Why Wilmington's neighborhoods aren't created equally when it comes to handling the heat

Editor's note: This article is part of a USA TODAY Network reporting project called "Perilous Course," a collaborative examination of how people up and down the East Coast are grappling with the climate crisis. Journalists from more than 35 newsrooms from New Hampshire to Florida are speaking with regular people about real-life impacts, digging into the science and investigating government response, or lack of it.

****************

Having escaped most of the ravages of the Civil War that engulfed other Southern port cities, Wilmington’s downtown is full of stately historic homes, often on brick streets and bathed in shade from hundreds of mature hardwood trees.

Altogether, the Port City has nearly 900 structures that have earned downtown a place on the National Register of Historic Places.

The city’s Southside, though, is not this Wilmington.

Here, concrete pads play home to old manufacturing buildings amid low-slung, tight homes built to house working-class and low-income families. Pockets of redevelopment are scattered among the buildings, many with protective iron bars on their windows. And many of the trees scattered around the working-class neighborhoods aren’t tall hardwoods, but bushy crepe myrtles that top out at roughly 25 feet.

On steamy summer days, there aren't many places to seek relief from the oppressive heat.

“Stay inside if at all possible,” said Bob Franklin as he walked to a bus stop on Greenfield Street, attempting to cut through the soupy late July weather with his hand.

So how does he try to stay cool on days like this?

"I don't," Franklin said. "I endure."

Poor planning decisions

Heat and humidity are a time-honored tradition to be endured in North Carolina. But something else is now happening.

Climate change is warming the planet, and summer temperatures. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), temperatures in North Carolina have risen 1 degree Fahrenheit since the beginning of the 20th century. If things don't change, and quickly, the United Nations predicts global temperatures will rise by several more degrees by 2100.

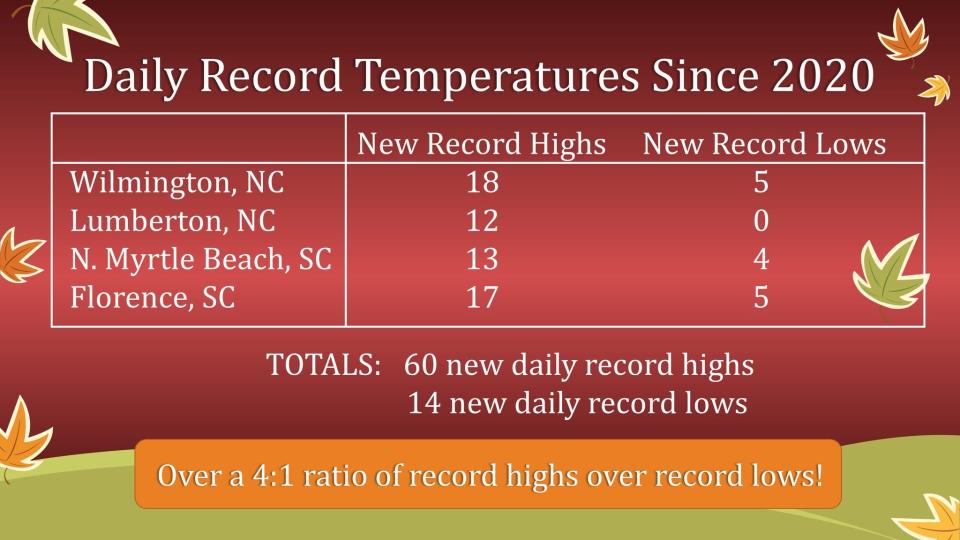

Already, warming temperatures are being felt across the Cape Fear region. Earlier this summer the U.S. National Weather Service in Wilmington reported that Southeastern North Carolina and Northeastern South Carolina had recorded 60 new daily record highs since 2020 compared to 14 new daily record lows.

RISING WATERS: 'Undergoing a transformation': How increased high tide flooding could reshape the NC coast

The First Street Foundation, a New York-based research and technology group focused on climate change risk, forecasts things to get even worse in the coming decades. A hot day in Wilmington is considered to be any day above a “feels like” temperature of 104 degrees Fahrenheit. Wilmington is expected to experience seven hot days this year. Due to a changing climate, Wilmington will experience 19 days above 104 degrees in 30 years, according to First Street. And thirty years ago, the likelihood of a three day or longer heat wave in Wilmington was 14%. Today it's 50%, and First Street estimates that number will rise to 86% in 2050.

But American cities, including Wilmington, weren't built to handle the warming climate.

"We didn't build cities with this kind of heat in mind," said Dr. Ashley Ward, a senior policy associate at Duke University who focuses on climate health issues. The post-World War II shift to designing neighborhoods around cars instead of people has added to problems associated with older building materials and practices, like wide roads made of heat-sucking asphalt, that retain and then radiate heat back out.

"And now we're paying for those poor urban planning decisions," Ward said.

Not just 'another hot day'

Of particular concern in cities are urban heat islands, areas where unshaded roads and buildings gain heat during the day and radiate that heat into the surrounding air, leading to "hot spots" that can be several degrees warmer than surrounding areas cooled by trees, open spaces or less-dense development.

And like many factors from economic, political, historical marginalization and lack of investment that separate the Port City's well-to-do and struggling neighborhoods, extreme heat in the city isn't distributed evenly or equitably.

WIND AND WHALES: For highly endangered North Atlantic right whales, offshore wind brings a lot of unknowns

Case in point is Greenfield Street on Wilmington's Southside. With heat emanating off the concrete buildings and asphalt road and cooling vegetation and open spaces in short supply, a temperature check showed it to be 104 degrees just before 1 p.m. on a sweltering July 28. A similar temperature check in Wilmington's leafy Forest Hills neighborhood, 7 minutes and 2 miles away, showed the temperature to be 97 degrees.

According to the National Weather Service, the July 28 high in Wilmington was 96 degrees. The city's official thermometer is at the Wilmington International Airport. The day fell during a 19-day window, from July 24 to Aug. 11, where every day except Aug. 7 had a high of 90 degrees or more, according to the weather service.

"Heat islands are a major health and social concern because of the cumulative effects over time," Ward said, noting the litany of health problems that prolonged exposure to hot weather conditions can cause.

Among the biggest emerging problems worrying researchers is the lack of "cool-down" time for buildings and humans due to temperatures staying much warmer at night. Over the last century, night-time temperatures have been rising faster than daytime temperatures across most of the world. This is because warmer air holds more moisture and the extra clouds reflect heat in the day and trap it at night. Humid nights are dangerous because it makes the body work harder to stay cool, putting a strain on organs such as the heart. A new international study, which included researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, predicts that deaths associated with excessively hot nights could increase by up to 60% by 2100.

BRIDGE TO THE FUTURE: Is new Rodanthe bridge the future of NC 12 on the Outer Banks?

"Heat is a serious problem," Ward said, noting that heat-related problems kill more people than any other weather event, "but we haven't treated it as a serious problem across the board.

"When we think about heat, we can't think that it's just another hot day."

The power of trees

For Wilmington, though, there's a big problem; city officials don't precisely know where the Port City's hottest urban hot spots are.

They have ideas, based on previous work by the University of North Carolina Wilmington and other groups, satellite data, and general knowledge of how structures, concrete and impervious surfaces influence local micro-climates.

"It's kind of a no-brainer," said Chad Cramer, a city urban designer, on what parts of Wilmington heat up the fastest. "But we do need to get that specific data."

Other North Carolina cities, notably Raleigh and Durham, have engaged universities, government agencies and volunteers to fan out and use heat sensors to create urban "temperature" maps.

Wilmington officials say they'd like to do the same, but funding and organizing such a program remain potential obstacles.

That's left city officials chipping away at the problem best they can.

The Wilmington Tree Initiative, a public-private partnership, has planted or given away nearly 13,000 trees since September 2020, partly to replace those lost to the rash of hurricanes and tropical storms the Port City has endured since the mid-1990s.

"The multitude of benefits you get from a tree just can't be overstated," Cramer said, ticking off shading, absorbing stormwater runoff, and beautification as just a few of them.

BOY SHORTAGE: NC sea turtle nests could be producing fewer males. Here's why that's a huge problem.

City officials are also working on several plans to promote and incentivize more walkable developments. Green-building practices are being encouraged, and officials are exploring ways to fund — whether through local, federal or grant mechanisms — more parks and open space projects to break up the expanses of impervious surfaces.

Where possible officials also want to retrofit existing neighborhoods through streetscape projects and adding green areas to make them more pedestrian friendly, appealing, and less heat absorbent.

"It's possible, desirable, and one of our goals," Cramer said.

But many of those initiatives takes time, money and community involvement — all of which are in short supply in areas like Wilmington's Southside.

Sitting on the curb in front of the Family Dollar across from the Houston Moore public housing community, LaToya Howard said there's only so much working-class folks can do to battle the heat.

"Our electricity bill is already high, and when you're on a fixed income there isn't much wiggle room to begin with," she said when asked if she would crank the air conditioning to stay cool, adding that she has a donated fan but blowing hot air only does so much.

Without a car, Howard said, it isn't easy to organize trips for her and her children to a city pool or splash pad, the mall or public buildings to help them escape the sticky, hot weather.

"Sometimes you just feel like you can't cool down, even at night," she said. "It just makes life harder than it already is."

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Why Wilmington neighborhoods aren't impacted by heat evenly