Why Trump's 'guilty mind' could make or break his prosecution

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

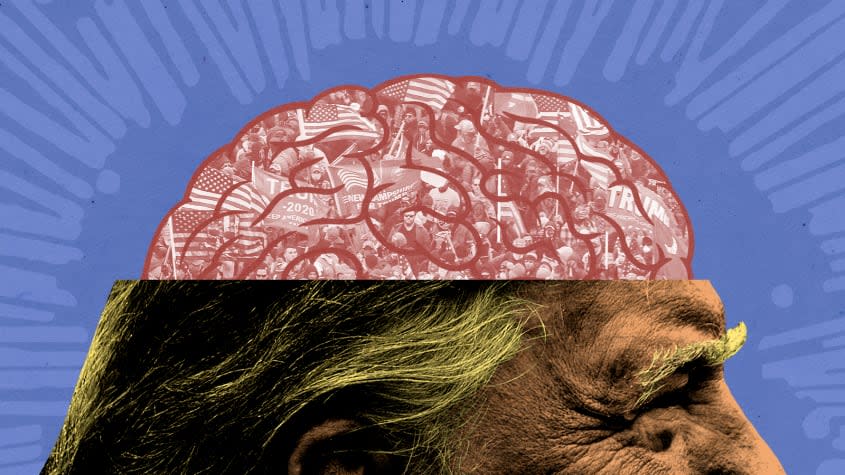

As the Jan. 6 committee continues to build its case against former President Donald Trump, one of the key issues for a possible prosecution is whether Trump and his legal advisor John Eastman actually knew he had lost the election — or if he really believed, wrongly, that he had won. The legal Latin for this is mens rea, or "guilty mind"

"Most or all the crimes that Eastman and other Trump advisors could be charged with would require proving a guilty state of mind," says Stanford Law School Professor David Sklansky. "This might require showing, beyond a reasonable doubt, that they knew that Biden's electoral victory was legitimate and not the result of voter fraud — or at least that they knew they were obstructing a legitimate government proceeding." And it can be difficult to make that kind of case against Trump, "who may have convinced himself of whatever it was convenient for him to believe." Can the Jan. 6 committee prove Trump had a guilty mind? And should it matter?

Bill Barr may have given Trump his "get out of jail free" card

During his testimony before the committee, Trump's former attorney general described him as "detached from reality" regarding his election loss. "Ironically, that seemingly damning assessment of Trump's state of mind might be his best defense against a possible criminal prosecution," Renato Mariotti writes for Politico. While Trump "seemed uninterested in facts" of his loss and "clung to implausible conspiracy theories," there's still a big challenge for a potential prosecution: "At the core of any fraud prosecution is proving the defendant's dishonesty and intent to defraud beyond a reasonable doubt." And that's going to be difficult to prove. In private, "Trump passionately pushed his fraud claims on anyone who would listen, and he is still pushing the claims now." That means the Department of Justice is going to be extremely cautious about charging the former president. "They charge defendants when they know they have the goods, and based on what we've seen so far, they don't have an airtight case against Trump."

Not every crime requires proof of mens rea

"For a number of the possible crimes the committee has identified, it doesn't matter what Trump believed about the election," Ryan Goodman, Norman Eisen and Barbara McQuade write in The Washington Post. He had no right "to engage in other extralegal means to try to hold onto power," including pressing Georgia officials to find extra votes, leaning on Vice President Mike Pence to violate the Electoral Count Act to send the election back to the states, or asking Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers to substitute Trump's electors for Biden's. You don't have to prove that Trump really, truly believed he'd won the election when the evidence shows that "Trump and a cadre of his closest associates conspired to engage in electoral vigilantism," the trio write. "Whether one truly believed their preferred candidate won the election or that the official verdict was flawed is simply no defense." And that means prosecutors have a clear pathway to charging Trump. "If they focus on Trump's efforts to engage in vigilante justice, the intent element of these crimes is easily satisfied."

If Trump didn't want to know the truth, that's a strike against him

If they can't prove that Trump knew he lost the election, prosecutors "could rely on a well-established legal doctrine well-suited for this situation: 'willful blindness' or 'conscious avoidance,'" Daniel Richman writes for Lawfare. This isn't just a "should have known" situation — prosecutors would have to make the case that "the defendant subjectively believed that there was a high probability that the relevant fact was true and that the defendant took deliberate actions to avoid learning that fact." That's still pretty difficult to prove, however: "Delusional pigheadedness is indeed a defense." Criminal trials "regularly require trips through a defendant's head," and that means the best-case scenario is still challenging for would-be prosecutors — particularly with a defendant as famously disdainful of the truth as Trump. "No one should underestimate the difficulty of a trip into the head of someone who has had a troubled relationship with expertise, precedent, and reality."

Even if he didn't have a guilty mind, he's still guilty

"Here's a thought experiment. Imagine applying mens rea to the bloodiest tyrants of modern history," Timothy Noah writes for The New Republic. Hitler, Stalin and Mao were all apparently true believers in their murderous causes, but it wouldn't be hard for a smart lawyer to make the case they "suffered from severe mental illness that prevented them from feeling guilt about their butchery." That shouldn't matter. Trump isn't a mass-murder like those men, but that doesn't change a singular truth: Believing one's own BS doesn't end one's culpability for crimes. His self-delusion is no reason not to put him on trial. "Trump is not impaired," writes Noah. "He's just a rich a--hole who believes what he wants because he can."

You may also like

Clarence Thomas: Supreme Court should 'reconsider' rulings on contraceptives and same-sex marriage

Did Texas Republicans endorse secession at their party convention?