Why it took Sister Souljah 22 years to write a followup to her groundbreaking novel

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1999, Sister Souljah published her first novel, "The Coldest Winter Ever," considered by some to be the mother of what's been called urban or street fiction and its first classic.

Its heroine, Winter Santiaga, the pampered daughter of a Brooklyn drug kingpin, uses her feminine wiles and hustler mentality to survive after her father's empire suddenly comes crashing down. "The Coldest Winter Ever" was one of the best-selling novels of 1999 and has since sold more than a million copies. Needless to say, the publisher wanted more.

"Quite naturally, the book company and everyone [else] expected me to write the sequel," said Souljah by phone from the United Arab Emirates, where she had gone to find "peace of mind" and to finish a draft of the book's long-awaited screen adaptation.

But because Winter Santiaga's story had ended with a mandatory 15-year prison sentence, Souljah felt she had to wait until Winter's time was served. "I didn't want to feed the hood a fantasy that going to prison is a joke or a cakewalk," she said. "Like 'Ta-da! Here she is,' and it's all good. There are real consequences to the things that happen in real life."

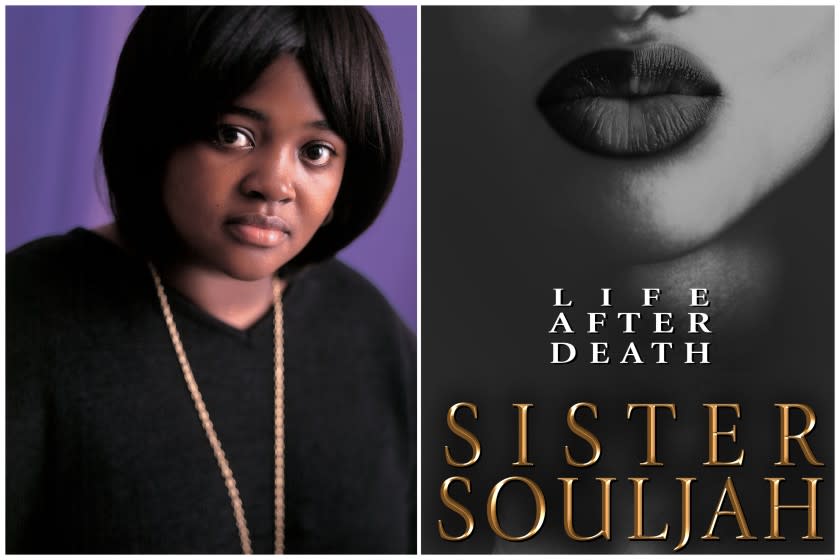

So instead she wrote spinoffs: three books about Midnight, the handsome and capable lieutenant of Winter's father, Ricky Santiaga, and one about Winter's younger sister Porsche, who ends up in juvenile detention. She even planned to write a Ricky story (and still hopes to). "But the character was always alive in my imagination," Souljah said. Finally, 22 years later, Winter is back in "Life After Death," out this week.

True to Souljah's insistence on consequences, the sequel begins with a hard shock: Winter is dead, stuck in a purgatory known as the Last Stop Before the Drop, and given one last chance to avoid eternal damnation. "People have said, 'It's so unexpected,'" said Souljah. "And I say, as an author, if I write what any reader expects me to write then I've failed because that means the readers could have written the book. I want to write something that you never would have imagined."

Though Winter's journey in "Life After Death" may take place largely in the metaphysical realm, there's still plenty of sex, danger and debauchery. "I didn't want to write a book where everything looks the same as how people expect or imagine," said Souljah. "Growing up Christian, there's the devil and he has horns and a tail ... It doesn't resonate with what you can see with your eyes in the real world."

Preparing to invent her own underworld, Souljah researched religious texts for seven months, "[mainly] nonfiction works that refer back to the major three books: The Torah, The New Testament and the Qu'ran."

She also read Dante's "Inferno," which she didn't like. "I thought it alienated the reader, the way that it was written," she said. "I never want to write books like that. I want you to read [my] books and be blown away because it was so close to your own soul and experience and you can take things from it and use it in your own real life."

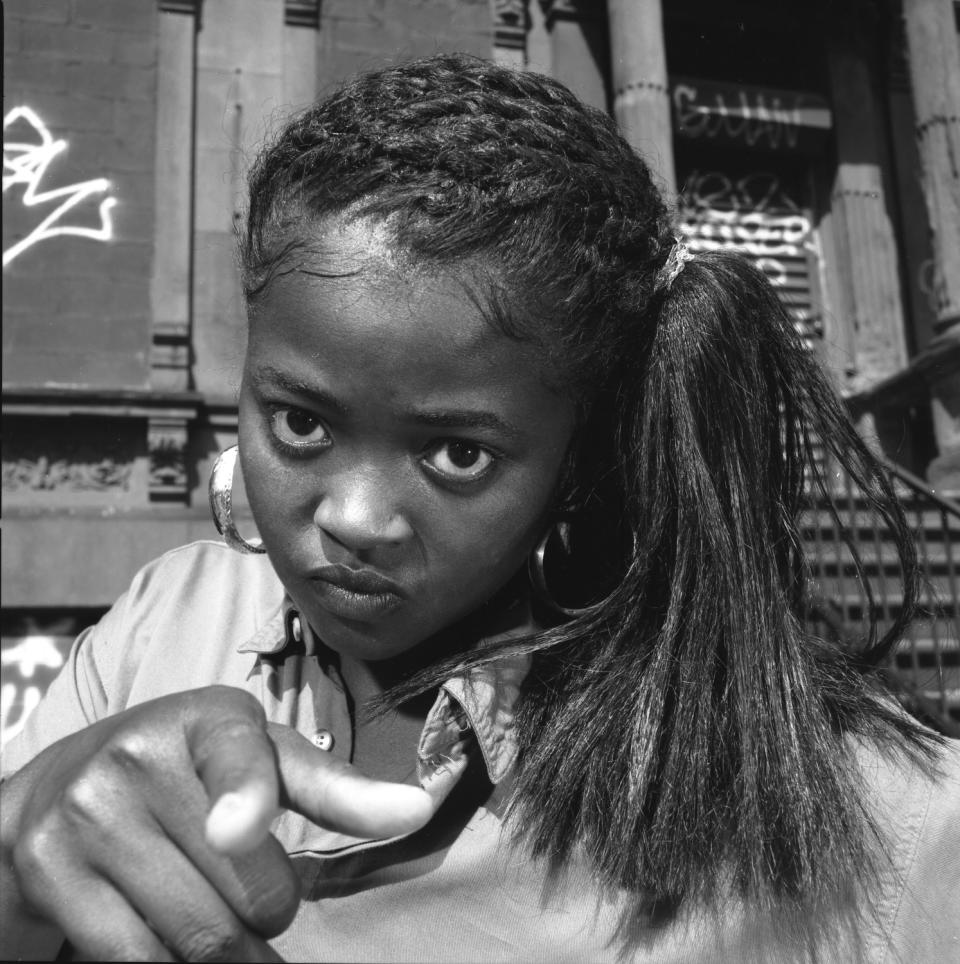

Souljah's outspokenness made her a flashpoint of national politics long before she wrote her bestselling novel. For a time, she was a member of the anti-racist rap group Public Enemy, and in the wake of the 1992 L.A. riots she said publicly, "If Black people kill Black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?" Then-Presidential candidate Bill Clinton denounced her. (She responded that her quote had been taken out of context.)

Ever since, any political denunciation of radical ideas (like Barack Obama's over Jeremiah Wright) has been glossed as "a Sister Souljah moment." Asked how she feels about the term today, she said, “A Sister Souljah moment is simply 'a moment of truth.’ And the truth should never ever be considered radical or un-American."

Souljah's books counter the caricature of her as an advocate of violence. Having grown up (as Lisa Williamson) in the South Bronx during the drug-ravaged '70s and '80s, she says she wrote "The Coldest Winter Ever" as a cautionary tale. "It was my desire to show our people that this lifestyle that we glorify is actually a death-style," she said. "And it doesn't end nicely, almost ever."

As a child, she lived in fear of the heroin epidemic. "It was explained to me and my brothers and sisters as a life-or-death situation," she said. "People carried around needles in their pockets. I was horrified about people drugging me or anyone in my family. I would say my prayers before bed and ask for protection."

Soon she began to notice the glamour of the drug-dealer lifestyle. "When you hit the teen years, I think that's when you notice the flash. So I wanted to write a story about drugs without writing something that preaches to people because I didn't think that preaching was something that people would accept, listen to or learn from," she said.

She'd thought about writing from the perspective of a dealer before trying something closer to her experience: "I do know about girls and women and love."

Though Souljah is often credited with igniting the urban/street genre, she considers the category inherently racist. "When a Black author writes, it's not literature," she said. "I mean, who are these 'street' people anyway? What are people who are not street authors writing about? The topics are the same. 'Romeo and Juliet' is a battle between families that are basically in gangs, so why don't they call Shakespeare street literature?"

She finds the idea of a lower class of writing insulting. "If you look at my characters and my storytelling, it spans from the inner city to the suburbs to several countries outside of America. You'll see Japan, Korea, China, the UAE and Oman mentioned. And before writing about these places, I normally travel there and stay long enough to get a sense of the people, the culture, the language. So why belittle all of that effort by then saying 'No, this is only urban literature. Only a certain set of people will buy it and understand it and that's why we put it in the back.'"

Rumors of a film adaptation of "The Coldest Winter Ever" have been circulating since the early aughts. In 2008, Jada Pinkett Smith told Vibe magazine she was set to executive produce the film. But nothing ever materialized. "'The Coldest Winter Ever' is a classic," said Smith by email. "Timeless. When [it's] ready to be made into a movie, it will be. Sometimes you have to wait for the right timing for certain creations."

Souljah considers it worth the wait. "My thing is, I want to have the movie but I want the business of it to be correct," she said. "I try to do business [in a way] that matches the art that I create. I don't want to do business in a way where somebody just processes me ... I read the contracts and I'm told that no one does that in Hollywood."

Today she's attached to a deal with a major studio; she delivered the script in July 2019 and expected it to go into pre-production that September. Then there was a contract delay. Then there was COVID-19. "So I'm not quite sure what will happen next," she said. "But I'm grateful that books stand the test of time and keep coming out no matter what. The pandemic is still a good time for [authors]."

Which means it's a good time for her. "Because you're basically just writing," she says. "There's nothing else to do."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.