Wichita’s forgotten hero of the Lost Battalion — and how local veterans are honoring him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

One day, long ago, a daring young flyer from Wichita devised a plan that made his fellow flyers cringe. A suicide mission, they said.

Erwin Bleckley and his pilot, Harold Goettler, climbed into their warplane anyway. They had already been shot at — thousands of bullets from German rifles and machine guns — while trying to locate the so-called Lost Battalion. The Yanks, or Doughboys, as they called themselves, were roughly 550 guys surrounded in a French ravine, starving four days so far, shivering in rain, dying from explosions and bullets. The one thing they had going for them, said the historian Robert Laplander, was their fellowship of soldiers.

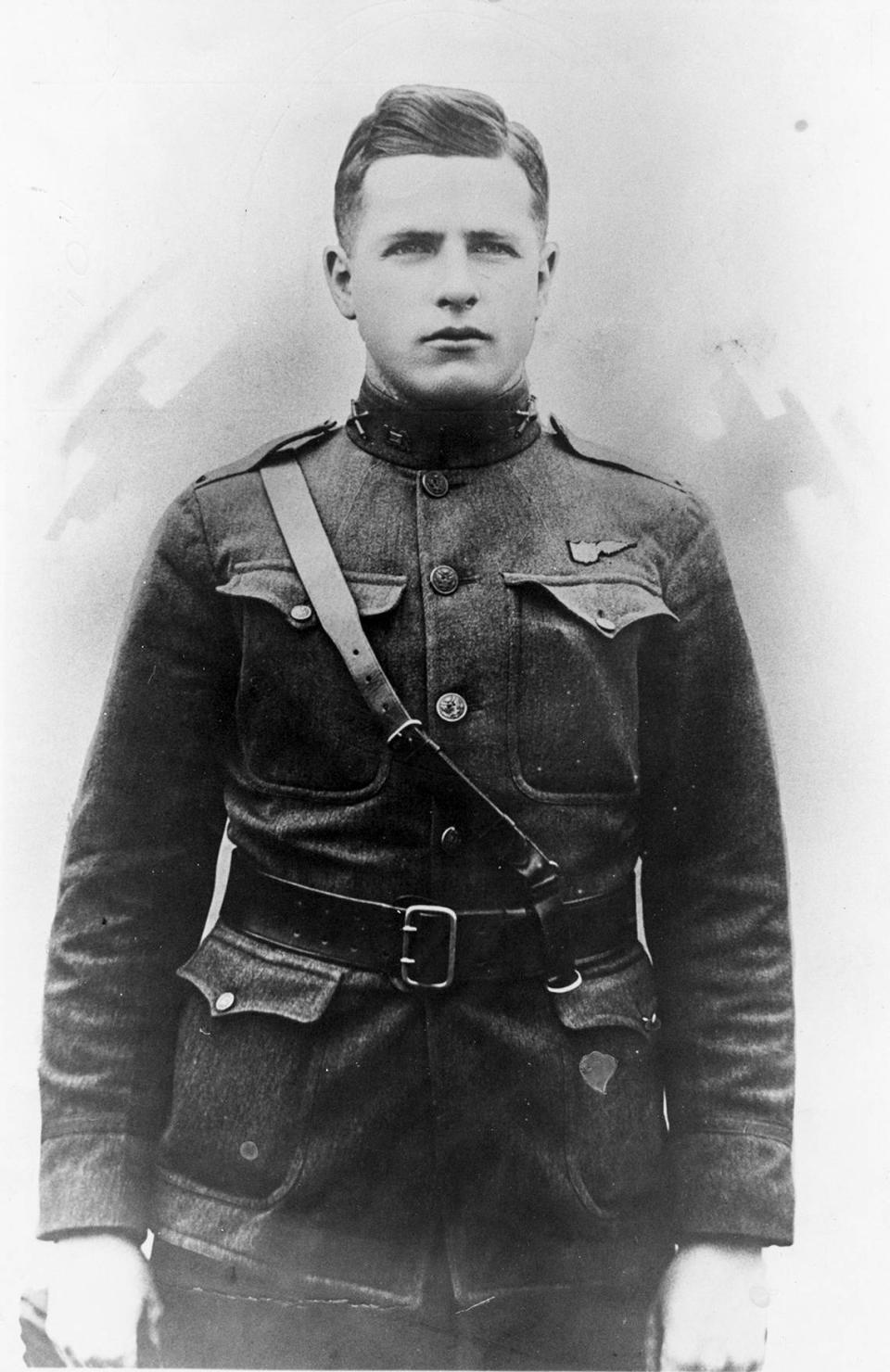

Bleckley was 23.

The last thing the Wichita kid said, before he and Goettler took off, was to squadron commander Lt. Daniel Morse. Goettler had already cranked their DH-4 engine into a roar. Morse, so Bleckley could hear him, climbed up the side of the airplane and put his mouth where it almost touched Bleckley’s ear: “Good luck and be careful.”

“Don’t worry, lieutenant,” Bleckley said. “We’ll find ’em or we won’t come back.”

What Bleckley and Goettler did in 1918 earned both of them the Medal of Honor. It was selfless, clever, and more dangerous than even their fellows had thought. But as time passed in our distractable culture, what they did has been mostly forgotten.

One hundred years later, two old soldiers from Kansas said they’d see about that.

Carrying memories

America has 18,250,044 living veterans, according to the Veterans Administration. Of those, 5,624,418 have a service-connected disability. There are 182,120 veterans who live in Kansas, and 33,020 who live in Sedgwick County.

Most did not see combat. Many did. Unless they wear old uniforms, we pay them no mind.

Greg Zuercher from Wichita led infantry soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. One guy he led, Army Sgt. Jessie Davila from Dodge City, was killed in Baghdad in 2006. Zuercher says he carries Davila’s name in memory, along with Erik McCrae, a friend, an infantry lieutenant from Oregon, only 23, who earned a degree in applied physics and died in Iraq, killed by a roadside bomb.

Zuercher entered the insurance industry after service; it gave him income and purpose, but not high purpose.

He missed the fellowship. So, he joined Wichita VFW Post 112 after he left the Army in 2013. He became a junior commander, “whatever that means.” In 2018 members talked about what they might do to help or inspire fellow soldiers.

Zuercher said: “What about doing something to honor Erwin Bleckley?”

And the other old soldiers said: “Who?”

Charlevaux

What Bleckley and Goettler proposed was that they fly their plane as low and slow as possible over the ravine holding the Lost Battalion — and deliberately draw German gunfire.

The French named the ravine Charlevaux. Bleckley and Goettler had already flown through it once that day: Bullets tore through fuselage and wings. One bullet whacked into the machine gun that Bleckley fired from the back seat.

“Bleck” and “Dad,” as fellow flyers nicknamed them, were anxious to find and resupply the battalion by dropping food, chocolate and bandages out of their airplane.

The Army — and the newspaper-story-addicted American public — were anxious that those soldiers be rescued. They felt this way in part because Damon Runyon, a gifted, reckless, chain-smoking New York journalist, (born in Manhattan, Kansas) had got French mud smeared on his nice duds as he reported the battalion’s plight from near Charlevaux Ravine. We say “reckless,” because Runyon, who later became famous by hanging out with Mob hit men and crime bosses, crawled to within 20 yards of enemy German foxholes, the historian Robert Laplander said; he wanted a front-row view.

The first story Runyon wrote on Oct. 5 prompted a telegraph reply from Harold Jacobs, his Hearst boss across the Atlantic: “Send more on Lost Battalion.” The Doughboys hated that name, by the way: “We were never lost. The whole Germany army knew where we were the whole time.” Wire services put Runyon’s stories all over newspapers. Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing, the American commander, demanded rescue.

Charlevaux Ravine was only a fragment of the Meuse-Argonne offensive that started four days before, in northeast France. The Americans and French proposed to finally break the exhausted German Army.

They did break them. The war would end in five weeks. But 26,000 Americans died in 47 days. “The worst battle America ever fought,” Laplander said.

The Lost Battalion epic began Oct. 2 when Maj. Charles Whittlesey, a bespectacled New York attorney, led his battalion forward near the village of Binarville. Whittlesey and his Doughboys broke German entrenchments and advanced into Charlevaux Ravine. But the American battalions on either side of Whittlesey’s battalion were shot up; their forward movement stalled, leaving Whittlesey’s Doughboys isolated.

Bleckley’s 50th Aero squadron couldn’t easily find Whittlesey’s Yanks from the air. “When the trees leaf out, sunlight there never touches the ground for months,” said Laplander, who has walked there many times. “It’s jungle-like, dense. I can’t think of a worse place for open warfare.”

Whittlesey’s boys (many were teens) dug holes into the side of the ravine to hide from bullets that were snapping off limbs and spiking up mud. By Oct. 6, when Bleckley and Goettler flew their two flights, Whittlesey’s Yanks had starved and shivered for four days.

Two days before, on Oct. 4, American artillery shelled them by mistake.

Whittlesey wrote a note. An officer stuck it onto the leg of their one remaining carrier pigeon, a bird named Cher Ami. Cher Ami was knocked down by a shell fragment when he took off. But he got up and flew onward — with a hole in his breast, and now missing one eye and one leg.

“Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us,” Whittlesey wrote. “For heaven’s sake stop it.”

By then his living Yanks were peeling bandages off dead Yanks to bandage wounded Yanks bleeding in autumn rain. Germans had killed or wounded hundreds. Bullets flew so constantly that men stayed in their “funk holes,” as they called them — not daring to rise even when they went to the bathroom.

On their first flyover on Oct. 6 Bleckley thought he saw an American uniform, and maybe one Yank laying out a signal panel to show their location. He and Goettler flew back to base with French air whistling through 40 holes in their DH-4. “They got the hell shot out of them on that first trip,” Laplander said.

“I think we can find them now,” Bleckley said.

They grabbed another plane, numbered with a big red 6 painted on the fuselage, alongside the mascot painting of “The Old Dutch Cleanser Girl.” Fellow flyers watched with dread.

This time, Bleckley said, instead of zooming through, they would fly just above stall speed — and under 200 feet, only yards above treetops — so low that Germans on ridges surrounding Charlevaux would point their rifles downward to shoot. “Madness,” said fellow flyer David Beebe, when they told him.

But Bleckley said he could then mark on a map showing which patches of Charlevaux were not shooting at them — and which patches blinkered with bright-orange gun blasts.

Beebe ran the idea past squadron commander Morse. “Morse just kind of stared at them,” Laplander said. “He thought it was suicide.”

The most knowledgeable authority on the Lost Battalion and Bleckley’s heroics is Wisconsin author Laplander.

Laplander said Morse OK’d the plan “because he realized that this was the only idea that was going to work to find those guys.”

There was also some war romanticism at play, Laplander said, rolling his eyes. “Everybody over there was saying that this was The War to End All Wars — that it was so horrible that it had to be the last one. So, there were lots of people who thought these last months would be their only chance to do something heroic.”

Morse approved the plan. Bleckley went to his tent and wrote a last will. “He put those guys in that ravine above himself,” Laplander said.

For thousands of years people have asked heroes why they charged toward almost certain death.

Survivors almost never say: “Flag,” “cause” or “country.”

They say: “I fought for the guys beside me.”

Primitive, deadly planes

Bleckley’s Wichita parents, Elmer and Margaret Alice Bleckley, had begged their son, when he volunteered in 1917, that he not become a combat pilot — what he wanted.

Author Quentin Reynolds researched World War I aviators to write his book “They Fought For The Sky.”

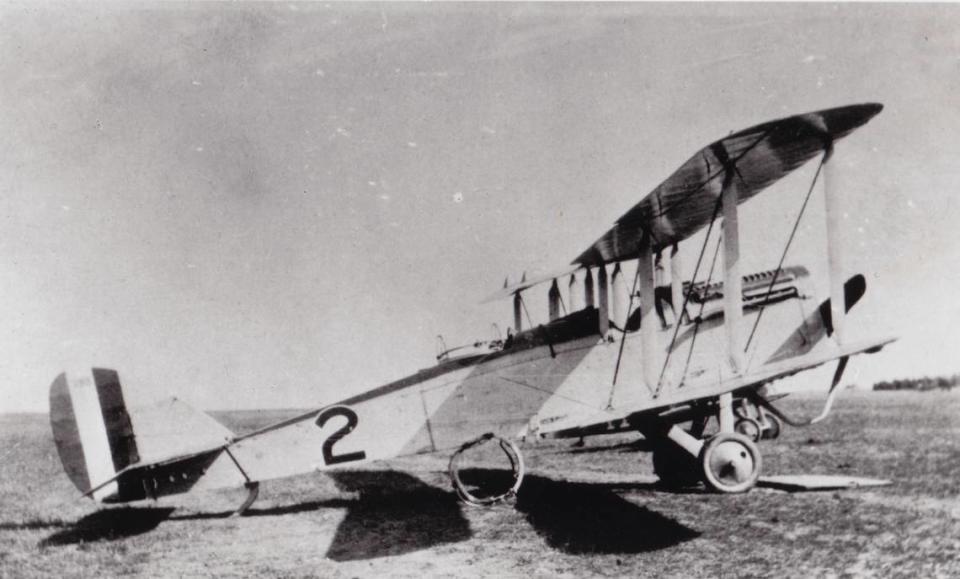

Airplanes had been invented only 14 years before Bleckley volunteered. They were primitive. “Flying kites,” pilots called airplanes. “Flying bird cages.” Thin, pinewood puzzle pieces overlaid with thin wires — and canvas skin that burned like a meteoric flying inferno if ignited. “At that time, being a combat pilot was considered suicide,” Laplander said.

Pilots adopted stylish goggles, long neck-scarves and a swaggering style. Germany’s “Red Baron” flew his red triplane with the black Iron Cross emblems painted on his three wings. Bleckley’s squadron painted their De Havilland biplanes with the blue-and-white “Dutch Girl,” an image advertising a pumice-based cleanser that scoured dried blood off slaughterhouse floors. The squadron “Dutch Girl” image evoked “Cleaning up on Germany.”

There were no parachutes. “Some thought that if you gave pilots parachutes, they might get scared early and bail out,” Laplander said.

Elmer and Margaret Alice Bleckley of Wichita had no doubt read about these dangers in The Wichita Daily Eagle.

Combat pilots survived, on average, only two to three weeks before dying in burning infernos plummeting to Earth, as Reynolds wrote. Flyers carried handguns — to resist capture, and to shoot themselves if the plane ignited. Nobody wants to burn.

Movies show World War I pilots shooting machine guns at each other. But no pilots shot down any planes in 1914, World War I’s first year.

Enter Roland Garros, Reynolds wrote. France’s most celebrated stunt pilot before the war hated Germany so much that in early 1915, he mounted a machine gun behind his propeller and began to shoot down German planes, the first pilot on either side to do so.

The shocking part: While most of his bullets passed through his whirling propeller, some bullets hit it. To avoid suicide, Garros had bolted triangular steel wedges on the inside faces of his propeller blades, hoping, betting his life, that the wedges would deflect bullets.

Pilots who mimicked Garros ended up dead. But Garros survived three more years — as a prisoner of war. His fuel line clogged one day; he landed behind German lines; Germans served champagne to the captured pilot — toasting his bravery.

One day later, Reynolds wrote, Tony Fokker, a Dutch mechanic working for Germany, looked over Garros’ warplane, declared the gun-propeller innovation suicidal — and invented a machine gun with a timing device tied into the propeller. Fokker’s gun fired bullets through the propeller that never hit the propeller.

German fighters then shot down most of the French and British air forces. But after a German plane was captured, French and British mechanics mimicked Fokker’s innovation. After that, pilots on both sides died by dozens — usually in meteoric burning infernos — but not by blasting their own propellers into toothpicks.

He promised

To calm his parents, Doug Jacobs said, Bleckley gave up his fighter pilot idea; he volunteered instead for the artillery, which, on paper, seemed less risky.

Jacobs, a retired soldier, has spent decades studying Bleckley.

Once in the military, learning how to fire big guns, Bleckley soon gravitated to artillery “observation,” which brought into play Bleckley’s math skills, Jacobs said. At Wichita High School, where he graduated in 1913, Bleckley was good at math, besides being (according to the school yearbook), popular with girls.

Artillery observers used math to plot enemy location coordinates so their own artillery can hit the enemy accurately. Observers were not often front-line fighters. Learning this, Bleckley’s parents might have felt not only relief but pride.

But Bleckley soon learned that observers had embraced a new innovation: From the second seat in two-person airplanes, they flew over German lines, plotted enemy locations on maps, then flew over their own lines, dropping messages from the sky that contained enemy location coordinates.

So while Bleckley had not, in fact, volunteered for combat aircraft, he may as well have.

Here are three relevant facts that Reynolds wrote about World War I aviators:

Mick Mannock, the greatest British ace, (61 Germans shot down) flew too low one day and died from German rifle ground fire.

Germany’s “Red Baron,” Manfred von Richthofen, the war’s greatest ace (80 kills), died from ground fire.

Frank Luke, the first Yank pilot to earn the Medal of Honor (18 kills) died when German soldiers shot him on the ground. But he was on the ground because he’d been wounded by ground fire while flying low.

His own money

“It is absolute travesty that Erwin Bleckley has been mostly forgotten in his own hometown,” Jacobs said. “And Greg and I are going to do something about that.”

Jacobs said this with vehemence not long ago in an Old Town Wichita warehouse. There, he, Zuercher and friends are rebuilding a De Havilland (DH-4) two-seat biplane identical to Bleckley’s.

It’s not a replica. Their plane is constructed mostly with De Havilland parts left over from World War I, Jacobs said. Part of the frame and wing slats are made from new wood — but from Sitka spruce, the same wood in Bleckley’s Dutch Girl.

The people rebuilding it are unpaid volunteers, some of them veterans, drawn from Wichita’s considerable pool of aircraft workers. They will rebuild it strong enough to fly, Jacobs said — but probably won’t fly it. They hope instead to display it, in all its 42-foot wingspan and Dutch Girl glory, alongside a life-size sculpture of Bleckley, inside Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport. Thousands of passengers will finally see the man that Zuercher calls “the most significant flying hero in Wichita history.”

The airport idea is so far just an idea. When the guys first approached the Wichita City Council in 2020, airport authority officials politely stated that there is currently no room in Eisenhower for a display that size. Talks are ongoing.

Jacobs is 72. Like Zuercher, (age 65) Jacobs spent decades in uniform — 34 years, mostly in the Kansas National Guard, but several years on active duty, including as a peacekeeper in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a hazardous duty zone when he served there.

Zuercher has donated roughly 1,000 phone calls, and another 1,000 emails, and seemingly endless planning and advocating to the cause. So far, Jacobs has spent $107,000 of his and his wife’s money. When they bought the De Havilland to rebuild it, the price was $105,000. Two other Bleckley admirers, Grant Schumaker and his wife, Katherine Schoessler, a former Wichita couple, have given $48,000 to the cause.

All this might seem borderline obsessive.

“No, no,” Zuercher said. “Not obsessive. We just want to honor a fellow soldier.”

They continue to solicit donations — and say they could use the help.

Obscenities

And here is a glimpse of the Doughboys that Bleckley tried to save, as told to us by Laplander:

By Oct. 6, 1918, the day Bleckley and Goettler flew their two bullet-blasted missions, the Lost Battalion commander Whittlesey had listened to wounded Doughboys sob and scream for four days and nights.

They were mostly New York teens or early twenty-somethings. So many were immigrants to America that when German riflemen overheard Yanks talking in the ravine, they thought they had tangled with Italian soldiers.

The Doughboys were so hungry by Oct. 6 that they were chewing Army-issued wax candles meant to give foxholes a little light. Lying in rain had started foot-rot. Trigger fingers no longer bent. Knees stiffened; Doughboys worried they could not stand up anymore. Many had wounded legs and arms infected with the flesh-rot of gangrene that would kill them, or force amputations.

And yet the Dutch Girl planes made Doughboys swear out loud.

Laplander tells what the Doughboys saw:

Bleckley and Goettler were one crew of several from the 50th Squadron trying to help. Doughboys saw several Dutch Girls criss-cross over them on Oct. 6.

The Doughboys swore obscenities because every flyer, including Bleckley, dropped supplies over the side; but every can of stew, every bandage packet, every bar of chocolate landed beside laughing German riflemen. Laplander reported:

“Hey, Yanks,” Germans called out in English. “Good stuff in the boxes! Bully beef, hard bread and canned stew? What will we do with all this food? It is much more than we need. Are you hungry, Yanks? Perhaps, you would care to come up here and join us?”

A spring-fed stream watered the ravine, but when Doughboys reached puddles, they died, or ran back to hidey holes with holes in canteens. Some German snipers were so fluent in soldier English that they yelled: “Get up, let’s move! We’ve been relieved!” Yanks stood to obey. Snipers killed. Boys screamed. Snipers laughed.

“Bandages and medicines? Whatever is the matter? Are you hurting, Yanks?”

“Why haven’t I heard about this guy?”

Jacobs grew up in Liberal, Kansas. Like Bleckley, he has a head for numbers, and became an officer in charge of finances for large units.

He read a magazine story in 1994 that mentioned some kid from Wichita who started in the Guard artillery and ended up a Medal of Honor aviator.

“The Medal of Honor for a National Guard artilleryman? That piqued my interest.”

By the time Zuercher reached out to him five years ago, Jacobs was a Bleckley authority. He collected hundreds of pages of documents, magazine and newspaper stories. He photocopied Bleckley’s war diary, which lay in the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

He contacted Nancy Bleckley Erwin, Bleckley’s niece, born 1933. To her delight, she found that he knew more about Uncle Erwin than she. The first thing Nancy and her son Mike Erwin say when contacted is how grateful they are that Jacobs revealed to them the hero their family had mostly forgotten.

Scarecrows

Maj. Whittlesey thought by Oct. 6 that his Yanks might surrender, or desert against orders. He overheard traumatized boys talking in tones of despair. He had counted: 70% casualties.

But then an extraordinary thing happened, on both Oct. 6 and 7, Laplander said:

The Germans blasted them with artillery, tossed grenades, then charged: Hundreds of Germans fixed bayonets and raced toward sick Doughboys soaking in mud. The Germans screamed obscenities, fired rifles, lit fuses on flamethrowers.

But Whittlesey watched in stunned disbelief on both days as his Doughboys rose up on quivering legs. And THEY charged. Dozens of his filthy, foul-smelling boys raced forward without orders, yelling like banshees, shooting Germans left and right, calling names that disgraced German mothers.

Germans ran for their lives. Yanks shot them in the back, shot the flamethrower Germans; and when one German burst into flames from his flamethrower, no Yank felt sorry.

Whittlesey and his officers had to yell and yell at their scarecrows to come back, Laplander said. They did turn back, not right away, and some didn’t stop screaming obscenities for 20 minutes. Few had any bullets left.

Whittlesey feared his boys might do suicide charges. But they fell back into their holes.

They would starve and sob in the rain for one more day.

Bleckley and Goettler never got to meet them.

He stayed

They should have grounded themselves, those two, after bullets rendered their first plane disabled. They could have celebrated German surrender 36 days later.

Bleckley had a fiancé, Enid Jackson, Jacobs said. Before he flew that second mission, he scribbled a note telling friends to let her know what happened. He likely patted his jacket pocket holding Enid’s picture over his heart.

People at Fourth National Bank, where Bleckley had worked alongside his father, probably would have helped that ambitious veteran to get into business — maybe in aviation, Jacobs said. Bleckley had done extraordinary work aboard warplanes under fire. Wichita would soon become an aviation magnet. Clyde Cessna had built his first airplane in 1911 near Rago, southwest of Wichita. Walter Beech would become a Wichita name.

Traumatized Yanks went home after the war.

Bleckley stayed in France.

A cool customer

Laplander’s narrative book is “Finding The Lost Battalion.” He gave us multiple interviews.

Just after 2:30 p.m. on Oct. 6, Goettler piloted their Dutch Girl into Charlevaux Ravine — below 200 feet, just above stall speed.

They passed back and forth as gunfire roared.

Laplander quotes an eyewitness. William Ettinger was a New Yorker, a volunteer ambulance driver for the American Field Services, working with French medics. Ettinger had a good view of the ridges and sky as he stood outside a wrecked cellar being used as a wound-dressing station. Laplander quotes Ettinger’s later letter to Bleckley’s friend Lt. Beebe:

“I was standing in the doorway…Watching a plane which was flying parallel to the lines…at what looked to be a particularly unsafe and low altitude. Standing with me were a couple of Frenchman, stretcher bearers … and we were discussing the probable identity of the plane, as none of us have ever seen an American plane before … German machine guns were giving him a great reception. Although subject to a constant and terrific firing from all sides, he continued, undisturbed, to fly up and down the line without any apparent objective … but on the contrary was drawing everybody’s fire for some distance around.

“He seemed to be patrolling a sort of beat … Certainly a cool customer.

“Until finally the plane, still at very low altitude, dove headfirst to the ground.”

“God help me…”

A machine gun bullet tore Goettler’s head off, Laplander said.

But that’s not when the plane crashed. Ettinger said the plane wobbled — then stabilized for a few moments — and then crashed.

Bleckley was not a pilot, but Goettler had taught him how to land, Laplander said. Bleckley likely grabbed his flight stick when Goettler died. What likely happened next was that Goettler’s body slumped, driving his stick forward.

“Three or four Frenchman and myself reached (them) a couple of minutes after he hit,” Ettinger wrote.

They found Goettler dead, entangled in wreckage. Bleckley they found yards from the plane. He was breathing, but unconscious; they saw blood leaking from devastating internal injuries.

Medics worked on him for 20 minutes, then told Ettinger to drive Bleckley to a field hospital 11 miles distant, at the village of Villers-Daucourt. “All I could think of,” Ettinger wrote, was: ‘God, help me to get this boy back in time to be saved.’”

Just outside Villers-Daucourt, Laplander said, a train rolled into Ettinger’s way.

Ettinger begged the engineer to move just a few yards. The engineer refused. As Laplander put it, the engineer had a schedule, and instructions, “and millions of his fellow Frenchmen had died in his traumatized country, and what was one more death?” After 20 minutes the engineer let Ettinger pass. But Bleckley had died.

Medics emptied his pockets, pulled out a blood-stained photograph of fiancé Enid Jackson.

The Army, on Morse’s recommendation, awarded Bleckley and Goettler the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest medal. In 1922, after the Army learned about Ettinger, they reached out. “I consider it the greatest act of bravery I have ever seen,” he told them.

Bleck and Dad were upgraded to Medal of Honor.

Pictures on the wall

Nancy Bleckley visited Wichita as a little girl decades ago. She was not a Wichitan, though her father, Clarence, was Erwin Bleckley’s brother. Regarding Clarence: Erwin had written his parents in 1918, Jacobs said. By then, Erwin had seen firsthand the massive scale of the war’s death toll. Keep Clarence out of the war, he wrote.

In Nancy’s grandmother’s house in Wichita there was a room with memories. Nancy remembers, as a child, studying a photo of a young guy. A picture of a medal.

Nancy learned one day, when older, that the guy looking so drop-dead handsome in the photograph had been her uncle — and some sort of hero. But no one in the family seemed inclined to say more.

This didn’t line up with the family dynamics, she said; in her family, love was evident. Everybody celebrated family.

Nancy later married a man whose last name was Erwin; so while her uncle was Erwin Bleckley, she became Nancy Bleckley Erwin.

She realized later, she said: The silence in that house was all about grief.

“Not in vain”

Squadron commander Morse wrote Erwin’s father, Elmer, shortly after Bleckley’s death, according to Wichita Eagle stories. Bleckley was born in a house at 609 St. Francis, but by 1918 the family lived at 111 N. Lorraine Ave.

“I wish to write you a few lines as his commanding officer, regarding the most heroic death of your son in action,” Morse wrote. “His mission at the time of his death was the most perilous one, and which he took with the wonderful spirit he had always shown went with the squadron. Your son’s death has not been in vain, Mr. Bleckley, and as much as we all lament it, it was given in the wonderful cause for which we are all in France, and from which none of us is shrinking. His gallant death in action is the most noble a man can have.”

Bitterness

Survivors like Enid Jackson moved on as best they could, Jacobs said. She married a Kansas City banker, R. Crosby Kemper Sr., Jacobs said. People from Kansas City still see her name associated with Kemper Arena, and with the charities and foundation she and her husband supported. Google “Enid and R. Crosby Kemper” and you will see much to admire.

Others didn’t fare as well.

The war killed reckless men like Roland Garros, who fired bullets through his propeller. In February 1918 Garros escaped from a German prison camp, returned to his French squadron and shot down another German warplane.

But on Oct. 5, one day before Bleck and Dad died, Garros was shot down dead, only 37 days before mud-caked German and French soldiers hugged each other at last.

The saddest sequel to the Lost Battalion story, Laplander said, is what happened to the most celebrated hero that Bleckley gave his life to save.

Soft-spoken Charles Whittlesey, who led those “lost” men, walked out of Charlevaux Ravine with his survivors on Oct. 8. The Yanks were so filthy that other Yanks smelled them before they saw them. Search YouTube for “Lost Battalion,” and you will see a few seconds of video of survivors walking out.

Whittlesey became nationally celebrated while sleeping through dreams where Doughboys sobbed. Widows, mothers and siblings came to his office, his home. Mothers asked: “Did my son suffer?” a question that prompted Whittlesey, an honorable man, to lie repeatedly.

His Yanks wanted help finding jobs, wanted to relive Charlevaux Ravine with him — to make sense of senseless suffering. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was not articulated until several wars later, Laplander said, but Whittlesey’s men had it. Their suffering made his worse. I am getting to the point where I can’t take much more of this, he told friends.

Whittlesey; his second-in-command, George McMurtry; an officer named Nelson Miles Holderman; Erwin Bleckley; and Harold Goettler were awarded Medals of Honor for their service in Charlevaux Ravine.

Praise did nothing for Whittlesey, Laplander said. He was asked day after day to give speeches, and because he was a kindly man, he spoke.

In an earlier battle, Laplander said, Germans fired poison gas, and Whittlesey breathed it. Whittlesey probably had tuberculosis, a big killer then; gas damage made it worse.

When the United States created the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Gen. Pershing summoned Whittlesey as one of six hero pallbearers in Arlington National Cemetery. That was Nov. 11, Armistice Day, 1921. Whittlesey stood through it staring at the ground. “I think it was right there that he made a decision,” Laplander said.

From Arlington, Whittlesey traveled; visited his father around Thanksgiving. He then went to New York, where he boarded the S.S. Toloa, a ship taking passengers to Cuba. At sea, Whittlesey seemed suddenly in good spirits.

In the lounge that night he had drinks and told the captain and others, once again, the story of the Lost Battalion. He seemed finally unbothered.

At 11:15 p.m., Charles Whittlesey, age 37, successful lawyer, celebrated soldier and national celebrity, excused himself from his shipboard friends. He walked out of the Toloa’s lounge and was never seen again.

The captain turned the Toloa around the next day and looked for Whittlesey’s body.

He saw only a vast, empty sea.

Embittered

Wichita made much ado about Bleckley at first.

A street in east Wichita was named Bleckley Drive in 1932, this honor requested by the American Legion, according to a Wichita Eagle story covering the commemoration.

At some point a small monument pillar was put up, but after a time it became yet another object gathering pigeon droppings. It stands outside the Veterans Administration buildings north of Kellogg. We went looking for it, and found it, but when we asked employees on the grounds where it was, they didn’t know.

The Army offered to bring Bleckley home, Jacobs said. But his parents, like many parents, opted to leave their son in France.

Margaret Alice Bleckley crossed the Atlantic twice to visit her son; Elmer could not bring himself to join her.

Erwin was buried first near the battlefield, but later reburied in Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, located east of the village of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon. Bleckley lies under a small white cross, as do 14,246 fellow Americans buried there. Most died in the offensive that put the German Army at last on its back.

What happened next is a further tragedy, Laplander said.

Soldiers struggled to find jobs.

The public decided the war had been a waste. European monarchs, wearing fancy clothing, sampling abundant wine cellars, indulging massive egos and armies, had contrived to get 20 million killed. For what?

By the early 1920s, demagogues were snarling again, and Americans read about it with bitterness. Only four years after the war, radicals led by former German Army corporal Adolf Hitler, attempted a failed coup to overthrow Germany’s democratic government.

“America didn’t want to hear about the war anymore,” Laplander said.

After Hitler came to power — only 15 years after Bleckley died — Germany’s sons marched again to the cadences of war songs. Laplander said German soldiers believed the Nazis, who said their army had not lost the war but had been betrayed by “the Jews.”

America lost 116,516 in World War I.

Americans buried memories, too. The first time Laplander visited Goettler’s grave in Chicago, while he prepared his book, he was startled to learn that the caretaker had no idea that his cemetery contained the bones of a Medal of Honor hero.

And this is how it goes, for Bleckley and Goettler and also, when we think about it, for living veterans in Wichita from the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam and other places we don’t remember or can’t find on a map.

Many living soldiers suffer physical symptoms of trauma.

But we must not exaggerate or embellish, Zuercher says. Many soldiers need our help, he said, but some soldiers are as prone to flaws and exaggerations as others. “The veteran, in the end, is responsible for his or her medical care, happiness and peace of mind.”

Most of us don’t put any thought into this. Life must be lived looking forward.

Unless, maybe, a couple of old soldiers come along to remind us.

The salute

“We are dust,” Jacobs said. “And you realize that we are all dust, dust to dust, when you stand at a grave.”

Of the 557 lost Doughboys Bleckley tried to save, nearly 170 were killed. Many lie buried with Bleckley in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery; Laplander calls the place “a beautiful garden of stone.”

“It’s not like veteran cemeteries in the U.S., which have many soldiers who died long after their wars,” Laplander said. “Those who survived for years — they had families, invented things, had grandchildren, made things, bought cars, had careers, lived full lives. But the guys in Meuse-Argonne? They didn’t do those things. They died thousands of miles from home, filthy, scared and in great pain. And so, I love what Doug and Greg are doing. Anything we can do — so that those guys get remembered — we should do that.”

In 1995, only a year after Jacobs discovered the first traces of Bleckley’s story, Jacobs and his wife, Paula, flew to Europe to help her World War II veteran father celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Allied victory in Europe.

They went to several commemorations. But they had another plan in mind.

Why did Jacobs later give $107,000 from his savings, his pension, his wife, from Social Security earnings, to make a memorial? It put his finances at risk, he said.

He tried a rational answer: “Bleckley deserves remembering.”

But perhaps that question is answered best by relating what Doug and Paula Jacobs did in 1995.

They arrived at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery on a clear day. “Absolutely beautiful,” Jacobs said.

They found Bleckley’s grave: A small white cross standing in green grass. It bore the words “Medal of Honor” in gold letters.

Jacobs wore his class A dress green uniform.

He had knotted a formal black tie around his neck. The insignia on his jacket epaulets bore the symbol of his rank: Lieutenant Colonel, Kansas National Guard. His left jacket breast bore his service ribbons and awards. Jacobs wore the garrison cap that officers fold over and tuck into their uniform belts when they take it off.

On his hands he wore white gloves, in which he held a wreath: Grape vines that Paula had woven into a circle to symbolize the circle of life. A silk sunflower in the center to symbolize Bleckley’s home. A red ribbon signifying sacrifice.

He laid the wreath on Bleckley’s grave.

“I said a little prayer, and Paula prayed with me,” Doug said. “Thank you for your service. Blessings to you. For your sacrifice for others. For doing it not for credit but because it was the right thing to do.”

“I then stood at the foot of the grave,” Jacobs said.

“In the field, you snap a salute quickly, right hand to eyebrow, then drop it quickly and move on.”

But Jacobs now gave the salute you see white-gloved honor guards make, just before one guard kneels and hands a folded American flag to a grieving family. It was the salute that the doomed Charles Whittlesey gave as a pallbearer at the first ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

“I came to attention,” Jacobs said.

“A number of people owed their lives to him.”

“I raised my right hand slowly, methodically.

“I slowly, deliberately brought the edge of my right hand to my eyebrow line — and held it. And then I slowly, methodically lowered my hand to my side.”

“We looked around.

“It was so incredibly beautiful. Blue skies, white clouds, and gold and green farm fields surrounding all those thousands of tombstones.”

“But what put a lump in my throat was that thousands of other identical small crosses radiated out from his. His grave was the focal point for all that we saw.

“Later, when I learned that Erwin’s mother had decided to leave her son buried there, I understood why. Because I had stood where she had stood. I saw what she saw.

“He lay there in a beautiful place, surrounded by thousands of his comrades.”

To donate to the Bleckley Foundation

By mail:

P.O. Box 782212

Corporate Hills Post Office

Wichita, KS 67278-9998

To donate by PayPal or credit/debit card: Call Greg Zuercher and inquire at 316-253-3806.

The foundation is also seeking volunteers. Aviation manufacturing experience is a valued skill, but not required.

Visitors are invited to the Foundation workshop, (where volunteers are rebuilding a vintage 1918 De Havilland airplane), on Mondays and Thursdays, 9 a.m.-noon at 359 N. Mosley in Old Town.