Why Rugby, a historic Tennessee site, flourished and floundered

Carolyn Krause brings us a two-part series on Historic Rugby, the utopian community originally built in 1880 for more than 300 British immigrants and Americans in the wilderness of East Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. The series is based partly on the perspective of Fred Bailey, retired professor of history at Abilene Christian University and a published author of articles and books. He has been teaching courses on Queen Victoria’s England at the Oak Ridge Institute for Continued Learning, or ORICL, at Roane State Community College’s Oak Ridge campus.

Many Oak Ridgers have visited Historic Rugby and some of its original 65 to 70 buildings of Victorian design. Even though the town declined between 1890 and 1900, Rugby today is both a living community surrounded by rugged river gorges and historic trails and a fascinating public historic site run by Historic Rugby. Visitors are offered a museum, historic building tours, lodging, stores, and an events center. Open to the public since 1966 as a nonprofit 501(c)3 site, Rugby is recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Visit www.historicrugby.org for information on upcoming events. Enjoy Carolyn’s story about Rugby.

***

Thomas Hughes (1822-96) was a distinguished British citizen who had a vision for a utopian town he wanted to build in rural East Tennessee. He chose to name it Rugby after the school he attended for eight years. A better athlete than student, he played cricket and rugby, the sport that was invented at his alma mater.

Hughes was an English lawyer, judge, politician and author of the popular and immensely influential children’s book “Tom Brown’s School Days” (1857). The second son of John Hughes, he conceived of the town partly as a farming community for the younger sons of English gentry.

According to the Historic Rugby website, “Under the custom of primogeniture, the eldest son usually inherited everything, leaving the younger sons with only a few socially accepted occupations in England or its empire. In America, Hughes believed, these young men’s energies and talents could be directed toward community building through agriculture. The townsite and surrounding lands were chosen partly because the newly built Cincinnati-Southern Railroad had just completed a significant line to Chattanooga, opening up this part of the Cumberland Plateau.”

Hughes wanted to give the young British men useful tasks to perform as well as recreational opportunities, such as playing cricket and rugby, to make their bodies strong and healthy and to create the spirit of teamwork. He envisioned this model community as a shining city on the plateau and as a cooperative enterprise that reflected “a cultured, Christian lifestyle, free of the rigid class distinctions of Britain,” according to the Historic Rugby website.

According to Fred Bailey, a retired history professor who gave a lecture on the history of Rugby, Tenn., to an ORICL class, Rugby was one of the 2,000 some utopian communities that sprang up in the 19th century in the United States. A utopian community has been defined as “a group of people who are attempting to establish a new social pattern based upon a vision of the ideal society and who have withdrawn themselves from the community at large to embody their religious or secular vision in experimental form.”

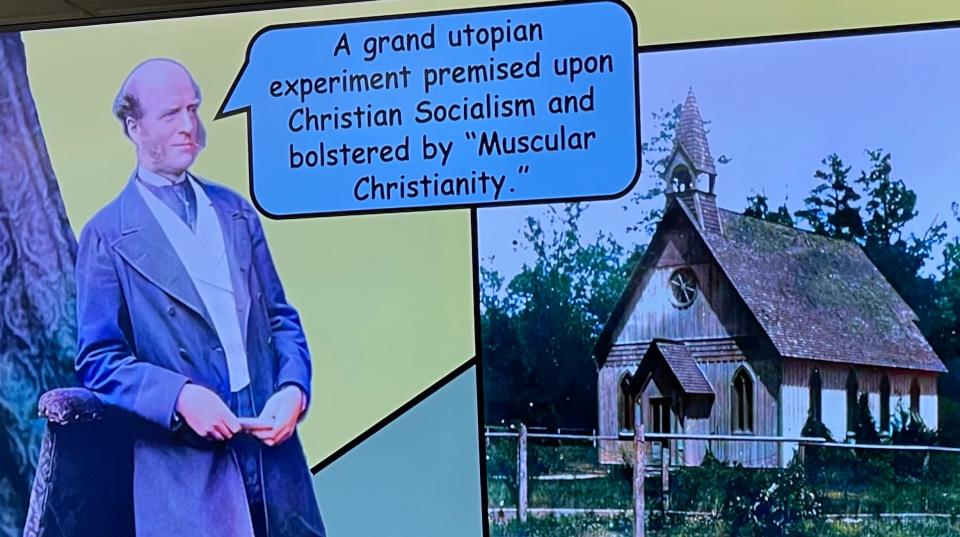

What was Hughes’ vision of an ideal society? Bailey said that Hughes saw the Rugby community as “a grand utopian experiment premised upon Christian socialism and bolstered by muscular Christianity.” These movements that were embraced by Hughes and that will be addressed in the second part of this series, provided a religious rationale for action to address social injustices believed to be caused by the perceived sins of capitalism, industrialization and warmongering.

In October 1880, Hughes gave a speech almost an hour long at the dedication of the new community of Rugby. According to Bailey, the core of what Hughes had to say was this: “We’re about to open a town here to create a new center of human life in this strangely beautiful solitude center in which, as we trust, healthy, hopeful, reverent or in one word ‘godly’ life shall grow up from the first, and shall spread itself, so we hope, over all the neighboring regions of the southern highlands.”

“The Rugby colonists,” Bailey added, “were trying to raise vegetables for sale and then haul them eight miles to the nearest railroad where they would either be shipped northward to Cincinnati or southward to Chattanooga.” It was hoped that their agricultural pursuits would make the residents prosperous and enable the community to grow.

According to the Historic Rugby website, the utopian community “both flourished and floundered in the 1880s, attracting widespread attention on two continents and hundreds of hopeful settlers from both Britain and other parts of America. By 1884, Hughes’ vision seemed close to becoming a thriving reality.

“An English agriculturalist had been employed to help train new colonists. Some 65-70 graceful Victorian buildings had been constructed on the townsite, and over 300 residents enjoyed the rustic yet culturally refined atmosphere of this ‘New Jerusalem.’

“Literary societies and drama clubs were established. The grand Tabard Inn soon became the social center of the colony. The Thomas Hughes Public Library, with some 7,000 volumes donated by admirers and publishers, was the pride of the colony. Rugby printed its own weekly newspaper. General stores, stables, sawmills, boarding houses, a drug store, dairy and butcher shop were all in operation.”

Bailey mentioned some problems that helped lead to the departure of many colonists by the turn of the century. People disagreed about land titles, raising questions about who originally owned the land and who had a legal claim to land grants or purchases. The land was not as fertile as government pamphlets had maintained. The second sons of the British gentry did not know how to farm. The tomatoes being grown were low in quality and eventually quantity as a drought caused the tomato plants to shrivel up and die.

According to the Historic Rugby website, a typhoid epidemic in 1881 and two inn fires in 1884 and 1889 were among the disasters that plagued the community. “Hughes – whose aged mother Margaret Hughes, brother Hastings and niece Emily lived in Rugby during its early years – managed to spend only a month or so each year in the colony. But he poured more than $75,000 of his own money into the effort to build the community in the wilderness.

“Despite the problems, Hughes never gave up on Rugby’s future. In a letter to some of the remaining settlers shortly before he died in 1896, Hughes wrote poignantly: ‘I can’t help feeling and believing that good seed was sown when Rugby was founded and someday the reapers, whoever they may be, will come along with joy bearing heavy sheaves with them.’”

Hughes’ legacy included five sons and four daughters. Bailey noted that the oldest daughter, Lilian, perished in the sinking of the RMS Titanic ship in 1912.

***

Next: Carolyn Krause will present information on the philosophy, writings and British Christian movements embraced by Thomas Hughes, founder of Rugby, Tenn., including the movement that became known in our nation as the social gospel movement.

Caption: Thomas Hughes.jpg: Thomas Hughes. Wikipedia

Caption: Fred Bailey artistic slide.jpg Fred Bailey’s artistic slide on Thomas Hughes’ vision for Rugby, Tenn. Provided by Fred Bailey

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Why Rugby, a historic Tennessee site, flourished and floundered