Why I Walked on the Moon

This story originally appeared in the July 1994 issue of Popular Mechanics, as part of our Apollo 11 25th anniversary package. Now we’re dusting it off for the big 5-0.

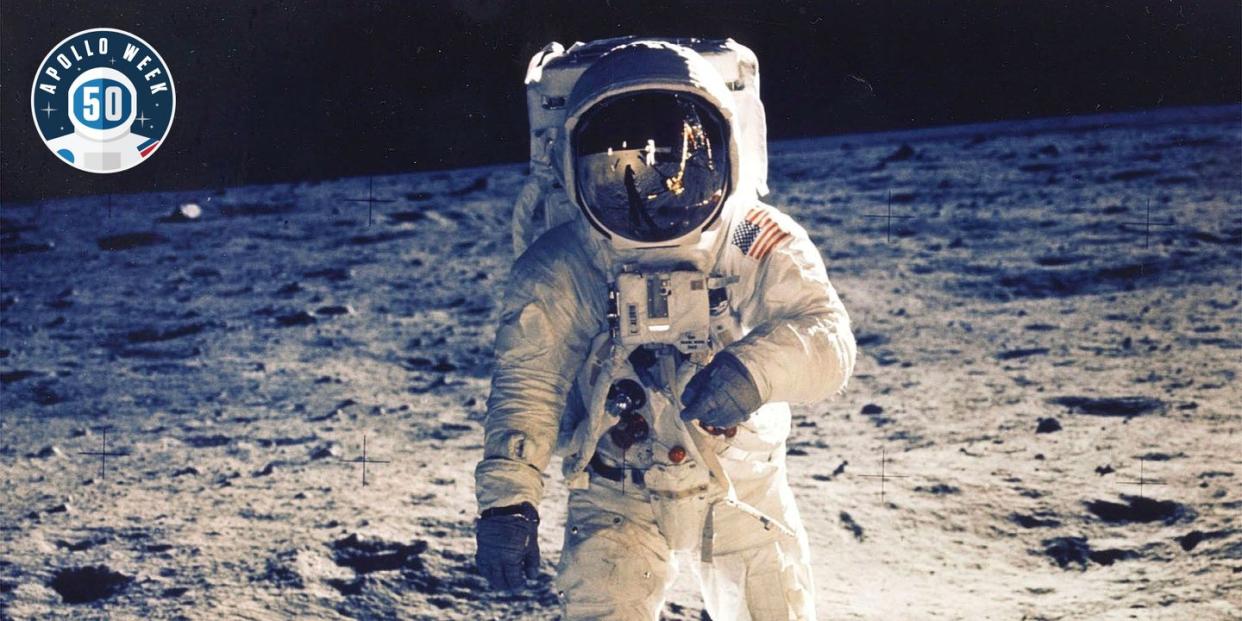

I don’t recall the precise words I uttered to Neil Armstrong when we slapped each others’ shoulders on the Moon—“We made it,” or “Good show,” or something to that effect. But today, a quarter-century later, certain memories remain as crisp as the shadows that creased that airless, desolate landscape. The perfect little waves of Moon dust that rolled away from my boots as I walked.

Later; back in the lunar module, its pungent smell—like gunpowder: The pleasure of adapting one’s movements to one-sixth of Earth’s gravity. The horizon that fell away within a mile or two. The clean blackness of the sky. Above all, the quiet.

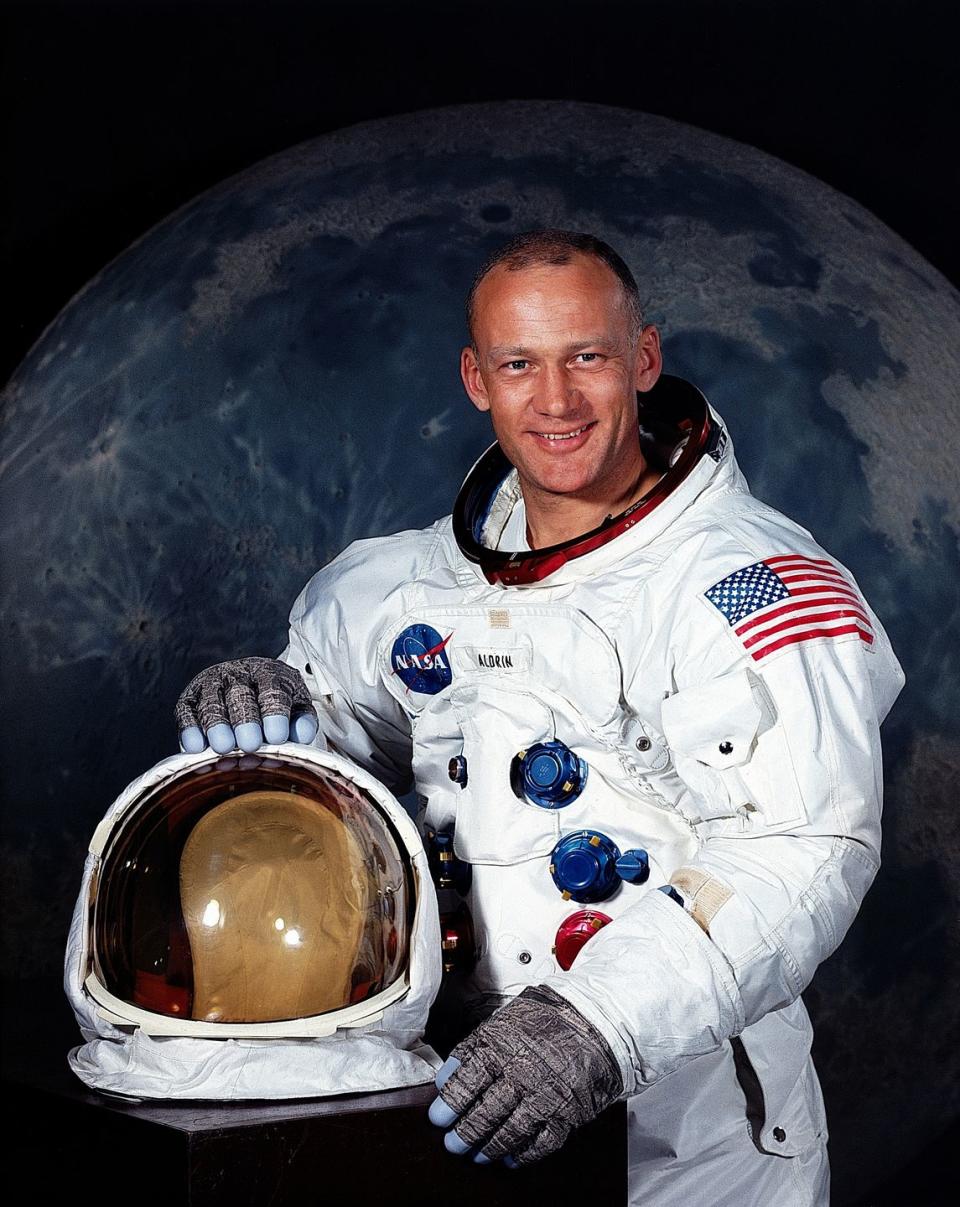

I hope Americans can experience that tranquility again. The national motivation that put us on the Moon remains unparalleled in the history of spaceflight. My own motivation, to see a continuous human presence in space, burns as brightly as it did in 1961, when I passed up test-pilot school to get my doctorate in astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Ironically, that decision nearly cost me a trip to the Moon because back then, when I first applied to the astronaut program, NASA held doggedly to the test-pilot requirement. But I felt I could contribute some original ideas on manned orbital rendezvous, and I pressed on with my studies.

My goal was already clear in my mind. I wanted to combine my background as a fighter pilot—an occupation of short-term reaction—with my desire to bring some imagination to the bigger, long-term picture. Sure enough, that desire is what ultimately brought me into the space program in October 1963. That—along with luck and timing and the labor of a hundred thousand colleagues—is what brought us to the Moon.

In a sense, the desire to contribute to the future is also what got me out of the space program. As the Apollo years slip into history, we tend to reminisce fondly about the good old days when things were simple and goals were well defined. Well, even back then it wasn’t simple (we’ll find that out if we try to do it again), but our objective was unambiguous, driven by the Soviet Union’s early prowess in space technology.

When you do something under a tight schedule, however, you don’t necessarily invest in it for long-term sustainability. That was the case with Apollo. Then, after the Moon landings, we wanted a destination—a space station—and a means of getting there—a space shuttle.

But nobody came to grips with an unfortunate reality, that the national motivation to invest in space for the long haul had dried up.

Take the shuttle, for example. In 1970, just before I left NASA, the space agency advocated a 2-stage, fully reusable spacecraft—a booster and an orbiter. Representing the Astronaut Office, I helped evaluate some of the early shuttle proposals along those lines. To my dismay, the NASA center that designed the booster wanted to put a manned cockpit in it, to help ensure its safe return to Earth.

To me, it just didn’t make sense, and I wish I had argued more aggressively against the idea. Putting people in the booster added such a price tag to the system that we had to abandon the fully reusable concept because of a budget squeeze. And that led to solid-rocket boosters, an expendable fuel tank and an orbiter that thrusts from launch-today’s space shuttle.

Yes, it’s a great technical achievement, but it really wasn’t built for operational simplicity, economy or reusability. By insisting on a manned booster, NASA priced itself out of the system it really should have developed in the early 1970s.

Today, I see the same problem in the struggle over the space station. It’s either all or nothing—nowhere could replace the aging main core module and perhaps attach a living facility such as the commercially financed Spacehab module.

Then, in the same orbit, the United States could build a laboratory that could attach to and detach from the permanent facility. The sustained human presence in space would remain there, but the stillness you want in a laboratory would be preserved without human disturbance.

Speaking of stillness, about 10 years ago I commented that the space program’s most desirable space station already has six American flags on it. And Isaac Asimov once pointed out that the Moon is the slowest moving object in the solar system. With its thermal stability and freedom from radio interference, the Moon beckons as a marvelous venue for space science.

But I also think that a return to the Moon offers a way to leverage an evolutionary expansion of our capability in space a way that’s more likely to sustain itself than to drift in an ebb and flow. To that end, I foresee a scheme in which, first, a heavy-lift rocket with reusable strap-on boosters goes directly to the lunar surface, rather than performing a lunar-orbit rendezvous as we did in Apollo. Reusable flyback boosters, by the way, could also expand the shuttle’s capabilities.

That done, you graduate to even more reusability. Moon-bound astronauts could transfer to a reusable lander at Lagrange point Li, the stable region just off the Moon’s near side where lunar, solar, and terrestrial gravity balance out. On the way home, they might switch back to an Earth-return vehicle parked at L1. You could even store propellant made from lunar materials at Li.

Once you have that capability, you have the foundation for sustained evolution. You have a system for assembling more ambitious projects—Mars convoys, for example. I still believe that orbital assembly is the most appropriate way to build an infrastructure for Mars exploration.

Thomas Paine, NASA’s administrator during my days in the program, envisioned a permanent human presence on the Moon that burgeoned gradually, from four people to eight to 100 or more. But if you project 100 years into the future, it’s quite possible that automation and virtual reality will make it unnecessary to sustain large numbers of people on the Moon. We might not even need a permanent presence on the lunar surface, as long as astronauts could get there on short notice to fix things.

After all, the Moon is not that far away. But to get from here to there requires a different kind of commitment than the one that put us on the Moon a quarter-century ago. Apollo was a glorious rush—one giant leap, as Neil put it. Today we need to take many small steps, each one leaving footprints that others can follow. One day, perhaps that path will lead to a fresh set of footprints at the magnificent desolation we called Tranquility Base.

You Might Also Like