Why we shouldn’t censor Dr. Seuss: Parents and their children are wise

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1951, children’s author Jerrold Beim published a short book called "The Swimming Hole." It described two groups of boys — one white, one Black — who frolic together in the water. Refusing to swim with the Black boys, a white kid receives a nasty sunburn and — eventually — a stern rebuke from his peers. “Suppose we would refuse to play with you now because your face is red?” they ask him.

"The Swimming Hole" sparked outrage across the segregated South, where it was frequently banned from schools. So was "The Rabbits’ Wedding" — which described the nuptials of a Black hare and a white one — and even a new edition of "The Three Little Pigs." The revised edition portrayed a Black pig as better than a white one, which offended the delicate sensibilities of white people below the Mason-Dixon line.

Censors wipe out whole pieces of literature

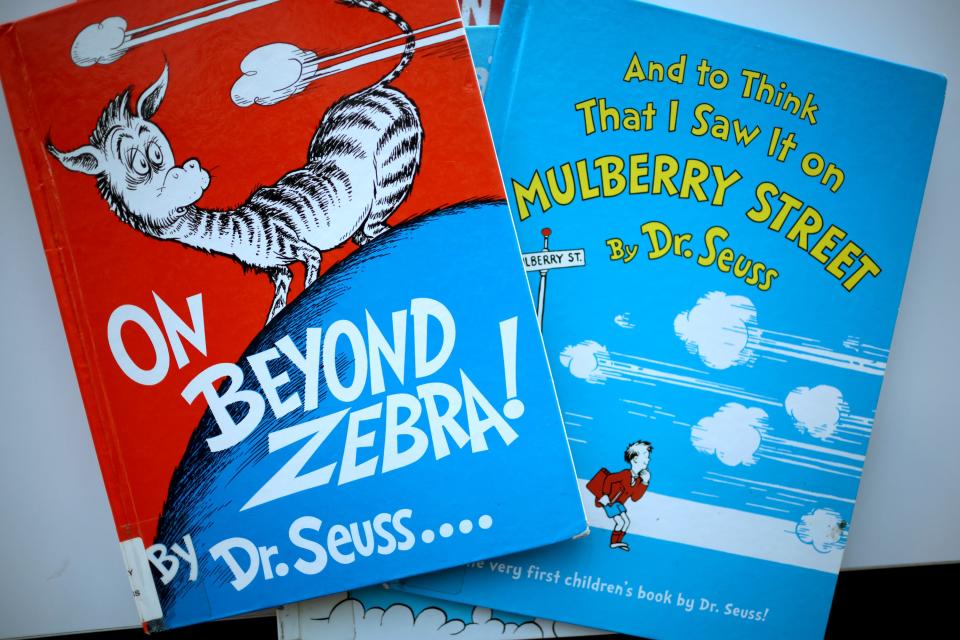

I’ve been thinking about this history during the recent debate over Dr. Seuss, born Theodor Seuss Geisel. Recently, the company that oversees his estate announced that it would end publication and licensing of six books by Dr. Seuss that “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.”

But it’s hurtful to remove them from the public square, which is the goal of censors everywhere. They think we can't recognize the "problematic" aspects of Dr. Seuss, so we must be shielded from him. And they're wrong about that.

Yes, his books include blatantly racist caricatures and stereotypes: an Asian person holding chopsticks, barefooted Africans wearing grass skirts, and so on. Before he died in 1991, Seuss actually altered some of the drawings to make them less objectionable. In the Asian illustration, for example, he removed the figure’s pigtail, changed its yellow skin tone, and altered the accompanying text to read “Chinese” instead of “Chinaman.”

But the illustration still offends, which raises an obvious question: why didn’t the publishers alter it again or simply remove it? We don’t know, but we can guess the answer: to satiate Dr. Seuss’ critics. Censors don’t aim to strike a word here, and a picture there; they want to obliterate a work of literature altogether, so nobody sees it.

Shaquille O’Neal and Rey Saldaña: 3 million kids missing from school because of COVID-19

And that never works in America, where authors often become more popular when someone tries to shut them down. A few days after the announcement that six Dr. Seuss books would no longer be published, four of them shot into Amazon’s list of top 20 best-sellers. All told, 13 of the 20 books were by — you guessed it — Dr. Seuss.

Americans don't want to be told what they can and can't read

The moral of the story? Americans don’t want to be told what they can and can’t read. And, most of all, they want to make up their own minds instead of letting someone else do it for them.

That’s the deepest fear of the censor, in all times and places: that readers will get the wrong idea. In the segregated South, whites worried that kids who encountered The Swimming Hole would decide that racism was wrong. And now there’s a fear that children who read Dr. Seuss will become racists themselves.

But children — and their parents — are wiser than that. Writing last year, African-American blogger Danielle Slaughter argued that Dr. Seuss — her young son's favorite author—would help her teach him about racism. Dr. Seuss wrote books that indicted discrimination (most famously, "The Sneetches") but he also engaged in his own forms of it, Slaughter noted. It was complicated. And so is America, especially when it comes to race.

“Choosing to throw away his books doesn’t make you any less racist,” Slaughter wrote, explaining why she continued to read Dr. Seuss with her family. “It does, however, make you the type of person who insists on talking about racism in hushed tones.”

The real question is whether we trust each other enough to have that talk out loud. Last week, the children’s author Deborah Hautzig acknowledged the racism in Dr. Seuss’ books but insisted that they should remain available to everyone. Hautzig recalled that her first novel, "Hey, Dollface," was banned in schools and libraries across the South when it appeared in 1978 because of its frank exploration of teenage female sexuality.

Amid death, grief and COVID: Passing on my mother's gift of resiliency to my daughter

“Children are smart,” Hautzig wrote. “They have every right to see, examine, challenge, and reject racism for themselves, and to have it pointed out and vehemently rejected by the adults who read to them.”

No matter its source or its goal, censorship always betrays a lack of faith in human beings. We don't have to tuck Dr. Seuss away in a corner. We can talk about him, the good and the bad: his light spirit of whimsy, and the dark racism that marred it. We are better than the censors think we are.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches education and history at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the co-author (with Signe Wilkinson) of “Free Speech, and Why You Should Give a Damn,” which will be published next month by City of Light Press.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Don't cancel Dr. Seuss. Trust his readers instead.