Why a Soviet spy in Oak Ridge was never arrested or recognized

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

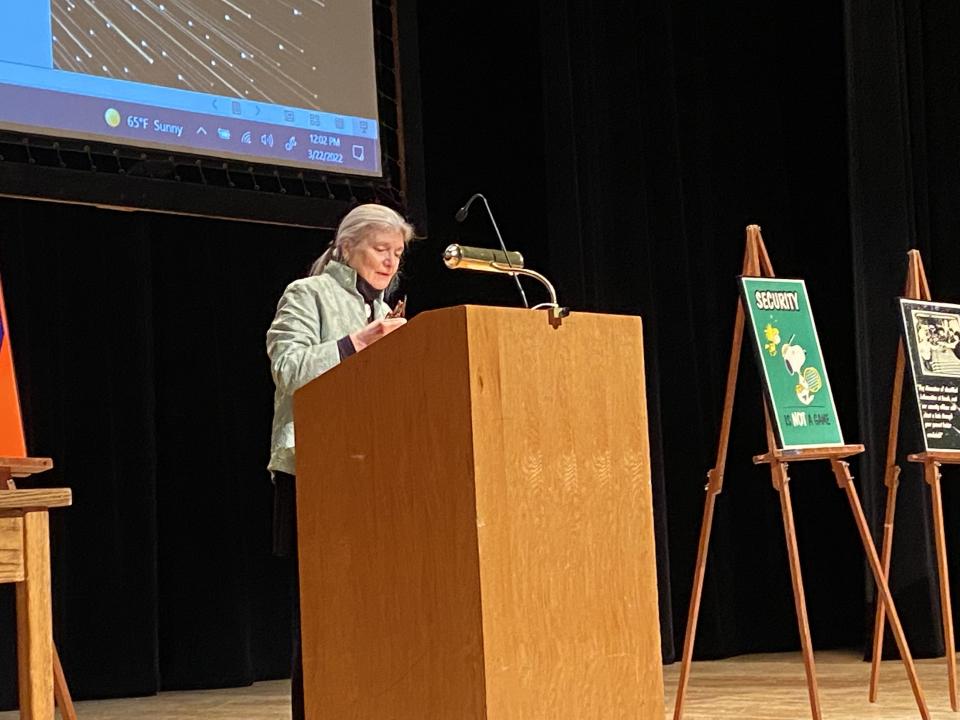

Here is Carolyn Krause’s second and final column in the series on Ann Hagedorn’s “Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy in America Who Got Away.” The book is about an American-born Soviet spy who worked for the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge from Aug. 11, 1944, through June 1945. Hagedorn was the keynote speaker at the annual Lunch 4 Literacy event on March 22, 2022, in Oak Ridge.

***

On Aug. 29, 1949, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, three years after building its first nuclear reactor. Its successful nuclear weapons test occurred only four years after the U.S. team led by Los Alamos laboratory director J. Robert Oppenheimer exploded the Trinity bomb of July 1945 in the New Mexico desert. The American and Soviet nuclear tests were both plutonium-based bombs with a beryllium-polonium initiator to kick-start the neutron chain reaction that triggered the radioactive explosion.

Defense experts in the United States and Europe were surprised that the Soviets had developed the A-bomb so fast. They attributed the Communist nation’s success, Hagedorn wrote, “to the mix of Soviet scientific prowess and information relayed by Soviet spy networks in the West.”

After World War II, several American, Canadian and British citizens, as well as Soviet citizens, were outed as Soviet spies by Soviet defectors, and the FBI began investigating. Some alleged spies, such as British physicist Klaus Fuchs, were arrested, put on trial and imprisoned, and others like the Americans, Julian and Ethel Rosenberg, were arrested, tried and executed.

According to Hagedorn, Fuchs and Julian Rosenberg “channeled U.S. atomic bomb secrets to Russia for the sake of world peace.” They thought peace could be maintained only if the world had at least two nuclear superpowers, who would resist launching nuclear attacks because of the doctrine of “mutual assured destruction.”

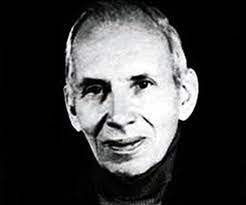

World peace was not apparently the primary motivation for George Koval to become a spy, according to Hagedorn. The Iowa-born scientist with Russian Jewish heritage agreed to be trained to serve as a Soviet spy (with the code name Agent Delmar) in the United States to learn about its chemical weapons research. He carried out his mission when U.S. Army officials assigned him to work as a health physicist in Oak Ridge and Dayton, Ohio, in 1944 and 1945. Koval, who was never arrested in America for his atomic spying, willingly received espionage training while in Moscow in 1939. The reason: the political situation under Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin placed Koval’s wife in danger.

In October 1936, Koval married Lyudmila (Mila) Ivanova, a classmate of his at the Mendeleev Chemical Institute. The following year Stalin started the Great Purge during which at least 18 million adults and children, considered to be Stalin’s political opponents, were sent to gulags where many died from overwork, starvation, exposure or diseases. Mila was in danger of being sent to a Soviet labor camp because her father was a landowning aristocrat and had been in a high position in the Red Army, founded by Leon Trotsky, an enemy of Stalin who exiled him in 1929.

“Fortunately, Koval was a good candidate for Soviet intelligence work and could fill a vacancy resulting from Red Army purges,” Hagedorn wrote. “George could be a good Russian spy in the United States because he spoke fluent English without a Russian accent and knew the American culture. In the spring of 1939, he was brought into the Soviet military intelligence department known as GRU.” Koval, 26, concluded correctly that his loyalty to Stalin would protect Mila.

“Mila and her mother got special treatment because of Koval’s spying job,” Hagedorn wrote. “They were given an apartment and Mila was sent to work at a chemical factory that made explosives from the residuals of oil processing. It was a toxic workplace, and because of the hard work and harsh 1941 winter, Mila was hospitalized for a respiratory condition from which she apparently would never fully recover. Because of the factory’s toxicity, she could not have children.”

Koval was told that his espionage assignment in America would last only two years; in fact, he was away from Mila for eight years. He delivered his reports on the Oak Ridge work to his handlers by taking a week-long leave of absence to travel to New York and by meeting with a mysterious visitor to Oak Ridge named Clyde.

In Dayton, Ohio, he was offered a permanent health physics job by Monsanto Chemical Corp., the government contractor for the polonium work, but he wisely declined the job. About the same time in 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a GRU intelligence officer at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, Canada, defected and released documents “outing Soviet spies in Canada, Britain, and the United States, including those connected to atomic bomb espionage.”

Koval was not exposed but had reason to be worried.

“Now his plan must be to try to keep a low profile, request his return to Moscow and, while waiting for orders, avoid detection,” Hagedorn wrote, adding that he “evaded detection by avoiding connections with spy networks and the Communist party but joining and leading regular American clubs.” In 1947, 10 defendants accused of being Soviet spies and discovered in 1945 were convicted and sentenced to prison.

In September 1948, the New York Times published articles with the headlines “Atom Bomb Leaks Hinted by Groves” and “Russians Got Data on Bomb,” and TIME magazine’s issue on Oct. 4 had a cover story on “The Atomic Spy Hunt.” On Oct. 7, Koval boarded the SS America ship headed for Le Havre, France, and made his way by train to Moscow. There he faced anti-American propaganda and anti-Semitism, preventing him from rising to a high GRU post and from receiving minor recognition. Wrote Hagedorn: “To be sure, his work during the war would become an enduring secret.”

According to Hagedorn, Koval’s anonymous reports between 1944 and 1946 to Operation Enormoz helped Igor Kurchatov, the Soviet Union’s atomic project scientific director, decide to study plutonium fission in an implosion-designed bomb (first developed at Los Alamos after examining Oak Ridge-produced plutonium), and showed the advantages of making polonium by using reactor-produced bismuth instead of the lower-productivity lead dioxide process. One report included a diagram of the X-10 pile (Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Graphite Reactor).

On July 19, 1954, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who had called Soviet atomic espionage “the crime of the century,” ordered an investigation of the location and employment of George Koval, six years after he left the U.S. The FBI wanted to extradite him and charge him with treason but couldn’t after receiving his 1959 letter stating, “I have been a citizen of the USSR since 1932.”

After earning his Ph.D. at the Mendeleev Institute (now the Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology), Koval became an esteemed professor in its department of chemical technology for 35 years, starting in 1949. He died in January 2006 at the age of 92. There was no obituary.

In early 2007, Russian President Vladimir Putin visited a new exhibition of Cold War spies in the country’s new Military Intelligence Directorate. He saw a portrait of George Abramovich Koval and asked for information on his work.

On Nov. 2, 2007, at Novo-Ogaryovo, Putin’s estate on the outskirts of Moscow, Putin bestowed Koval with Russia’s highest civilian honor, the Hero of the Russian Federation gold medal, for his role in the making of the first Soviet atomic bomb.

In presenting Koval’s posthumous award to Russia’s defense minister, Putin proclaimed that Koval was “the only Soviet intelligence officer to penetrate the U.S. secret atomic facilities producing the plutonium, enriched uranium and polonium used to create the atomic bomb.” The Russian president added that the American secrets he sent to Moscow “helped speed up considerably the time it took for the Soviet Union to develop an atomic bomb of its own, thus ensuring the preservation of strategic military parity with the United States.”

“Few people knew about Koval’s intriguing double life,” Hagedorn concluded. “Because he was skilled enough never to be caught in America and because he was hit hard by the politics of prejudice upon his return to the Soviet Union, his story went unnoticed in the history of both nations.” While he was alive, he was an unknown traitor here and an unsung hero there.

***

Thank you Carolyn for capturing the intrigue associated with George Koval as researched, published and presented by Ann Hagedorn to a large Oak Ridge audience in the Oak Ridge High School auditorium for the Lunch 4 Literacy event this year.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Why a Soviet spy in Oak Ridge was never arrested or recognized