Why the U-2 Is Such a Badass Plane

On October 27, 1962, the world focused on the tiny island nation of Cuba as two global superpowers—the U.S. and the Soviet Union—appeared on a collision course toward nuclear war. But as the drama unfolded in the Caribbean, another international incident was playing out in secret over eastern Siberia.

Captain Charles W. Maultsby had been tasked with a flight to the North Pole as part of a broader mission tracking Soviet nuclear tests. Long before the advent of GPS and too far north for his compass to be of much use, Maultsby used only a sextant and the stars to navigate, like a sailor from a bygone era. As he was making his way home, the Aurora Borealis made it impossible for him to distinguish between the stars and he’d managed to head directly into Soviet airspace.

Maultsby’s communications were muddled by the distance as Soviet radio operators tried to fool him into heading deeper into enemy territory. Mig-19s had been scrambled from multiple Soviet air bases with orders to shoot down the American spy plane.

Maultsby was in trouble, but he was a seasoned veteran and capable pilot. Maultsby kept his head and made course corrections based on where he was receiving Soviet radio broadcasts, hoping to aim the nose of his aircraft toward safety.

All the while, Soviet Migs jockeyed for position 10,000 feet below him. Their service ceiling was 60,000 feet, stopping them from reaching the slow-moving unarmed reconnaissance plane. It wouldn’t take much to shoot the U-2 down—if Maultsby turned too hard the wings would just fall off. In fact, the only thing keeping the American pilot safe was the cushion of air between his aircraft and the fighters below.

But with his fuel stores dwindling, and he knew he couldn’t keep it up forever. Maultsby hoped he was close to friendly territory and made the decision to kill his engines and allow the massive U-2 wingspan to glide him as far as they could. To his surprise, he maintained an altitude of 70,000 feet for about ten minutes before he started his descent.

He crossed 60,000 feet and wasn’t fired upon, and by the time he reached 25,000 feet, F-102s were on his wingtip, welcoming him home.

While there’s no denying Maultsby’s aviator grit helped return him safely back to American airspace, his high-flying chariot—the U-2—performed precisely how its engineers envisioned nearly a decade prior.

A New Kind of Threat

In 1949, the Soviet Union conducted their first atomic bomb test, and as early as 1950, they began aggressively intercepting aircraft that approached their borders. After a short time as the world’s only nuclear power, the U.S. found itself not only losing their monopoly but also the lead. The pentagon had glaring questions about Soviet bomber forces, their progress on developing ICBMs, and how many nuclear weapons the Soviets were stockpiling, with no clear path to finding answers.

America’s first reconnaissance satellites were still a decade away and it would be another twenty before they could offer the resolution officials needed to track the Soviet’s nuclear progress. So the U.S. needed an aircraft that could fly into Soviet airspace without being intercepted. Attempts at modifying existing surveillance platforms like the Martin B-57 to the task were quickly scrapped and it became apparent that the U.S. Air Force would need to build a completely new aircraft.

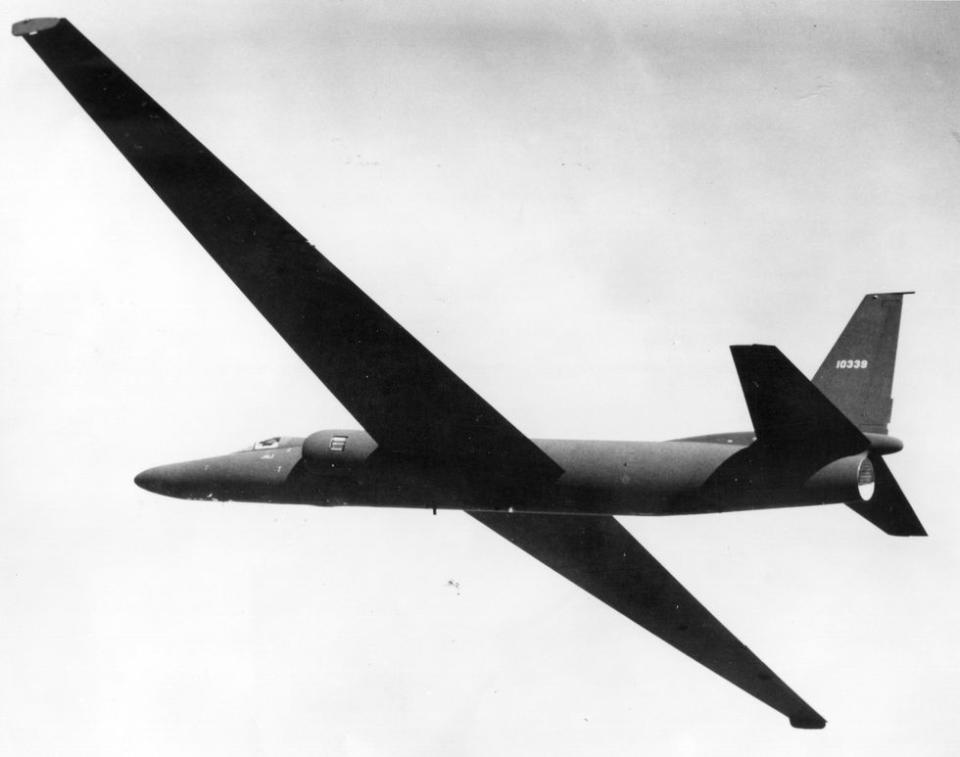

So in 1953, the Air Force started looking for proposals for a plane that could reach an altitude of 70,000 feet and fly for approximately 3,000 miles without the need to refuel. At the time, the best intercept fighter in the Soviet arsenal, the Mig-17, could only reach altitudes of around 54,000 feet and even most radar systems of the era couldn’t track targets above 65,000 feet. In fact, the U.S. had only put its first jet fighter, the Lockheed P-80, into service five years prior.

The aircraft also needed to house cameras that could take pictures with a resolution of just 2.5 feet from that altitude. No cameras at the time could do the job, so Lockheed contracted James Baker from Harvard and Richard Scott Perkin of the Perkin-Elmer Company to custom build a series of cameras that could achieve the resolution required without breaking the new aircraft’s payload limit of just 450 pounds.

Kelly Johnson, the chief engineer for Lockheed’s Skunkworks, had already designed the P-38 and F-104 for the U.S. military and would eventually go on to design the SR-71 Blackbird—but his unusual proposal for a modified XF-104 fuselage with a single engine, glider-like wings, and no retractable landing gear was just a bit too odd for the U.S. Air Force. They passed on the design.

Flying High

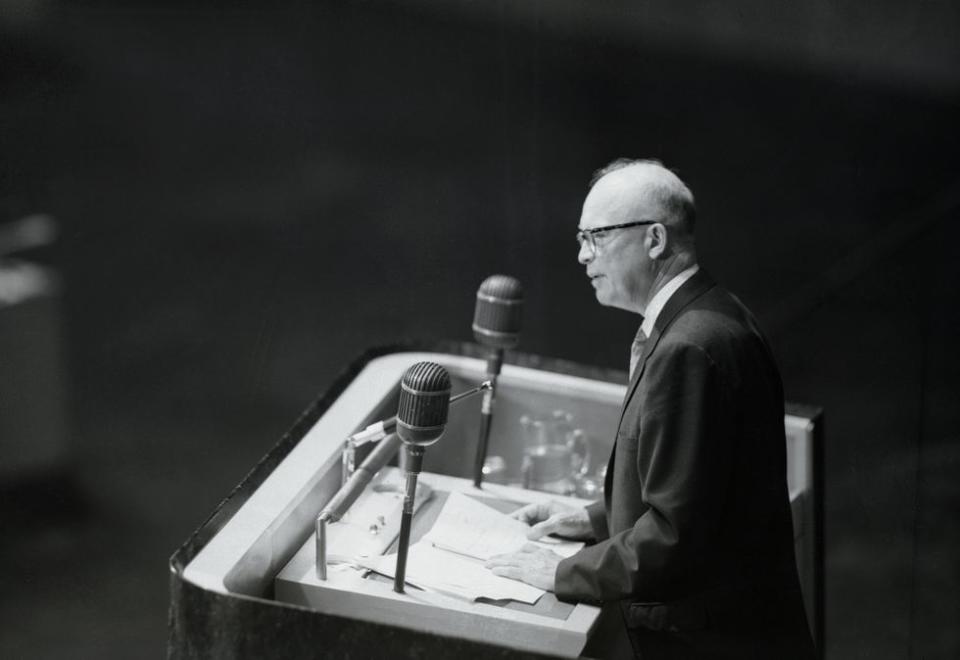

But President Eisenhower had other plans. Eager to get eyes on the Soviet nuclear program, Eisenhower authorized the CIA to move forward with its own reconnaissance program.

So Lockheed set about designing and building the new U-2 in just 8 months. With no computers to rely on, Johnson and his team worked in secret and by hand, often fabricating parts during off hours and on Sundays at their Lockheed factory to preserve the program’s secrecy, even from other employees.

And the challenges Lockheed faced were massive. At 70,000 feet, the atmosphere was barely thick enough to keep an aircraft aloft and a loss of cabin pressure would result in the pilot’s blood boiling.

“The whole reason we wear a full pressure suit is to protect us from decompression sickness and the low pressure environment at high altitude if we were to experience a rapid decompression,” U-2 Pilot Major “Torch” Miller of the 99th Reconnaissance Squadron tells Popular Mechanics.

“Without the pressure suit, a rapid decompression in the cockpit would cause the nitrogen in your blood and tissues to come out of solution and go into your bloodstream, your joints, and possibly make its way to your brain, which would most likely be incapacitating and potentially kill you.”

But despite the danger, the CIA considered that extreme altitude essential as it was considered high enough to avoid engagement from Soviet fighters or surface-to-air missiles, and may even be high enough to avoid radar detection altogether.

Problems at Area 51

The first U-2 flight took place on August 1, 1955 on a remote dry lake bed in Nevada that the CIA and Skunkworks team took to calling "Watertown." It was surrounded by the Atomic Energy Commission’s (AECs) nuclear testing ranges and active air ordnance testing sites, which combined with its remote location made for the perfect spot to keep their new prototype aircraft away from prying eyes.

That dry lake bed, airstrip, and hangar would go on to serve as a test site for many other classified aircraft and eventually earn fame under a different name: Area 51.

But those early test flights were far from flawless as new problems began surfacing. Seals began to leak at the high altitude and the brakes on the unusual landing gear couldn’t slow the aircraft down. Even the jet fuel caused problems due to a lack of atmospheric pressure, causing the engines to flame out due to fuel issues at altitude. And its massive wings didn't help things because the aircraft had a tendency to float above the airstrip as pilots tried to land.

While both problems were addressed, neither were completely eliminated.

“Landing her was a challenge each time as it came at the end of a very long mission,” former U-2 pilot Sam Crouse tells Popular Mechanics. “It was a true balancing act, stalling her out at a foot above the runway and making sure the tail was down as the rudder lost effectiveness and the tailwheel took over for steering.”

Worse still, because of the light construction of the aircraft, there was a risk of breaking apart if pilots pushed the plane too hard. As testing continued, pilots found what they called the aircraft’s “coffin corner,” which was a range of just about 6 knots that the aircraft could operate properly in at 70,000 feet. Too slow, and the engines could flame out. Too fast, and the aircraft might break apart entirely.

Despite issues and crashes throughout the classified testing period, the need to know the state of the Soviet Union’s nuclear plans was great enough to push the U-2 in operational flights just one year after it first took to the sky.

Teaching an Old Plane New Tricks

For four years, the U-2 operated high above the Soviet Union under the CIA’s purview. After a few years, it had become clear that the Soviets could spot the U-2 on radar and even scramble fighters to intercept, but its immense altitude managed to keep it insulated from any actual engagements. That is, until May 1, 1960.

U-2 Pilot Frank Powers had taken off from an airstrip in Pakistan with a flight path to Norway that would take him over 2,900 miles of Soviet airspace. Midway through his flight, Power’s U-2 was hit by a Soviet anti-air missile. Powers managed to eject, surviving the 65,000 foot fall only to be captured by the KGB.

Operating under the assumption that no one could survive an ejection at such high altitude, NASA announced that one of their research aircraft had gone missing somewhere over Turkey, potentially drifting off course into Soviet territory. They quickly painted a U-2 with NASA markings and gave it a fake serial number to create images for the press.

The Soviets allowed American officials to solidify their cover story for days before revealing that they knew it was a spy mission, and that they had the pilot in custody. The incident set back American and Soviet relations and Powers was ultimately traded, along with another American, for captured Soviet spy, Rudolf Abel.

This crash marked the end of the CIA’s U-2 flights over the Soviet Union, but it was far from the end for the high-flying U-2 itself.

“Aside from the SR-71, there’s probably not another aircraft with more unique history on its resume than the U-2,” Miller says. “What we did with the aircraft during the Cold War was pretty brash and I think some of that mindset is still in the DNA of how we operate today.”

From there, the Air Force took control of the U-2 program, where it remained for the better part of six decades. The platform has undergone repeated upgrades over that time, including adding even longer wings that stretched the U-2’s already impressive wingspan from 80 feet to a massive 103 feet. A new turbofan engine raised the platform’s operational ceiling to 74,000 feet while reducing flameouts and bringing the U-2’s top speed up over 500 miles per hour.

Other modifications that enabled in-flight refueling also increased its range from 3,000 miles to more than 7,000.

State of the art (and classified) instrumentation and sensor pods now allow the U-2 to spy on combat zones with greater accuracy and efficiency than ever before, and the U-2 peers into places where satellite observation isn’t able to meet mission requirements.

“In about eight hours, we can take off and we can map the entire state of California," Maj. Travis "Lefty" Patterson said of the U-2. "The fidelity is such that if somebody is holding a newspaper out...you can probably read the headlines."

Attempts were even made to modify the U-2 so it could operate from aircraft carriers, so the U.S. could do away with its reliance on foreign airstrips. But as far as the public knows, no U-2 surveillance flights ever took off from American carriers.

One Unusual Bird

Despite all the upgrades and changes, the U-2 remains as unusual today as it was at its inception. It’s strange, seemingly-lopsided landing gear housed within the fuselage is bolstered only by “pogos” at the end of each wingtip. Visibility is so limited inside the cockpit that pilots rely on powerful chase cars driving just behind the landing aircraft to give them much needed course-corrections as they descend. More than 60 years later, flying the U-2 is a unique experience, even among military aviators.

“It’s challenging flying patterns at low altitude because it takes a lot of concentration, and because the jet only has mechanical flight controls, it takes a lot of physical input to make the jet do what you want it to do,” Miller says. “Flying a long duration reconnaissance mission takes some mental and physical endurance. Being sealed up in a full pressure suit and strapped into an ejection seat for 11 hours is definitely not for everyone.”

In recent years, U-2 pilots have flown missions over Iraq and Afghanistan that can last for up to 12 hours, but the detailed intelligence they have provided on ISIS and Taliban positions throughout the regions have proven invaluable.

Unlike some other legacy aircraft in use by the Air Force, the U-2s in service today aren’t the same platforms that first took to the sky in the 1960s. There were a total of 104 U-2s built between the program’s inception and 1989, with a newer variant, the U-2R introduced as recently as 1981. This new version of the aircraft boasted a number of improvements, including a Side-Looking Airborne Radar for scanning the ground.

The Air Force planned to retire the U-2 in favor of the RQ-4 Global Hawk drone in 2014, but the U-2 still packs a reconnaissance punch that the drone couldn't replicate. The U-2 can mount heavier and higher quality sensors and costs less to operate.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Air Force’s fleets of U-2 spy planes were all converted into the new U-2S. All of the 31 remaining U-2s in service are technically hold the name "U-2S."

“We now fly a newer airframe that is larger and more robust with a new engine and modern avionics and sensors. It’s borne from the original 1955 design, but it’s a totally different beast,” Miller says. “I hope those kinds of advances and improvements continue to happen because this platform will be able to do amazing things far into the future as long as we continue to invest in it."

You Might Also Like