Why ‘the supremacy of the two states’ lies in the score of a Carolina football game

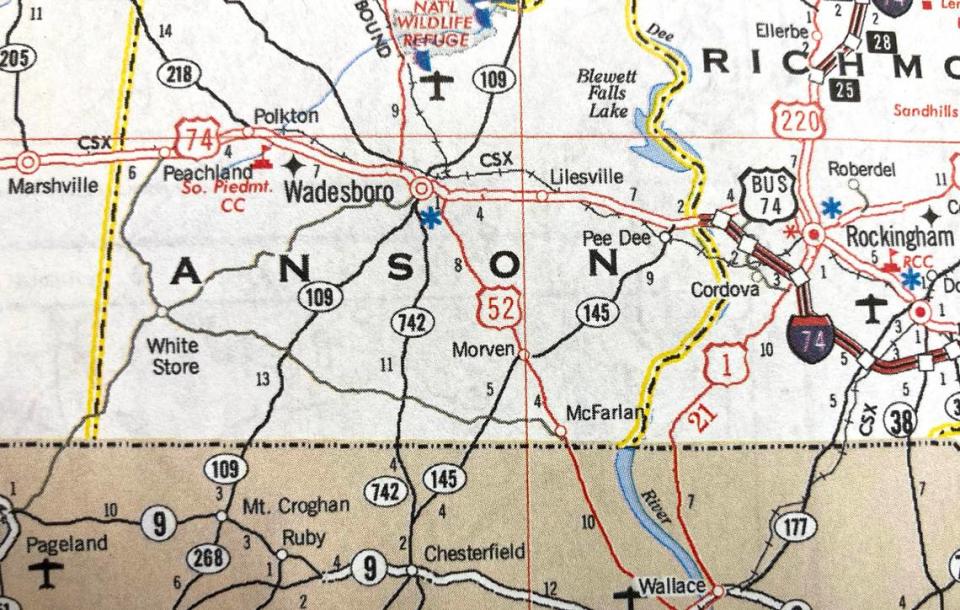

This old textile town of about 5,000 in Anson County, not far from the Pee Dee River, is the exact midpoint of two Carolinas; close enough to the center of Carolina, itself, however the word is defined. There’s nothing here to suggest its place. Nothing to let anyone know this town is at the center of a spectrum — light blue on one end; garnet and black on the other.

About 86 miles on a straight line to the northeast is one of those Carolinas, the one that resides in Chapel Hill. The University of North Carolina. And about 86 miles to the southwest is the other of those Carolinas, the one in Columbia, S.C. The University of South Carolina. Their football teams meet again on Saturday, in Charlotte. Carolina vs. Carolina, for the 60th time.

Here in the midpoint on a recent Thursday afternoon was a scene perhaps befitting of small-town Carolina, North or South or any other direction. Two Dollar Generals bookended Highway 74 on either side of Wadesboro. Downtown, near the courthouse square, some mom-and-pops remained open alongside others long shuttered. It all had the look of a place trying to hang on.

A little ways south of town, just past the Wadesboro IGA, Greene Street turns back into state highway 109. The two-lane road meanders past a small elementary school and Baptist churches, between two cemeteries and through a forest canopy and on down to the state line.

Follow that line about 123 miles left, to the east, and you’ll wind up just north of Little River and just south of Sunset Beach, on Bird Island. Follow the border 211 miles in the other direction, as difficult as it might be while the land rises in hills, and then mountains, and you’ll wind up in the middle of the Chattooga River, near a three-way intersection with Georgia.

The state line extends 334 miles through 26 counties, 15 in North Carolina and 11 in South Carolina. It cuts through farmland and forests, big rivers and little creeks, narrow country roads and interstates. It runs just north of South of the Border, the kitschy tourist trap that has somehow persevered, and just south of Tabor City, one of several small North Carolina border towns. Against all odds, the state line does not bisect a single barbecue restaurant — perhaps because of some unknown accord to preserve peace between loyalists of sauce based in vinegar or mustard.

Come Sept. 2, some 60,000 people, maybe more, will gather in Charlotte, at Bank of America Stadium, to watch the Tar Heels and Gamecocks. It will be part football game — and an important one at that for the aspirations of both teams — but also part family reunion among close relatives and distant cousins, literal and metaphorical, united by a land they call home. And like any good family reunion, there’ll be drama and fighting and unkind words, with a lot of the angst — maybe just about all of it — rooted in one age-old debate: Which really is the rightful Carolina, anyway?

What’s in a name?

The word itself derives from the name Charles, and England’s King Charles I, in particular. He was the one, back in the first half of the 1600s, who allowed his men to explore and begin settling the southern half of North America. Just south of present-day Virginia, throughout a region that Spain had abandoned, a land called Carolana was born, in homage to the Latin form of Charles.

It wasn’t until the 1660s, under King Charles II, that Carolina (as it was now known) came to establish its first boundaries. They stretched south to what’s now the Florida-Georgia line, near St. Augustine, and west to the Pacific Ocean, though nobody knew then how far away that was. Carolina’s earliest leaders and settlers were nothing if not ambitious, or maybe a little delusional.

Carolina was united, for a while, or at least as united as an early colonial settlement could be. Accounts in the books “North Carolina: A History,” and “The Tar Heel State” detail the political in-fighting and uprisings and the regular wars with Native Americans, one of which, against the Tuscora, nearly wiped out the northern part of the settlement in 1711.

By 1712, Carolina split in two, North and South, setting both on their course for the next 150 years. South Carolina, thanks to its slavery-fueled cotton empire and Charleston’s rise as arguably the most important and cosmopolitan city in this new America, became a place of vast wealth and aristocracy. North Carolina, by comparison, was an uncivilized backwater, especially in its earliest days; a land of pork-eating people “so intolerably lazy,” as William Byrd, a Virginian, wrote in 1728 in “The History of The Dividing Line.”

Before North Carolinians become offended, consider Byrd might’ve known what he was talking about. In the same book he wrote, of the northern Carolina: “The only business here is raising of hogs, which is managed with the least trouble, and affords the diet they are most fond of. The truth of it is, the inhabitants of North Carolina devour so much swine’s flesh, that it fills them full of gross humours.”

Well, the truth hurts and the more things change ... and, anyway, barbecue had to start somewhere.

For about 150 years or so, the dominant Carolina — the one with the most rightful claim to the name, or at least the most power to commandeer it — was the one to the south. In terms economic and cultural, and due largely to geography and ease of settlement and trade, South Carolina thrived in a way North Carolina didn’t, or couldn’t. In those years even the academic prowess of the University of North Carolina, the nation’s first public university, paled in comparison to that of the University of South Carolina, said Matt Simmons, a North Carolina native who’s the assistant director for the University of South Carolina’s Institute for Southern Studies.

And then, the Civil War. South Carolina seceded first, and arguably suffered the most toward the end of the Union’s victory. North Carolina was the last state to secede, and arguably the one whose betrayal was least punished. The fortunes of the Carolinas began to change.

Same, but different

If North and South had remained as one big, unified Carolina, that state would rank 13th nationally in land area, just ahead of Utah and just behind Minnesota. The state of Carolina would be the fifth-most populated in the country and first in rural population, with more than 5.1 million residents in non-urban areas, according to the U.S. Census. On its own, North Carolina’s rural population (3.5 million, as of 2020) ranks second nationally, behind Texas.

Instead we have a region united by its similarities as much as its differences; a land where one of our favorite pastimes is to look down on the other as inferior, regardless of whether the judgment is based in reality. Still, there can be no denying that to the majority of people, especially outside of South Carolina or those native to it, the word “Carolina” carries one specific connotation, or maybe two: either the university in Chapel Hill or the state it calls home.

We can credit this truth — or place blame, depending on one’s perspective — to either Dean Smith or James Taylor or Michael Jordan or perhaps all three, among other culprits. For it was Smith, first, and then Jordan, who arguably most helped the Tar Heels of North Carolina to become a national collegiate athletics brand, one so popular and visible that, like a pop star who reaches a certain level of fame, a full name is no longer required. And it was Taylor whose Chapel Hill roots and longing for home inspired what became the unofficial anthem of North Carolina.

In my mind, I’m going to Carolina

Can’t you see the sunshine?

Can’t you just feel the moonshine?

With respect to those from Daufuskie Island to Greenville, and throughout the Low Country and up into the Upstate, Taylor wasn’t referencing anywhere south of the border. And yet there, too, is an ownership of the moniker and a pride in it. In Columbia alone are enough businesses and Carolina spirit to suggest that South Carolina has as much a claim to the single identifier as anyone to the north, whether Down East or in the Piedmont or up in the High Country.

Near the USC campus — and that’s for another story, the eternal battle with the University of Southern California over the right to that acronym — there’s no shortage of Carolina things. The Carolina Barbershop. The Carolina Coliseum. The Carolina Cafe, which is not to be confused with Raleigh’s Cafe Carolina (the Chapel Hill location closed during the pandemic).

Chapel Hill has its own establishments named in honor of King Charles I, or at least after the state his name inspired. The Carolina Inn, on the edge of UNC’s campus. The Carolina Brewery, which was the Triangle’s first to produce craft beer. The Carolina Coffee Shop, which isn’t a coffee shop at all but the oldest surviving restaurant on Franklin Street. In Chapel Hill, too, there’s Top of the Hill, the popular restaurant and brewery.

In Columbia, right there on South Carolina’s campus, is the Top of Carolina restaurant. And if we’re being honest, a hill is no match for a region, as far as names go. All these Carolinas, in separate Carolinas, can create a little confusion. Folks in the Dakotas might be able to empathize, if their states had been around as long as ours. As it is, people in the Carolinas bear a unique burden, or maybe it’s a talent. We know what Carolina really means even if it means something completely different somewhere else.

BBQ and beaches

Among our differences in culture and economic fortune and politics and history, at least Carolinians, North and South, can make room for some universally agreed-upon truths. Our beaches are difficult to beat, for one. Combine them with the mountains and that’s a one-two punch that most of the other 48 states would have difficulty matching.

The barbecue here in this part of the Carolinas, wherever it might be, is a lot better than it is over there in that part of the Carolinas, wherever that might be. Another commonality, at least among the flagship Carolinas in their respective states: a longing to be more relevant in the one sport that now most dominates college athletics, and the shared misery in pursuit of such elusive excellence.

North Carolina’s last conference championship in football came in 1980. Which perhaps isn’t so bad considering South Carolina’s most recent conference championship in football came in 1969, about a year and a half before it withdrew from the ACC in 1971. Both schools have flirted with sustained football success before circumstances intervened. Mack Brown’s first tenure in Chapel Hill ending with him leaving for Texas. Steve Spurrier losing his fire.

Existential questions have long haunted both programs. Why hasn’t North Carolina, good or great in just about every other sport it sponsors, discovered the same formula for success in football? And why can’t South Carolina, which win or lose regularly fills up a 77,000-seat stadium, more often reward its support? Their rivalry, once fierce throughout the first two decades of the ACC’s existence, has waned since South Carolina -- again showing its will to secede -- left the ACC.

Yet it doesn’t take much to rekindle the embers. The reunion in Charlotte will do the trick.

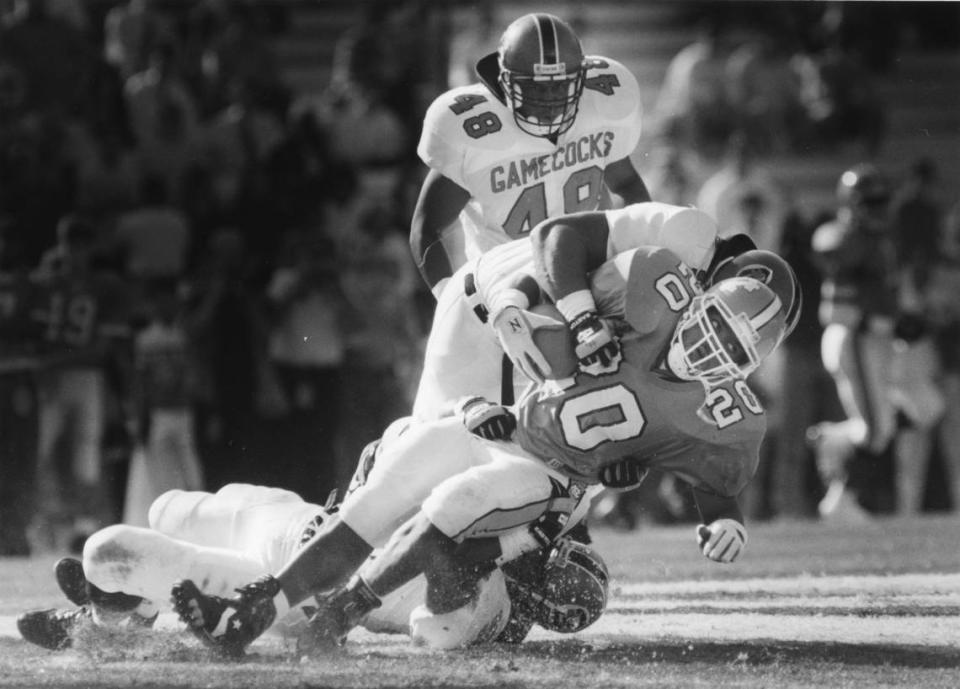

After a UNC victory in 1991 in Chapel Hill, the Tar Heels and Gamecocks went 16 years without playing each other. Saturday will be the sixth meeting in the past 16 years, with South Carolina victorious in four of the past five. As always, the rosters of both teams reflect the places that make Carolina Carolina, on either side of the state line.

The big cities are represented but also plenty of small ones, and towns built into the fabric of both states. Sumter and Dalzell and Mullins and Inman and Santee in South Carolina. Kernersville and Pilot Mountain and Shelby and Eden and Waxhaw in North Carolina. Woody Durham, the longtime radio voice of the Tar Heels, always referenced UNC players’ hometowns during his broadcasts. He knew it meant something especially to the people listening in out-of-the-way places, hearing their town called out through the crackle of a distant radio signal.

Sometimes both schools successfully woo defectors, with the Gamecocks recently luring more than their share. Four South Carolinians play football for North Carolina. Eight North Carolinians play for South Carolina. After last season South Carolina head coach Shane Beamer hired Travian Robertson, a North Carolina native who was a standout defensive end for the Gamecocks and returned to be their defensive line coach.

“We need more guys in that state to follow his lead and come across the border south,” Beamer said recently, countering UNC coach Mack Brown’s longtime mantra that North Carolina’s best high school players need to stay home.

The game Saturday comes almost 120 years after the first between the Carolinas. On the day of it, the entire front page of The State newspaper in Columbia detailed the murder trial of James Tillman, the South Carolina lieutenant governor accused of fatally shooting the co-founder of the newspaper. (And they say the press and politicians get along worse now.) Buried in the middle of page eight was this headline:

“A GREAT GAME THIS AFTERNOON,” above a subhead that read: “North Carolina and South Carolina Will Play for the Supremacy of the Two States.” Hyperbole, perhaps, but then again this was football in the South. The first game between the two was perhaps to be “the greatest football game ever seen in Columbia,” according to the story.

“The Carolina boys are determined to win the game, which will mean so much for them.”

Has all that much changed over the past 120 years? Well, yes. A lot of things.

But then, like now, a football game can settle old scores. It can help decide “the supremacy of the two states,” at least among those who view the Carolinas through a certain lens. Then, like now, the Carolina boys remain determined, even if it’s not entirely clear which Carolina they represent.

The Carolina that emerges victorious will inspire hope that it’s only the beginning of a rare kind of football season in Carolina’s cursed football history. A defeat, meanwhile, would deliver the kind of misery all too familiar for Carolina. One Carolina will walk away feeling superior to the other; the other feeling a tinge of envy. Same as it has been for the past 300 years.