Wing survey helps wildlife agency keep track of waterfowl

Of the million or so waterfowlers in this country, the federal government is so assured in my duck hunting talents that they regularly recruit me to participate in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Waterfowl Parts Collection Survey, and I am happy to answer the call.

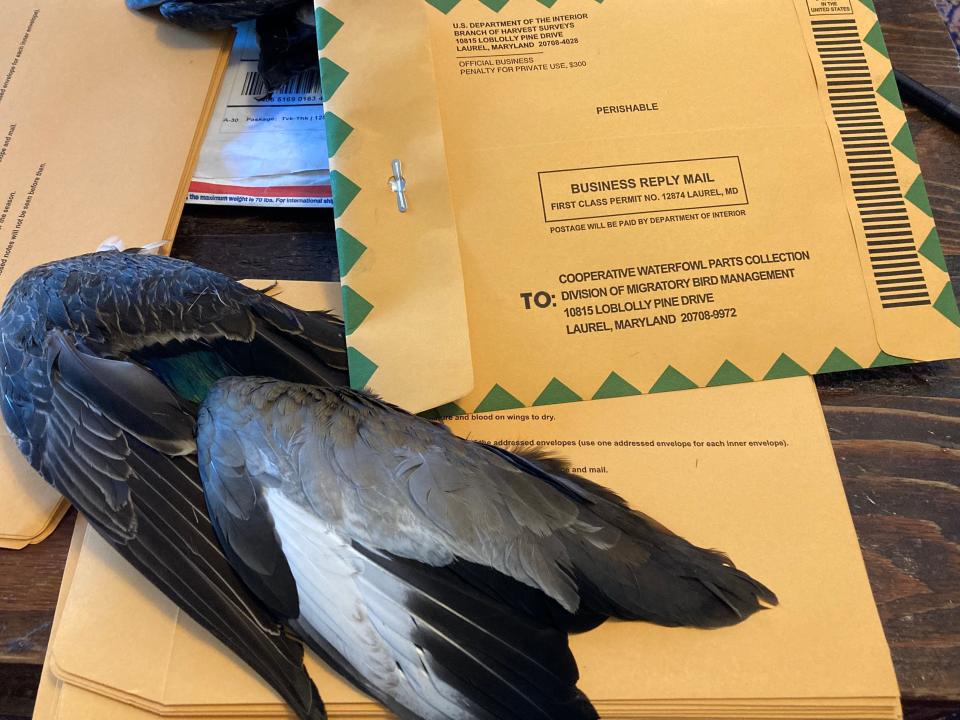

Also known as the Wing Survey, each season the USFWS solicits a sample of hunters to submit one wing from each duck that they shoot. The wings are carefully clipped from the bird and mailed to Laurel, Maryland for further examination. If all of this sounds like a stunt similar to kidnappers shipping a severed pinky toe to extort a ransom from a wealthy benefactor, well, we get postage-paid manila envelopes but no financial compensation for our efforts.

That’s fine, though, as this has larger purposes, beyond my humor in wondering if our mailman realizes what he’s toting in his satchel after he whistles away from my doorstep. Once safely in Maryland, the wing feathers are examined by state and federal biologists where they determine the species, sex, and age of the submitted specimens. This data helps the agency estimate the number of birds of different species in the year’s harvest as well as show how harvests trend over time and locations.

Why just the wings? In many species of waterfowl, the clearest differences between species, sex, and age is in the color of the feathers covering the middle of the wing, also known as the speculum. For example, mallards boast purple speculums; drake pintails sport iridescent green speculums while the hens have a dull bronze speculum. Or so I'm told as I don't really believe pintail exist since I can never find them, but I digress.

The duck's age is also assessed through variances in wing feather shape, color, pattern, wear, and/or replacement. According to the USFWS, this analysis allows the agency to calculate an age ratio (the number of young-of-the-year birds harvested per adult) for each species. These ratios are important because they are used to estimate reproduction during the previous breeding season. In a year when waterfowl production is high, hunters will bag more young birds than adults. This information helps set and justify bag limits during upcoming hunting seasons.

For 2021-22, I submitted 15 wings: two wood ducks, three mottled ducks, six black-bellied whistling ducks, three blue-winged teal, and one feral mallard. Of these, the feral mallard and one whistling duck were deemed adults. So much for that duck hunting talent I boasted about. And as any mean-spirited observer would point out, my small sample size isn't significant enough to extrapolate into any concrete conclusions, but it is another tile in the complicated mosaic that is waterfowl conservation.

No, the reason I’ve likely been asked to continue participating in this survey is my reliability in doing so. For a stretch of three years, I faithfully sent wings to Maryland before

term-limiting out. Guess they required submissions from duck hunting meccas other than Polk County, FL to keep their statistical models unbiased.

But, those manila envelopes arrived again for the 2020-21 season, and I was thrilled to be back in the game. This is another small example of how sportsmen can fulfill their roles as citizen-scientists that are critical in maintaining the country’s wildlife and establishing hunting seasons, subjects I never tire of yapping about.

So, if the feds come knocking at your door with a stash of envelopes asking you to ship waterfowl parts up I-95, don’t be alarmed. You’ve simply been selected for the Wing Survey because you’re in an upper echelon of the nation’s duck hunters, and the country needs your help.

Or, at least that’s what I tell myself. It's no more of a fantasy than a pintail.

For more information, please visit www.fws.gov/project/migratory-bird-parts-collection-survey.

This article originally appeared on The Ledger: Wing survey helps wildlife agency keep track of waterfowl