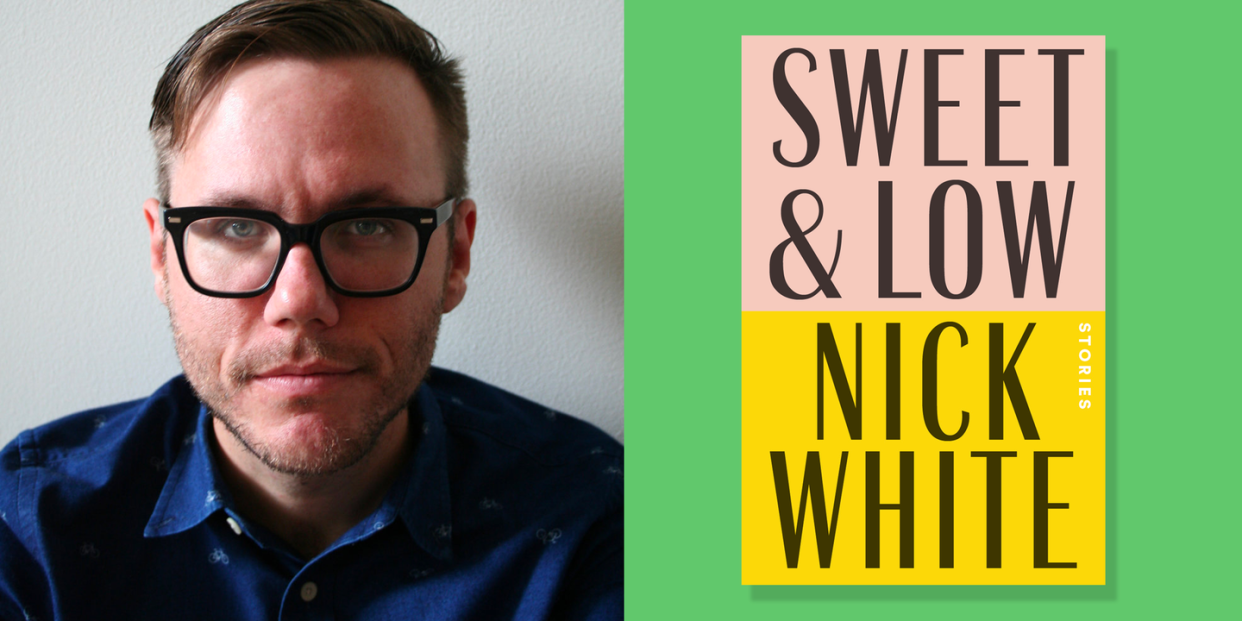

Why "Sweet & Low" Author Nick White Waited Until 30 to Come Out to His Parents

In OprahMag.com's series Coming Out, LGBTQ change-makers reflect on their journey toward self-acceptance. While it's beautiful to bravely share your identity with the world, choosing to do so is entirely up to you—period.

Mississippi-born author Nick White is particularly good at depicting what life is like for LGBTQ folks in the Deep South. His debut novel, How to Survive a Summer, takes place at Camp Levi, a gay conversion camp, while several short stories in his celebrated collection, Sweet and Low, focus on themes such as identity and sexuality. Here, White, an assistant professor of English at The Ohio State University, revisits two jarring phone calls that changed his life.

In 2015, after I signed my book deal and mailed it off to the publishers in New York, I figured it was probably time to come out to my parents. Like me, my novel was very queer, and I realized my folks back home in Mississippi would probably want to hear about it from me before they read it in the papers. Also: I was 30 years old and had been seeing the same man for three years. What I mean is the conversation was long overdue.

I had put it off because I knew they would find it difficult to have a gay son. They were conservative Southern Baptists who lived in the small rural community of Possumneck. I didn’t know how it would all go down, but had prepared myself for the worst: that once I told them, we would never speak again. I understood how strong the ties to their community and their faith were. I knew this could be goodbye. It would be hard, but I could survive it. In the six years since leaving Mississippi and embracing myself, I had amassed a group of friends who loved and accepted me for the fabulous person that I was. I would be okay.

I chose to call my mom from my office on the campus of the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, a windowless space I shared with two other queer comrades in the PhD program. In there, I felt cocooned, safe. Like I would be making this dispatch to Mississippi from a kind of impenetrable bomb shelter. No matter how horrible the fallout, I would be protected. Plus, my autographed picture of Bea Arthur, the patron saint of gay men in crisis, hung on the wall above my desk, smiling down at me with this bemused expression I found immensely comforting.

My mother answered on the second ring, already talking. I had been building up the nerve to call her all day, and now it was the evening. She was driving home from work on Highway 440, a curvy stretch of two-lane that cut through pastures and woods. Deer were liable to pop out in front of her headlights at any second, she told me.

“My god,” I said. “Do I need to let you go?”

She laughed, explaining how she had just figured out the Bluetooth system in her car. Now she could chat with both hands firmly on the wheel, eyes trained on the road. “And your voice is coming in strong, son,” she said. “It’s like you’re riding shotgun.”

So I forged ahead, leading off with the book deal. She was thrilled. Never one to be bashful about the bottom-line, she asked me how much they were paying me, and when I told her, she clicked her tongue. “They must really want it,” she said. And they did. But it’d upset her once she knew why. During a conference call with the publishers and my agent, a person from publicity had remarked how “current” and “timely” my “platform” was. Which seemed odd. All of my queer friends were already out to their parents. Even most of my queer students were. I felt old-fashioned for still being in the closet. Worse: I felt like a coward. Like I had no business telling queer stories when I was still too afraid to tell my own to my family.

“There’s something else I need to tell you,” I began. “And it’s hard.”

She said, “You can tell me anything—you know that.”

But did I? She hadn’t asked me if I was dating someone in a long time. I had interpreted her silence as proof that she knew, on some level, I was gay, but was just in denial about it. In my wildest fantasies, when I came out to her, she would say, “Duh,” having put two and two together a long time ago, and then proceed to pester me about grandchildren. That’s not what happened.

After I told her, my garrulous mother was rendered speechless. She drove, and I listened to the silence. This awful, inhumane silence. At last, she announced that she was pulling the car over. I said that sounded like a good idea. I gave her enough time to park before I asked if she was okay.

She said, “How long have you known this about yourself?”

I told her it was complicated. “Maybe always,” I said. “But I didn’t start accepting it until about six years ago.”

“Six years,” she repeated. “Jesus.” I honestly didn’t know if she was praying or cursing. “Are you seeing, um, anybody?”

When I gave her my partner’s name, she repeated it several times, as if she were trying out the sound of it in her mouth. “And what sort of person is he?” she asked, and I assured her that he was a good person. The best person. And successful, too. “He teaches at Harvard,” I added. Usually, I didn’t like to bring up where my partner worked. No matter how you phrased it, you always sounded like you were bragging. But now I was absolutely shameless. I even repeated lines from his CV: the names of the fellowships he had won, the title of his book, the number of his publications.

My mom was more interested in his surname. “Is he Jewish?”

“And Canadian,” I said.

“Is this a joke?” Her voice broke. “Are you making fun of me?”

Weeks later, my mom would claim not to remember much of what she had said in this moment. She did recall, however, how she felt, how she experienced this sensation of having driven into another world. “I left work thinking life was one way,” she said. “And by the time I got home, it had become another thing altogether.” A boyfriend, a book deal—everything, all at once. She needed the world to slow down, but it was moving far too fast for her.

She had parked her car beside a pasture. Several feet from her window, a cow was milling in the grass. She would later tell me how this creature looked familiar and kind, with its thick haunches and wide wet eyes. Never much of an animal person, she found herself resisting the urge to get out of the car and give this grazing heifer a hug. “Sometimes,” she said, “you just want something, anything, to hold on to.”

“You still there?” I asked.

My voice triggered another question. “Why are you telling me this now?” she wanted to know. But the answer occurred to her as soon as the question had escaped her mouth. “You didn’t write about this, did you?”

Now it was my turn to be silent, and then she said I needed to call my dad. He was a truck driver and was somewhere in Louisiana tonight, but he always kept his phone close by. I was emotionally spent, and suggested we keep this between us for now. “Maybe tomorrow,” I said.

“Oh no,” she said. “I am not going through this alone. I’ll call him myself.” Before she hung up, she said, “We will figure this out, okay? I love you.”

I was quietly weeping at my desk when the janitor came into the office. After he emptied the trash cans, he noticed my tear-stained face and offered me a piece of chewing gum. I said no thank you, and he went on his way. What I wanted was a drink, a bathroom, a kind word from a familiar face. I was supposed to call my boyfriend and tell him how everything went.

As if on cue, my phone buzzed: it was my dad. I let it ring, considering just sending the call on to voicemail. He and I were very different men. There had been, sometimes, a distance between us; it was hard for us to figure out how to speak each other’s language, I think. My dad chewed tobacco and was a genius when it came to repairing small engines. At church, he was the music leader, and when he sang, his voice came out twangy and pure. But ultimately, in many ways, he was a mystery to me.

When I accepted his call, his voice came barreling through so forcefully I had to hold the phone away from my face. He was speaking loudly because he had bad cell service, he explained, and wanted to make sure I heard him clearly. “Are you happy?” he kept saying. “I mean, are you really happy?” I told him I was, and he said that was all anybody could ever ask for. “Life’s too short for you to be miserable,” he said matter-of-factly. “And anyway you know my love ain’t worth much, but it is unconditional.”

I tried to tell him I felt the same way but was sobbing too hard to make sense. He interrupted me to say, “And your mama tells me you are dating a nice Jewish boy from Sweden.”

“Canada,” I said.

“Well, I have just one question, and then I’ll let it be.”

Suddenly, my mind filled with all the possible uncomfortable things my dad might want to know about my gay relationship.

“Do you still eat pork?” he asked.

“What?” I launched into this rant about how I was still the same person, that he shouldn’t make assumptions about people, that my boyfriend ate pork, but his laughter cut me off.

“That’s good,” he said. “Because I can love a gay son, easy, no problem. But I don’t think my heart could take any child of mine who no longer appreciated bacon.”

For more ways to live your best life plus all things Oprah, sign up for our newsletter!