Ireland’s Untamed Beauty Makes It a Beast to Ride

It nearly all went sideways when me met the full force of Hector. On our seventh day, with 1,800km under our belts, Brad and I had finally settled into a good groove. We were tapping the k’s over one by one, enjoying warm days, blue skies, and unexpected tailwinds along Ireland’s coastal traverse of the Wild Atlantic Way. We had trained rigorously through the wettest, grayest, and windiest of New England springs in preparation for the 2018 edition of the self-supported 2,500km TransAtlanticWay bikepacking race. We built up a surplus of what we cheerfully referred to as ‘Good Weather Karma.’ But in the steel-gray dawn on that seventh morning, and with a tentative lead in the team division, we rode blissfully unaware into the arms of Storm Hector. And Hector was furious.

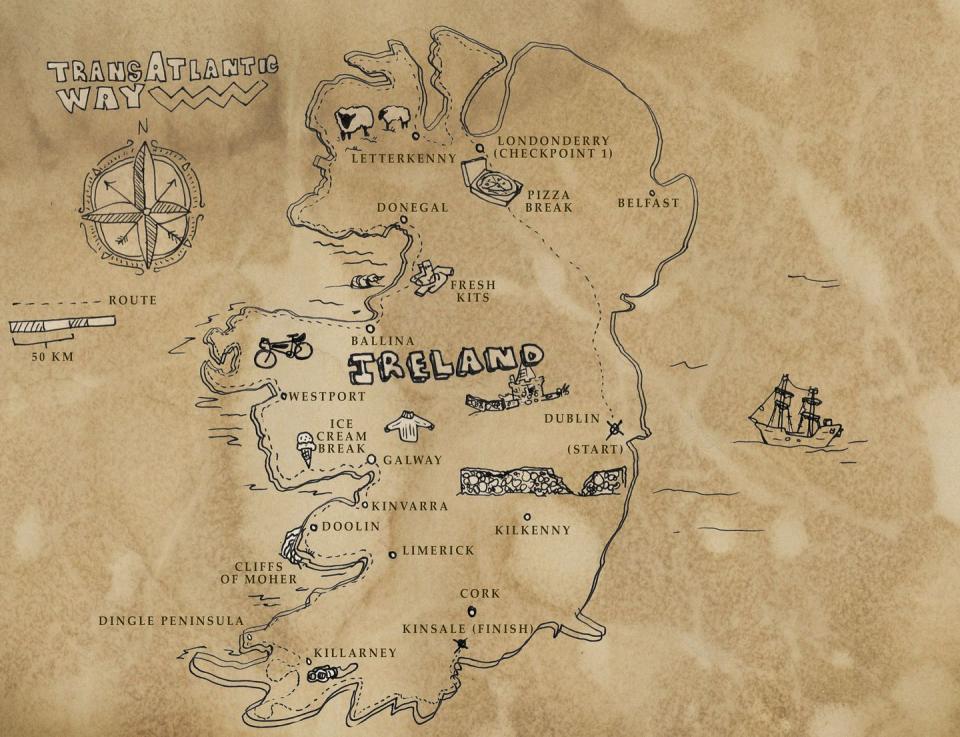

Months earlier, Brad and I each found out we hadn’t been selected in the Dirty Kanza lottery. We sat hunched over a laptop, trying to decide in lieu of the storied gravel roads of Emporia, Kansas, now what? Brad had previously raced the Trans Am Bike Race (4,200 miles across the U.S.), and I had a decade of ultracycling experience. So we settled on race director Adrian O’Sullivan’s 2,500km green-ribbon epic poem through Ireland. The self-supported race starts with an any-route-you-please section from Dublin to Derry, and then follows the storm-battered Atlantic coast through ancient villages, over mountain passes and otherworldly terrain to Kinsale in County Cork. The TAW checked every box: wild, remote, challenging, and definitely a little bit bananas. Bonus: There was a pairs division. We sent our registrations, fully committed. We were going to Ireland.

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that Brad Smith and I make an odd couple. Brad is a machinist at Seven Cycles in Watertown, Massachusetts, with, honestly, I have no idea how many tattoos (but one of them is a slice of pizza) and a carefree, it’ll-all-work-out attitude. (I’m also pretty sure that Brad doesn’t own any pants.)

I have a doctorate in immunology and work for a gene-editing company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with a single tattoo and an I-will-plan-this-thing-to-the-nth-degree-and-we-will-not-deviate-from-said-plan attitude. (I own several pairs of pants.)

But our love of bicycles, adventure, nature, finding (and pushing past) our limits, and a keen appreciation for the absurd supersede our differences. On those truly miserable days, when everyone else is indoors Zwifting, we’re out there, giggling in the face of headwinds, talking about pizza. When we ride together, it’s quite simple really: There is a lot of joy.

In the months leading up to the TAW, Brad and I planned and prepared meticulously. We had new Seven Cycles Evergreen XX gravel bike prototypes, with SRAM, Zipp, and Donnelly 650b tubeless tires. We had clothes and bags from Rapha; helmets, shoes, and lights from Bontrager. There would be no excuses equipment-wise. We plotted out daily goals (a little more than 300km per day) booking B&Bs for every night, thinking that even if we couldn’t get any shut-eye, we would welcome a nice shower and a meal after a long day in the saddle.

JUNE. DUBLIN. BRAD AND I WRESTLED OUR bike bags through the crowds at the hallowed gates of Trinity College. Instantly in awe of the history surrounding us, we uttered the first of what would probably amount to a million wows. A muddle of bike bags, boxes, and partially built bicycles littered Parliament Square, their owners focused intently on the task, hiding any prerace jitters. In less than 48 hours, we would toe the line with 130 solo racers and seven teams. We were as ready as we could be. We just wanted to start pedaling.

Two things about meticulously planning for a two-person bikepacking race in Ireland: First, don’t. It turns out that your teammate’s cramping legs 60km in on the first day don’t care about your logistical acumen. A hiccup like that makes a slipshod mess of the most careful strategies. And second, you don’t need to. There are thousands of hostels and B&Bs dotting Ireland’s west coast, and smartphones are a wonderful thing. A later-than-planned start on Day 1 (teams were the last to stage) had us arriving in Malin Head hours later than we expected, which meant that instead of sneaking out the door before anyone was stirring in the B&B, we woke to the smell of coffee and muffins and eggs and toast. So yeah, Day 2 got off to a late start, too.

Any concerns we had about our faltering strategy melted away that morning. The all-business Day 1 opening salvo from Dublin to Derry meant that our first views of the Wild Atlantic Way were reserved for the next morning. The ocean shimmering to our right, we drifted through a paved couloir, bucolic farms on one side, abrupt cliffs on the other. We were drunk on rolling emerald hills. Our giddiness reached a pinnacle later that day. We had heard about the gravel descent of Glenveagh National Park, whispers and anxious chatter about the 7km rocky, narrow goat path, and had been licking our chops in anticipation. A small group of riders gathered around a wood and metal gate that opened to the valley below. Maybe it was because of our tires (big ol’ Donnelly Strada USH 650B x 42s) or our grin-plastered faces, or both, but the group encouraged us through the gate first. We hooted and hollered our way down, as the waters of Lough Beagh glittered blue below. Our faces hurt from smiling.

IT TOOK A FEW DAYS FOR US TO SETTLE INTO the rhythm of life on the road. On Day 4, though, everything started to click. With our early missteps, we hadn’t dared look at the tracking page to see how our competitors were faring. But that morning, after silently pedaling past a duo snoozing in a farm field, we suspected (and then confirmed) that we had just passed the current leaders of the team division: George Cordal and Victoria Mayes from the U.K. The realization that we had a chance at the team victory was just the shot of adrenaline we needed—and kicked off a cat-and-mouse game that would carry us into Hector’s wild embrace.

Over the next few days, George and Vic would wait until we had stopped for the night and press on, piling on k’s while we stacked z’s. At some point the next day, we would pass them. With the halfway checkpoint less than 100km away, we slipped out of our B&B in the wee hours of our fifth day. During the approach to Coonemara Hostel, we spied two red taillights in the distance. George and Vic. They had passed us again. Brad and I, embracing our “fast on the bike, slow off the bike” reputation, cruised past George and Vic, exchanging pleasant morning greetings. Later we joked about who was going to sneak out on the road while the other went to the bathroom.

With a capable duo hot on our heels, race tactics were back on the table. The race to the ferry in Shannon would offer our first big chance to catapult ahead of the chasing team. If we got pedaling shortly after midnight on Day 6, we could make the first ferry and cross the Shannon Estuary with an hour cushion before the boat would return to make the same trip again. In a 2,400km race, an hour is nothing, but being first to the ferry felt like a psychological boost. If we were in a position for PSYOPs, we were in a position to win.

The midnight departure meant that we passed the Cliffs of Moher in darkness, oblivious to their dizzying heights and stunning beauty. Instead, we climbed to our highest peak, the 1,500-foot Conor Pass, and had a parade lap around the craggy cliffs and sandy beaches of the Dingle Peninsula, all in broad daylight and blue skies. We stopped for photos, made small detours, and met the locals. We were peppered with “Hullo, lads!” from weathered old Irishmen who seemed caricatures of weathered old Irishmen. Half joking, we found ourselves thinking that we would be a lot faster if Ireland were uglier. It was a sublime day. Rare for the Dingle Peninsula. And an ominous calm before the storm.

IN THE MIDDLE OF AN EVENT LIKE THE TAW, everyday things like the news or the weather or reality take a back seat to riding, sleeping, and eating. So when we rolled out of Milltown with an ambitious 400km on tap, we were wholly unaware of what was in store. At first light, as we plodded up the Gap of Dunloe, the first drops of rain began to fall. The wind picked up as we descended the Gap. Rain lashed and temperatures dropped. Circling the Ring of Kerry, we ran headlong into Storm Hector, which brought gusts as high as 125km per hour. On the climb up Ballaghbeama Gap in Kerry, wind-driven sheets of rain made forward progress near impossible. Bookended by Moll’s Gap, we survived the Ring of Kerry—barely. We descended into Kenmare, soaked and shivering. Stumbling into a large grocery store, we bumped into another racer, who stated cheerfully in his Scottish brogue, “I’ve been drier gone swimming.

How to Survive a Multiday Bikebacking Trip

Pack light. We carried the minimum: a kit, extra base layer, arm and leg warmers, long-fingered gloves, two pairs of socks, raincoat, cap, insulated vest, hanging-out shorts, and a fleece that doubled as an emergency on-bike layer. We brought basic repair supplies, tools, quicklinks, tubes, spare cable and housing, one spare cleat, plus enough tubes for two flats apiece.

Dial your setup.Never let your bike be the reason you don’t finish. Before you leave, replace worn parts and equip your bike for the terrain and conditions.

Ship ahead. We pre-shipped supplies to our B&Bs every few days so we had fresh kits, food, and drink mix. What we didn’t use, we shipped to the finish. Pro tip: Clear this with the race promoter. Events like the Trans Continental Race frown upon mail drops, while others like the TransAm consider it part of the game.

With nothing left to do but roll onward, I remembered Andy Hampsten’s famous ride up the Gavia at the 1988 Giro d’Italia. At the top, in the middle of a snowstorm, he stuffed newspaper in his jersey for added warmth. Inspired, I found some free papers and together Brad and I filled each other’s jerseys. We added some rubber dish gloves at the checkout, and were ready for battle. Over the next four hours, Brad and I covered a stupendously slow and increasingly dangerous 56km, crawling westward along the Ring of Beara toward Dursey Island. A few miles east of Allihies, we finally met Hector’s full fury. Climbing a short pass with grades over 20 percent, I was blown across the road and off the bike. The edges of the road crumbled away to a gray void, the ground indistinct from the sky. I tried to get back on my bike but it kept sliding from beneath me, floating at a 20-degree angle from the pavement. I tentatively walked forward, hunched over the bar, hoping to keep the bike on the ground. Once I reached the summit, I found partial shelter from the wind, mounted, and began a cautious descent, all the while searching for Brad’s taillight in the distance.

We met up again a few minutes later after the corkscrew descent on the outskirts of Kilmackillogue Harbour, seeking shelter from the wind behind a small farmhouse. It was the first time we weren’t shouting to communicate since the grocery store hours earlier. Our destination, Castletownbere, some 65km away, seemed beyond unreachable, it seemed reckless. The hostel in Allihies would have to do. It had taken us a harrowing 18 hours to cover just over 280km, but we were done for the day.

Predicted winds for the next morning hovered around 60kph until 8:00 a.m., and a quick check on George and Vic put them at least four hours behind us. We slept like rocks and woke to a dazzling sun. We had the lead, a good night’s sleep, and the finish line a tantalizing 330km away. By the time we reached Mizen Head 10 hours later, we had opened the gap to our chasers to 100km. We tacked east, winds to our back, and raced to the finish line.

Seven days, 15 hours, and 43 minutes after leaving Dublin, Brad and I rode into Kinsale, exhausted, happy, but more than anything, grateful. A bleary-eyed Adrian, near delirium from a sleepless seven days, cracked open a lukewarm can of Guinness and handed it my way. Wilder than expected, more stunning than imagined, the experience had pushed us to the edge of failure, our best laid plans a twisted wreckage. But we survived Hector—and the Wild Atlantic Way.

You Might Also Like