William Degan: A look back at a Quincy hero on the 30th anniversary of Ruby Ridge

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As a historian, I try to keep a personal distance from the events I write about. However, one event early in my career with the U.S. Marshals Service makes that difficult.

On Aug. 21, 1992, deputy marshals' encounter with a fugitive on a remote Idaho mountain caused 30 years of pain that hasn't gone away.

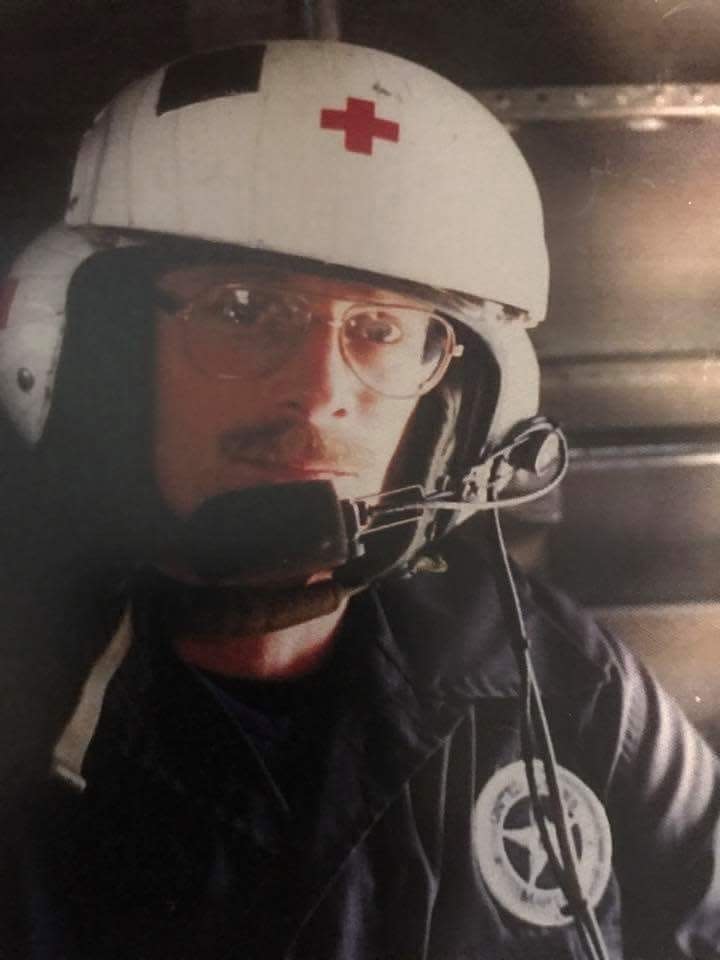

One of those deputies, William “Bill” Degan, was killed in the altercation. He was 42. Like the deputies, he was a member of the Marshals Service's Special Operations Group, which was founded two decades earlier to respond to emergencies.

Bill Degan was killed in a shootout with separatists Randy Weaver and Kevin Harris, as well as members of Weaver’s family. His death touched off a 10-day standoff between federal authorities and the separatists. Weaver's wife and son also were killed.

Weaver and Harris, who eventually surrendered, were charged in Degan's death, but they were acquitted of almost all the charges.

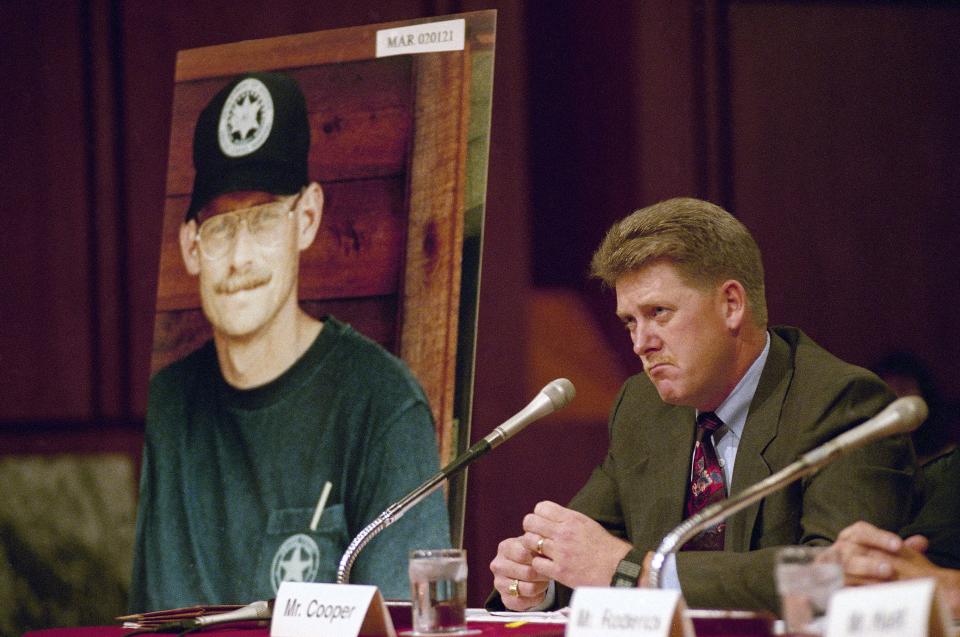

As I reviewed old papers and photos of the tragedy near Naples, Idaho, commonly known as Ruby Ridge, I was struck by several columns published during the September 1995 congressional investigation into the fatal confrontation.

Boston Globe journalist Thomas Oliphant pulled no punches in a Sept. 12, 1995, column, writing: “Three years ago, Billy Degan was murdered.”

Oliphant wrote that that the memory of Degan was "slighted" in the mire of the investigation.

“Billy Degan’s murder produced two acquittals and a standard death benefit for his widow and two kids,” he wrote. "That is disgusting."

Degan's widow, Karen Fitzpatrick Degan, watched the 1995 hearings. Although there were numerous mentions of his honorable service, she said her late husband’s career was lost in the tragedy of Ruby Ridge.

Degan’s eldest son, Bill, a deputy marshal himself, felt the same decades later. Ruby Ridge was a “national tragedy and, also, a very personal one for all involved,” he said. “The events of August 21, 1992, and subsequent days, ripped through lives across the country. They changed the course of history and severely impacted the lives of many people.”

Keeping Bill Degan's memory alive

For 30 years, the Degan family had remained publicly silent on the subject of Ruby Ridge. The family, including Karen, their two sons, and his two sisters, felt something needed to be said for the sake of posterity.

'A responsibility to remember': Quincy author's family history shapes WWII book 'Unsinkable'

Karen and Bill dated in high school and stayed married for nearly two decades. Their two sons were young when he died.

“His greatest source of pride were his sons, Billy and Brian,” she said. “Notwithstanding the absence of their dad’s physical presence, his sons nonetheless had the invaluable benefit of their dad’s loving guidance as they have grown to be fair-minded, compassionate and strong men. I know he is more than proud of his boys.”

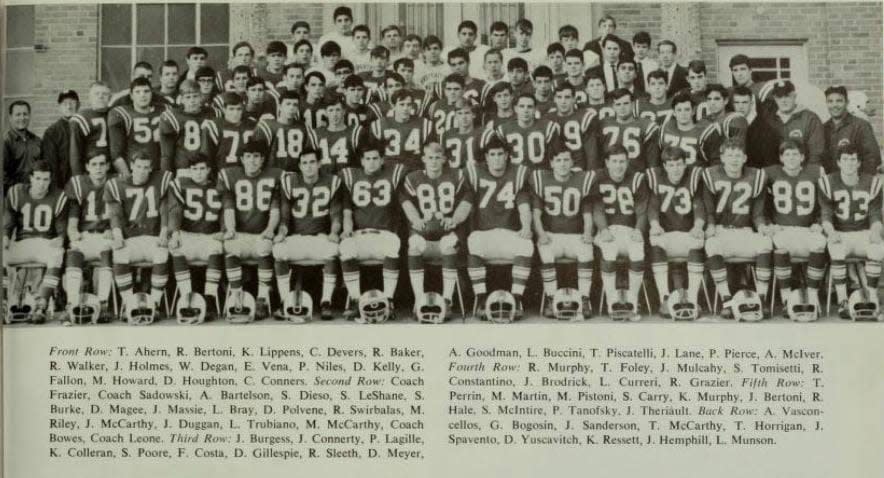

Degan was a North Quincy High standout

Bill Degan consistently overcame obstacles in his career on tasks big and small, whether it involved a post-hurricane rescue or moving a museum exhibit. Most of all, he was an honorable family man and colleague.

William Francis Degan was born on June 21, 1950, in Boston, to Bill and Marie Degan. His two sisters, Elaine and Sally, recalled their brother as an adventurous child who adored animals and sports.

He attended North Quincy High School. He excelled early, becoming a gym enthusiast and football star. It was there that he met his future wife. He attended the University of New Hampshire and was an All-Yankee Conference Team selection.

Prize-winning historian: For David McCullough, the South Shore became home

Degan graduated from UNH in 1972, and joined the U.S. Marine Corps as a second lieutenant in August. . His enlistment ended in August 1975, but he stayed active in the Marine Reserve until his death.

From Quincy to Cuba to St. Croix

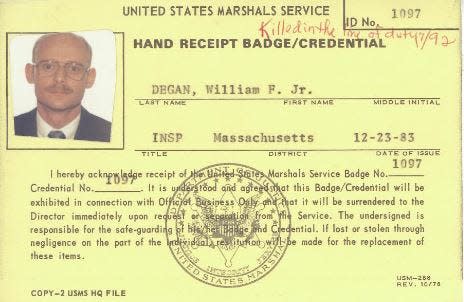

Degan joined the U.S. Marshals Service in January 1978. After his training, his first assignment was the Eastern District of Michigan.

His military service made him a natural to join the Special Operations Group later that year. Degan graduated first in his class. Graduation was difficult because of the intensive physical and tactical demands. Of the 193 deputy U.S. marshals who applied and pretested in 1979, 54 passed to take the actual course, and only 22 graduated. They received training in hostage and barricade situations, anti-terrorist tactics and emergency rescue.

What's in the water in Quincy? Documentary looks at city's history of patriotism, service

In March 1979, Degan transferred home to Massachusetts. His skill in special operations was tested in May 1980. Cuban President Fidel Castro had emptied prisons and sanitariums to complement a large group of refugees destined for the Florida coast. They were sent to detainment camps, where deputy marshals, including Degan, kept watch. The operation, popularly known as "the Mariel Boatlift,” sharpened his leadership skills.

Degan was a staff instructor in the Special Operations Group. In July 1981, he was promoted to task force commander, and two years later became a senior Special Operations Group inspector.

In a1986 mission in Puerto Rico, the Special Operations Group helped the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrest members of a terrorist group known as “Los Macheteros” (the “machete wielders”).

Three years earlier, the militia-like group pulled off the second-largest heist in American history at that time. A Wells Fargo security guard, aided by Los Macheteros, stole $7 million from a depot in New Haven, Connecticut. The guard fled to Cuba, and the base of Los Macheteros was in Puerto Rico.

The group was known for its violence, and claimed responsibility for bombings and assaults. Its intelligence network seemed vast, so Degan and the other 54 members of the Special Operations Group were told nothing of their mission until airborne.

Once in Puerto Rico, they secured the courthouse and readied cells for mass arrests. Over a three-day period at the end of August, they housed and transported the prisoners as they were extradited for trial.

Celebration: Quincy unveils bridge to honor generals and veterans on 20th anniversary of Sept. 11

Puerto Rico prepared him for an even greater challenge. After Hurricane Hugo passed through the Virgin Islands in September 1989, Degan became the Special Operations Group task force commander in St. Croix. He described the difficulties of staging a rescue mission there and told an interviewer, “It took three days to get transportation. There was no electricity in the downtown area and no phone service for the first full week.”

About 200 prisoners, some of them armed, had escaped. Degan's team spent the next month on the island.

In December 1989, Degan received a Director’s Special Achievement Award for his leadership in the rescue mission. He also received the Attorney General’s Award for Excellence in Law Enforcement in February 1991. His colleague Art Roderick called Degan one of the most “decorated and respected U.S. marshals.”

“When Billy spoke, which was rare, people listened,” Roderick said.

Retired U.S. Marshal Nancy McGillivray remembered Degan as a mentor. She said he was “gifted with a dry sense of humor, who always took the time to listen and provide valuable feedback.”

Of the nearly 300 U.S. marshals and their deputies who died in the line of duty during the agency’s long history, few are honored like William Degan.

The 37,000-square-foot William F. Degan Jr. Tactical Operations Center at the Special Operations Group headquarters in Camp Beauregard, Louisiana, was dedicated on March 12, 1993. On the first anniversary of his death, a moment of silence was observed, and flags were lowered to half-staff at headquarters and Camp Beauregard. A scholarship fund and an annual golf tournament are named in his honor.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the Federal Law Enforcement Dependents Act of 1996, which provided educational benefits to the dependents of law enforcement personnel who died or were disabled in the line of duty. Clinton specifically thanked Karen Degan for her efforts in creating the law.

Bill Degan remembered as a hero forever

Thirty years after Ruby Ridge, Degan remains a hero. His contemporaries saw him as the consummate modern deputy U.S. marshal, but for his family, he was far more.

“My father at work was a deputy U.S. marshal, but at home, he was a dad,” the younger Bill Degan said. “All of the work was set aside and he loved to spend time with his family. He taught me and my brother to fish, helped coach us up on our sports, and taught us to play golf at an early age.

"When I played youth football, he would give me pointers about running with the football and wrapping up when I tackled. He always volunteered to take my brother to 6 a.m. hockey practices. … We often vacationed with family on Cape Cod or in northern New England on the lakes. While there we would fish and play in the water all day. He was always there with us. … The saddest part about the whole tragedy is that he will never get to see his greatest work – raising two young boys to become grown men raised in his image.”

David S. Turk is the historian for the U.S. Marshals Service. He has written seven nonfiction historical books, including “Here Lies Billy the Kid” and “Forging the Star: The Official Modern History of the United States Marshals Service.”

Thanks to our subscribers, who help make this coverage possible. Please consider supporting quality local journalism with a Patriot Ledger subscription. Here is our latest offer.

This article originally appeared on The Patriot Ledger: William Degan: A look back at a Quincy hero 30 years after Ruby Ridge