Why it’s so rare for Congress to expel a member

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It almost seems to be harder to get kicked out of Congress than it is to get elected in the first place.

There’s been no shortage of scoundrels elected to the House and Senate, but only an exclusive few have actually been expelled – although the Constitution explicitly gives both chambers the power to “with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.”

Rep. George Santos – the New York Republican with problems telling the truth and who is under federal indictment for fraud, money laundering, theft and stealing donors’ identities – became just the third federally elected lawmaker since the Civil War, and the sixth ever, to be kicked out of the House by his peers with a bipartisan vote Friday.

Few get this far

It takes a special blend of bad behavior and tolerance for shame to get to the point of actual House expulsion.

The only other expelled representatives since the Civil War had already been found guilty in federal court and still refused to resign.

Michael “Ozzie” Myers, a Pennsylvania Democrat, was expelled from the House in 1980 after he was convicted as part of an infamous FBI investigation known as ABSCAM, in which he and other lawmakers were caught up in a sting operation taking bribes to help a fictional Arab sheikh.

Most of the other lawmakers embroiled in ABSCAM ultimately resigned. Myers was expelled in the time between his conviction and his sentencing in 1980.

He’s actually back in jail at the moment; Myers, now 80, was sentenced to 30 months in prison last year for taking bribes in a ballot-stuffing scheme in Democratic primaries dating back to 2014.

The other House member to be expelled since the Civil War, James Traficant Jr., an Ohio Democrat, was removed from office after being convicted in a bribery and racketeering scandal in 2002. Traficant tried to mount an independent campaign for his seat from his prison cell, but it did not go well. He died in 2014 after a tractor accident on a family farm.

Santos, unlike Myers and Traficant, has not been convicted

Although Santos is awaiting trial, the House Ethics Committee went ahead and issued an incredible and unanimous report accusing him of breaking laws and stealing from his campaign.

Here’s one particularly strong passage from the report:

Representative Santos sought to fraudulently exploit every aspect of his House candidacy for his own personal financial profit.

He blatantly stole from his campaign.

He deceived donors into providing what they thought were contributions to his campaign but were in fact payments for his personal benefit.

He reported fictitious loans to his political committees to induce donors and party committees to make further contributions to his campaign — and then diverted more campaign money to himself as purported “repayments” of those fictitious loans.

He used his connections to high value donors and other political campaigns to obtain additional funds for himself through fraudulent or otherwise questionable business dealings.

And he sustained all of this through a constant series of lies to his constituents, donors, and staff about his background and experience.

That’s the kind of thing that has his peers not wanting to wait for either his federal trial or the 2024 election to expel Santos. Fellow Republicans in New York, facing difficult elections next year, are particularly interested in voting against him.

Political handicappers think Santos’ district now leans toward Democrats.

It requires a two-thirds majority, or 290 of 435 lawmakers if everyone votes, to expel a member. Santos was expelled with a vote of 311 to 114, with 105 of his fellow Republicans voting in favor.

Who did the House not expel?

Back in 1838, Rep. William Graves of Kentucky killed a fellow member, Rep. Jonathan Cilley of Maine, in a duel. Despite an investigation, Graves was not even censured by the House, although Congress did outlaw the challenging or accepting of a duel in Washington, DC, as a result.

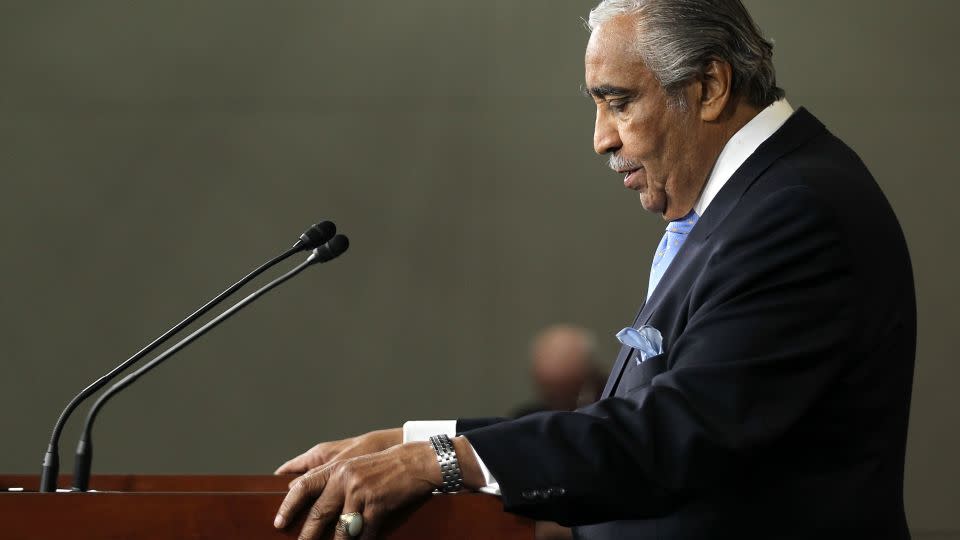

More recently, former Rep. Charles Rangel, a New York Democrat, endured a trial by the House Ethics Committee and was ultimately censured, but he was never in danger of being expelled.

He faced scrutiny for improperly raising funds for the Charles B. Rangel Center for Public Service, a City College of New York program that still bears his name, and for failing to pay all of his taxes even though he was in charge of the House tax writing committee. He continued to win reelection.

Another New York Democrat, former Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., never resigned, but his colleagues refused to seat him, a process known as exclusion, in 1967. Powell won the next election and the Supreme Court said he had to be seated.

William Jefferson, the Louisiana Democrat, was not expelled from the House even though the FBI found apparent bribe cash wrapped in foil and hidden in a pie crust box in his freezer. Voters kicked him out of office in the 2008 election. He was convicted in 2009 and sentenced to prison.

The resignation route

Resigning is always an option, particularly in conjunction with a guilty plea.

There have been multiple lawmakers in the past quarter century to leave the House in conjunction with a guilty plea or a conviction, including Randall “Duke” Cunningham and Duncan Hunter, California Republicans; Bob Ney, the Ohio Republican; Chris Collins, the New York Republican; and Jesse Jackson Jr., the Illinois Democrat who left before he was indicted.

The Senate process for expulsion is quite murky and no senator has actually been expelled since the Civil War. In 1995, Bob Packwood, the Oregon Republican accused of serial sexual harassment, came close to expulsion when the Senate Ethics Committee recommended his ouster. He resigned rather than suffer the indignity.

That’s the same path taken by Harrison Williams, the New Jersey Democrat convicted in the ABSCAM scandal.

Perhaps Sen. Bob Menendez will be the next test case. Menendez already survived one federal corruption trial and was reelected. Now up for reelection again, he is facing federal charges in a different corruption case. It’s not yet clear if Menendez will run for his seat in 2024 or not.

A Congressional Research Service examination of House and Senate expulsions tries, and fails, to find a consistent test for expulsion. Lawmakers, all of whom stand for election themselves, are loathe to tell voters they picked the wrong person.

Thus, CRS finds the debate around expulsion are competitions between “preserving the integrity of a given house versus the interest in preserving the results of a democratic election.”

This story has been updated with additional information.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com