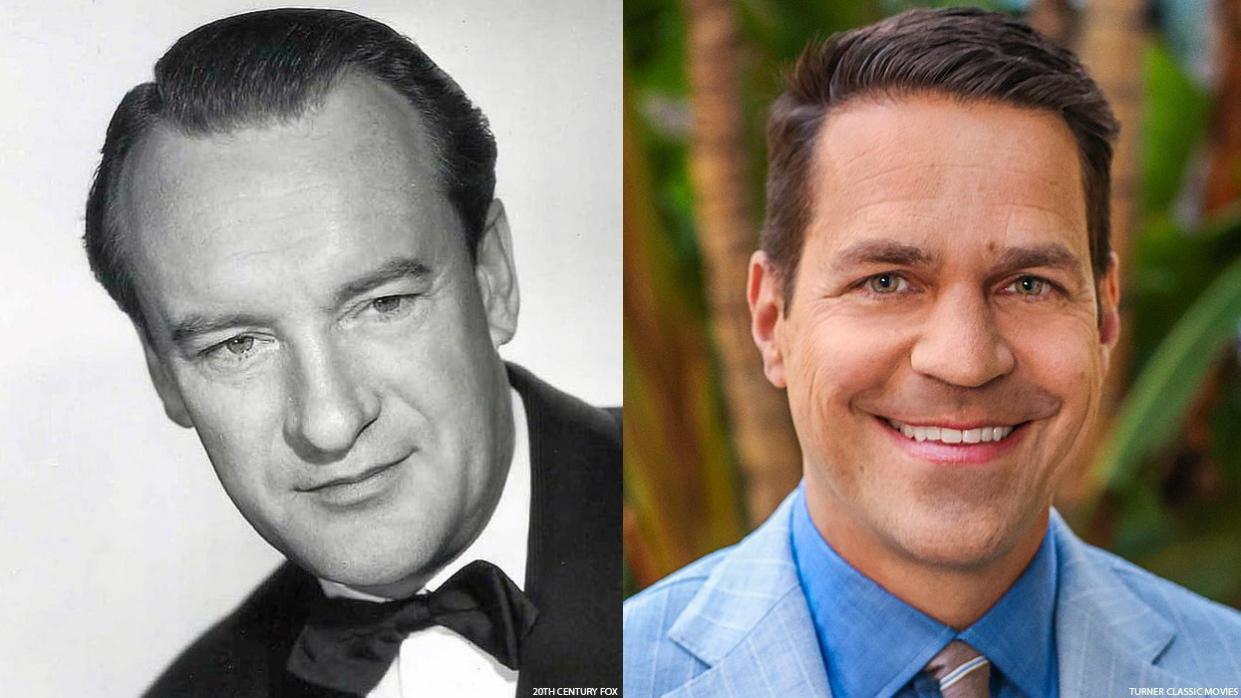

Some of those coded (or perhaps not-so-coded) portrayals: Greta Garbo kissing a woman as the titular Queen Christina of Sweden. Farley Granger and John Dall as two men who are pretty clearly lovers in Rope. Judith Anderson as Mrs. Danvers, the housekeeper obsessed with the late Rebecca de Winter in Rebecca. George Sanders (pictured, left) in his Oscar-winning turn as acid-tongued theater critic Addison DeWitt in All About Eve; Karger describes DeWitt as “possibly my favorite character in my favorite film.”

Many of these and other coded queer characters aren’t likable, and there’s no happily ever after for queer couples in classic-era films. But they’re often strong characters and memorable ones.

As the Production Code’s enforcement weakened in the 1960s (in 1968, it was replaced by the current rating system), portrayals of queer characters grew clearer but not necessarily better. These characters usually met with disgrace or death. “It’s not like great progress was made immediately,” Karger says.

Vito Russo wrote what is still the definitive analysis of queer characters in classic film, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, first published in 1981 and revised in 1987. The 1995 documentary based on the book will kick off TCM’s Pride programming that starts Monday night and continues into Tuesday morning.

Karger and writer-comedian Louis Virtel will introduce the slate of six films. “He’s so smart and so funny,” Karger says of Virtel, who happens to be a former Advocate intern. “I cannot wait to hear what he has to say.”

Scroll on for info about the featured films.

The Celluloid Closet (1995)

Vito Russo’s book is translated to the screen by the writing and directing team of Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. Lily Tomlin narrates; the talking heads include Gore Vidal, Quentin Crisp, Armistead Maupin, Shirley MacLaine, Tony Curtis, and many, many more; and there’s a wealth of clips from classic-era movies. “I think The Celluloid Closet is an absolute must-see for any classic movie fan,” LGBTQ+ or not, Karger says. 8 p.m. (all times Eastern).

Pictured: Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon pose as women in director Billy Wilder’s 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot. The film was recently reimagined as a Broadway musical with an expansive view of gender.

Rope (1948)

Bisexual actor Farley Granger (left) and John Dall (right) star as two murderous young lovers. No, not a positive portrayal, but a fascinating one. James Stewart plays against his nice-guy image as a cynical professor. The film, adapted by gay writer Arthur Laurents from a play by Patrick Hamilton, was most noted on its initial release for director Alfred Hitchcock’s experiment of shooting in long, continuous takes. It was judged a failure at the time, but its reputation has risen since. 10 p.m.

The Children's Hour (1961)

It still wasn’t a progressive time for queer characters. Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine run a private school for girls, and a dissatisfied student claims they’re lesbians. We won’t give away the ending except to say it isn’t pretty. Based on Lillian Hellman’s play and directed by William Wyler. Hellman’s play had been adapted for film in 1936 as These Three, which turned the rumor of a lesbian relationship into one of heterosexual adultery. It was also directed by Wyler. 11:30 p.m.

Queen Christina (1933)

Greta Garbo stars as the 17th-century Swedish queen. She falls in love with a Spanish diplomat (John Gilbert) but also plants a kiss on the lips of lady-in-waiting Ebba (Elizabeth Young). Friendship or passion? It’s open to interpretation. Garbo wears male clothing through most of the film as well. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian. 1:30 a.m.

Victim (1961)

One of the first sympathetic portrayals of homosexuality. Dirk Bogarde (gay in real life) is a prominent British lawyer, a closeted gay man married to a woman, and he risks his reputation when he finds out about a blackmail plot against a former lover (Peter McEnery, pictured right, with Donald Churchill). Directed by Basil Dearden, the film takes a stand against the criminalization of gay sex. 3:30 a.m.

Tea and Sympathy (1956)

Well, sympathy for those “accused” of being gay. A prep-school student (John Kerr) is taunted by his classmates for being too “sensitive.” The headmaster’s wife (Deborah Kerr) takes it upon herself to affirm the youth’s heterosexuality. Famous line: “Years from now, when you talk about this — and you will — be kind.” Adapted by Robert Anderson from his play and directed by Vincente Minnelli. 5:30 a.m.