Why it's been relatively easy to vaccinate against COVID-19 compared to HIV or cancer

Effective COVID-19 vaccines were developed in under a year. But a half-century after the country declared war on cancer, and 40 years after the first reported case of HIV/AIDS, there remains no way to prevent either disease, or many more.

Why? Biology and timing, scientists say.

How was it possible to develop effective COVID-19 vaccines in less than a year when after decades of trying there remains no way to prevent cancer or HIV/AIDS and many other deadly diseases?

COVID-19 and the virus that causes it were simply easier targets, according to a number of experts, and came along at a time when scientists well prepared to respond.

"COVID-19 can lead to very, very serious illness and can spread rapidly and therefore cause a global pandemic – but in terms of the immune system, it's actually kind of wimpy," said Dr. Dan Barouch, who helped develop Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine from his lab at Harvard University.

The human immune system can easily eliminate COVID-19, while none of the 38 million people infected with HIV over four decades has ever completely gotten rid of that virus on their own, said Barouch, who has been working on an HIV vaccine for more than 16 years.

"That virus has developed its own tricks to evade the immune system so the normal human body cannot eliminate it, and also it makes vaccine development very, very difficult," he said of HIV. "It's fundamental scientific differences."

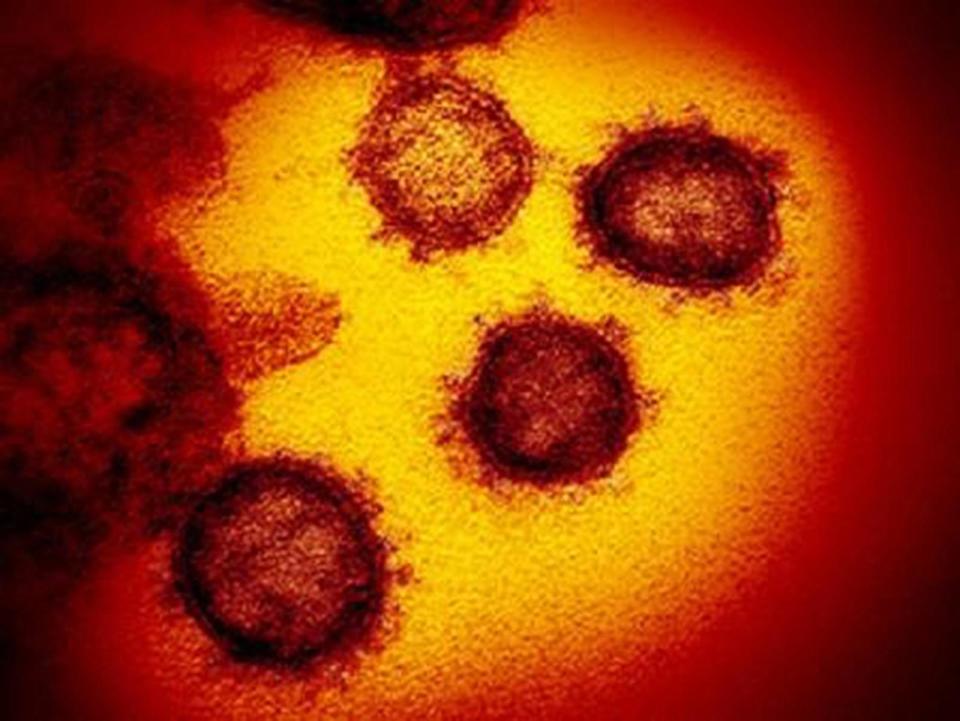

SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, is a pretty standard virus made of a single strand of genetic code and dotted on the outside with the spike protein that gives the coronavirus family of viruses its distinctive crowned profile.

The HIV virus, by contrast, has a smoother surface, said Dr. Roger Shapiro, an infectious disease clinician at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

"On the surface of HIV it's much more barren," he said, meaning it has fewer targets for vaccine developers to take aim.

And the targets HIV does have are shrouded from the immune system, Shapiro said.

While COVID- goes after certain cells that line the lungs, among other places, HIV attacks the immune system itself, he said. "The very cells that are meant to protect us are the ones targeted by HIV."

Plus, HIV mutates much faster.

"The variation we talk about in COVID is nothing compared to the variation we see with HIV," Shapiro said. Imagine all the variants people are worried about with COVID-19 and more happening within a single person.

So, unlike the spike protein on the SARS-CoV-2 virus, HIV lacks an obvious target for a vaccine, he said. And the targets it does have change rapidly and are hidden from the immune system.

Still, despite the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines, the world will probably never be able to eliminate the SARS-CoV-2 virus the way it has eliminated smallpox and has contained measles, Shapiro said.

More: How does COVID-19 end in the US? Likely with a death rate Americans are willing to 'accept'

Once someone is infected with or vaccinated against measles or smallpox, they're protected for life. But that's unlikely to happen with viruses like SARS-CoV-2, which is the same family as several common cold viruses that people can catch again and again.

With cancer, too, a key challenge has been what to target.

"The spike protein, for the most part, that's going to be the same for every single patient. For cancer, we know now that everyone's cancer is very very different," said Dr. David Braun, a kidney cancer specialist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Cancer is made up of cells that are nearly identical to cells of the body. That's why chemotherapy can be so devastating – because it can't tell the difference between healthy cells and cancerous ones and attacks both.

COVID-19 also came at a time when research – including for HIV and cancer – made it feasible to rapidly develop a vaccine, he and others said.

To deliver his HIV vaccine, Barouch spent years engineering a cold virus to carry a vaccine payload into cells without making people sick. He used the same modified adenovirus 26 to deliver his COVID-19 vaccine.

Researchers also learned from the first SARS virus and a related one called Middle East Respiratory virus how to target the spike protein.

And gene sequencing has become fast and cheap enough that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was quickly analyzed and its progress across the world and the variants that develop can be carefully tracked.

These scientific advances among others allowed scientists to develop COVID-19 vaccines in months rather than years. But people shouldn't forget or take for granted how lucky we are that the virus was so easily dealt with, said Dr. Daniel Griffin, chief of the division of infectious disease at ProHEALTH, a health care provider in New York.

"The idea of vaccines that are 100% or near-abouts at keeping people from dying and in the 90s at keeping you from getting infected," he said, "this is a whole new paradigm for vaccine efficacy."

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Science behind COVID vaccine: Why created faster than HIV, cancer cure