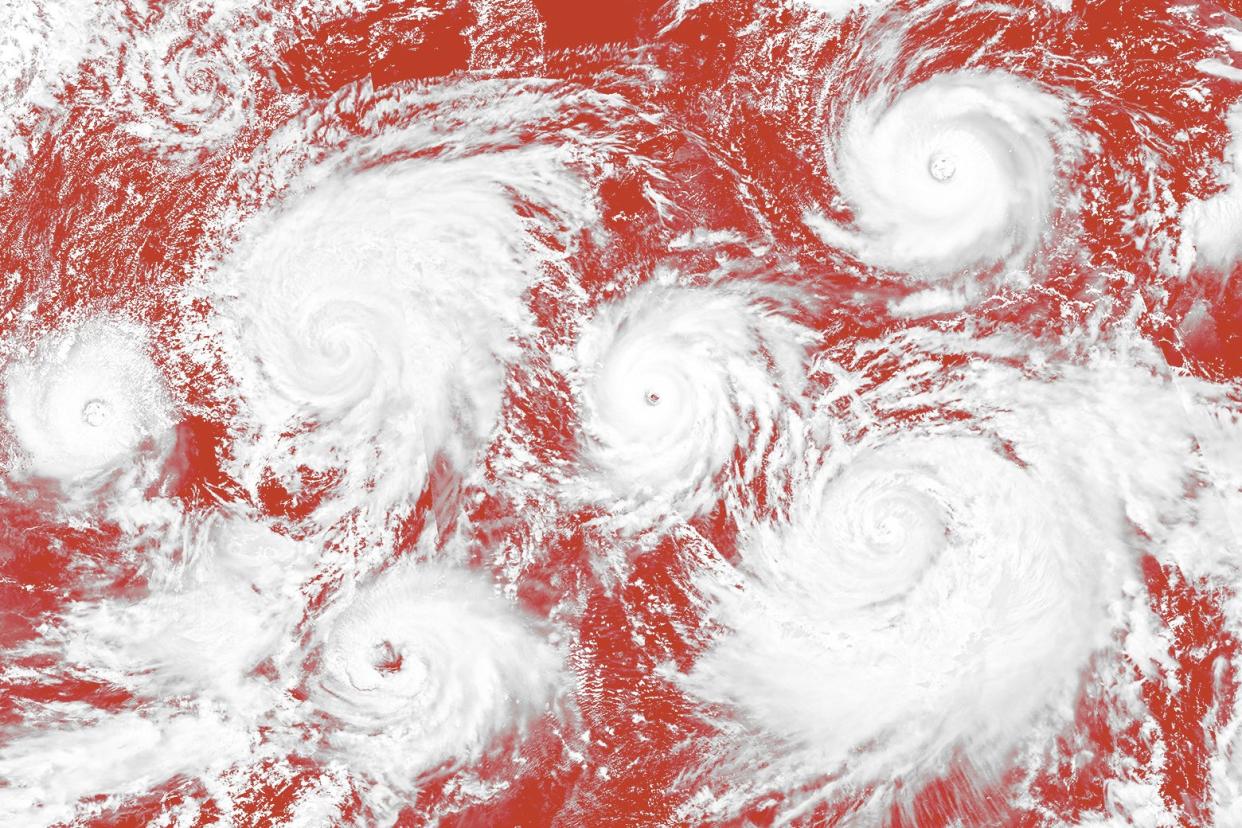

How a “Marine Heatwave” Is Creating a More Chaotic Hurricane Season

On Monday, Hurricane Franklin, which became a Category 4 hurricane near Bermuda, began creating “life-threatening surf and rip currents” along the East Coast. Now, on Tuesday, just southwest of Hurricane Franklin, Tropical Storm Idalia has strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane and is expected to make landfall in Florida on Wednesday.

The storms mark an unusually busy Atlantic hurricane season that hasn’t even hit its peak yet—the U.S. could see as many as 21 named storms this year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Hurricane Idalia is the ninth storm of this current hurricane season (a six-month period that runs from June 1 until Nov. 30) and has meteorologists seriously concerned. Idalia is expected to become a Category 3 hurricane and tear trees down, block roads, and cause power outages. It could even end up hitting parts of Florida that aren’t normally hit by storms. The state has already shut down schools and a major airport and called on residents across at least 22 counties to evacuate—including the cities of Tampa and Orlando.

“It’s not unprecedented, but it’s unusual to have two Categories 3 or higher in August,” said David Robinson, climatologist at Rutgers University. “All of a sudden, things have really ramped up.”

NOAA initially predicted that this year’s hurricane season would be “near normal,” with about 12 to 17 named storms expected, of which five to nine could turn into hurricanes. Then, in early August, the agency released a revised prediction that upped the ante: The ongoing 2023 Atlantic hurricane season is now expected to be “above normal,” with 14 to 21 named storms, of which six to 11 could become hurricanes.

What drove that revised prediction? A few factors, but one of the most significant is the current record-breaking ocean temperatures. In fact, the ocean has gotten so hot it’s forced climate researchers to coin the term “marine heat wave” because the North Atlantic has seen increasingly warmer temperatures every day since late March. The Gulf of Mexico, which is usually around 86 degrees Fahrenheit, has been 87 to 88 degrees. That’s about 2.5 degrees above average, which may not seem like a whole lot, but even slight fluctuations in ocean temperatures can cause extreme weather changes. Robinson also noted there’s been record-high ocean temperatures in the Caribbean and western Atlantic. And right now, that’s translating to an especially chaotic hurricane season.

“As a hurricane intensifies, it stirs up a lot of water, and it usually stirs up cold water from below very easily,” said Bob Henson, a journalist and meteorologist with Yale Climate Connections. “But if it’s passing over an area where there’s warm water down to 100 feet, it’s less likely to stir up cold water that would inhibit its growth.” In the current case of Hurricane Idalia, Henson is concerned it’ll gain even more energy from the ocean’s hot temperatures, resulting in a more severe storm and serious damage to Florida.

And what’s causing the ocean to be so hot? Climate change is one glaring reason, because “in a warming world, you’re going to have warmer oceans,” explained Henson. But climate change isn’t the only contributing factor, because ocean temperatures do fluctuate naturally over time.

Another interesting phenomenon at play is the current El Niño season that we’re experiencing. That’s a natural climate pattern that produces weaker surface winds across the entire tropical Pacific and pushes ocean temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean to be warmer than average—which is what likely drove Hurricane Hilary, which hit the West Coast just a week ago. And because the Pacific waters warm up during an El Niño season, the Atlantic region is expected to cool down and actually inhibit hurricanes.

But the Atlantic waters are so hot right now that El Niño’s inhibiting effects are being stifled. “So what do you conclude when you have one factor, like the warm waters, saying it will be a very busy season, and a pretty strong El Niño saying it’s actually a quiet season?” said Henson. “It’s hard to know which of those is going to win out.”

Henson believes it boils down to both factors creating a unique hurricane season. “Oceans warm some years, and we’re going to see spikes,” said Henson. “And it’s just one of those years where the long-term warming trend in oceans driven by climate change is making itself known.”

And it’s definitely been one of those years, with nine named storms already appearing before hurricane season has hit its midway point. Some of these tropical storms never hit landfall or gained enough traction to turn into a hurricane, but nonetheless created wind speeds of 39 mph, enough to merit getting named—a tropical storm turns into a hurricane when wind speeds rise over 74 mph. A hurricane’s wind speed is what determines its category, and those in Category 3, 4, and 5 are considered major hurricanes. But Category 1 and 2 hurricanes are still serious; they can blow shingles off of roofs, uproot trees, and cause power outages. In some ways, slower storms can actually be more destructive because they can drop rain on the same area for hours or days on end, leading to potentially deadly flooding.

As of Tuesday morning, Hurricane Idalia was clocking in at Category 1, but meteorologists expect it to turn into a Category 3 by Wednesday as it touches down in Florida. That comes with winds between 111 and 129 mph—Hurricane Katrina, which hit Florida in 2005, was a Category 3 storm.

As for the remaining three months of hurricane season, it’s impossible to predict exactly what will happen. Meteorologists can typically only issue predictions about a week to 10 days out, but since it’s an El Niño season, the storms should follow a familiar pattern. As hurricane season continues, Henson said, the inhibiting effects of El Niño will get stronger, creating less chance of there being a high number of storms in the last several weeks of the season. But there’s a catch: “If that El Niño effect wanes just for a week or so, the waters may still be very warm, so we can’t rule out a very strong storm even in October, November,” said Henson.

“Just like someone running a fever, it may spike one hour and then decrease the next hour,” he said. “You can’t say the fever will spike at 10 a.m. or noon or 2 p.m., but you can expect there will be a spike at some point.”