How Wisconsin educators are changing the way they teach to help kids' mental health

Ethnic studies teacher Demetrius Rice was midway through a virtual lesson when he noticed one of his high school students log on. The student was attending class in a Walmart breakroom.

Before the end of class, the student logged out to return to his shift.

It was the 2020-21 school year, the pandemic was raging and many of Rice's juniors and seniors at Vincent High School in Milwaukee were taking on jobs, falling asleep in front of their computers, or giving up completely on their education.

Rice is one of more than a dozen educators around the state that USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin reporters spoke with to understand how students are faring after the pandemic, and the shifting role teachers can play. This reporting is launching a new focus for our Kids in Crisis series, which examined children's mental health and Wisconsin's high rate of teen suicides from 2016 to 2018.

RELATED: You're Not Alone: A documentary and suicide-prevention toolkit

Future coverage will bring in the perspectives of students, to better understand their experiences.

Today's students are experiencing historically high levels of anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation. Wisconsin teachers said they're seeing that in their classrooms with the new generation of students, sometimes referred to as "Gen C" for COVID-19.

2023-24 marks the third full school year since the return to in-person learning, but the effects of COVID isolation and grief have been corrosive, rooting themselves deeply in young people who, even before the pandemic, struggled with mental health. That damage continues to grow and ripple through the lives of students and the classroom.

More: Wisconsin youths: More mental illness, more intense behavior, more suicide attempts

Math and reading test scores have plummeted, and test-score gaps between lower-income and higher-income students have grown even wider, according to the Brookings Institution.

When a student is struggling with their mental health, it often collapses any ability to absorb facts about math, history or grammar, educators say. That means it isn't just about finding new ways to teach the Pythagorean theorem or the War of 1812.

To ensure students are able to learn, Wisconsin teachers have realized they must work to improve their students' mental health and change their classrooms and their methods to respond to new behavioral challenges.

It's a major balancing act, said Linda Hall, director of the Wisconsin Office of Children's Mental Health, part of the state health department.

And that pressure feeds into the larger issue.

"In terms of anxiety — and nearly one out of two kids is experiencing anxiety — kids are saying it's academic stuff that they're anxious about," Hall said. "There's a real need to create some space to actually deal with the emotions and the trauma that kids have been through."

Kids in Crisis: How do Wisconsin educators close the academic gap? Start with student mental health.

Modeling good behavior and establishing trust come first

Young people have always groaned and panicked over academics, but Hall said it's only one part of what keeps this generation up at night. Research shows that climate change, gun violence and political divisiveness are top concerns for today's youth, a three-headed monster unique to this generation.

That's a challenge for today's K-12 teachers. If they're to build trust and get through to young people, they have to teach with compassion and rise above the rhetoric kids see on social media and hear around the dinner table, Hall said.

For Rice, it was clear that he had to form relationships with his students to better understand their struggles, so he started checking in with them, asking questions like "How are you doing?" "What are you going through?" and "What do you need so I can support you?"

Through those questions, Rice has been able to get a sense of what is affecting his students outside of the classroom. Rice said he recently talked to an exhausted student who told him she didn't go to bed until 1 a.m. because she was on Instagram Live. Other students have had to scramble to get to school when their buses are canceled in the wake of Milwaukee Public Schools' bus driver shortage.

"Being that one trusted adult can make such a difference, and there's research that backs that," said Andréa Donegan, a school counseling consultant with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. "That's something we can all do, no matter what type of staff member we are."

Wisconsin educators learn 'mental health first aid' to reach students

For staff at the Kettle Moraine School District in Waukesha County, training in mental health first aid has been critical. Justin Bestor, the principal of Kettle Moraine High School, said when they first start at the high school level in classrooms, teachers have "zero part of any training" in mental health awareness — aside from letting students know they can seek out the school counselor.

If a student consistently shows up late to school, it isn't always clear whether that tendency is the result of a mental health challenge or a "sleepy teenager," Bestor said. Knowing what symptoms of depression look like can shift the playing field.

Kids in Crisis: More schools are training their staff in mental health first aid. Here's how it works.

Teachers may have even better insights into a young person's behavior than their parents, said Rebecca Ladsten, director of Kettle Moraine High School of Health Sciences and math teacher, since they're able to see these students interact and engage more during daytime hours.

"(Mental health first aid) is about observing changes in a student’s behavior and initiating a private conversation, connecting students with the counseling department, communicating with parents," Ladsten said.

Not all signs are as clear as a teenager's persistent tardiness, especially if they're still learning how to form sentences and write.

Younger children may not have climate change, gun violence, political divisiveness or even academic performance weighing on their minds, but their attention spans and stamina have certainly suffered, said Abbey Morris, a K-5 teacher at Goodrich Elementary School in Milwaukee.

Morris described remote learning as a gradual descent from something fun and new to something boring and isolating.

“The kids were just sad; they would say, 'When can we come back? We miss you,'” Morris said. The next fall, she had to do a first day of school virtually for second-graders. “It was me being IT for four hours.”

Missy Schmeling, executive director of Encompass Early Education and Care, noticed similar struggles. The Brown County-based child care centers had previously functioned as after-school venues, a place for children to play with friends. During the pandemic, school-age children were spending full days at the center. Instead of play-based learning, they had to hunker down in front of devices for remote learning.

It has led to younger students preferring to work alone instead of collaborating and sharing with others, a social-emotional milestone in early brain development.

RELATED: Wisconsin preschoolers are 5 times more likely to be expelled than K-12 students, but why?

Teachers make time and space for students to share emotions, encouragement

Latoya Friend's students returned from remote learning struggling with how to communicate their emotions. Friend, who worked as a middle school science teacher at Milwaukee College Prep for seven years, described students toggling from frustration to being overwhelmed to anger in swift succession, taking it out on one another and on her.

Friend shared concerns that schools may focus on closing academic gaps, without leaving enough time for working through the social-emotional issues kids are facing. She incorporated a reflection period at the start of class to help kids express their emotions through writing, drawing and meditation.

Libby Strunz, a school mental health consultant for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, described a "mindset shift" across schools when it comes to improving mental health. Research, again and again, shows that mentally healthy students experience better academic outcomes, which is why DPI has introduced programs to train teachers on best practices, and made social-emotional learning — a tool that helps children manage their emotions and navigate social interactions — part of the curriculum.

In Green Bay schools, students of all ages sit in a circle and engage in conversation-based games like "Would you rather ... ?" The stakes range from low (Would you rather be a kangaroo or a koala, and why?) to high (Would you rather face challenges alone or as a community, and why?).

The exercise — part of an approach called Culturally Responsive Minds — centers students and gets them to build up their community, said Christina Gingle, the district's associate director of pupil services.

"Once you have community-building established, it's going to be a lot easier to start to employ your social-emotional learning, where you're talking more about different topics that might be a little bit more sensitive," Gingle said.

Two other prominent programs used in Wisconsin pertain to peer-based suicide prevention, Gingle said. The Hope Squad, often used in middle schools, offers classes that build suicide-prevention skills. Sources of Strength, used in high schools, connects students with community resources.

Morris, meanwhile, uses Second Step Curriculum, a social emotional tool that helps kids form friendships, problem solve, ask for help, name feelings, and help others when they're feeling angry or sad.

After she taught a unit about what emotions like anger, frustration and sadness look like, one of Morris' first-grade students put what she learned into practice. When the girl's deskmate would get frustrated, she would soothe and encourage them by saying, "Take some deep breaths. You can do it. It’s OK."

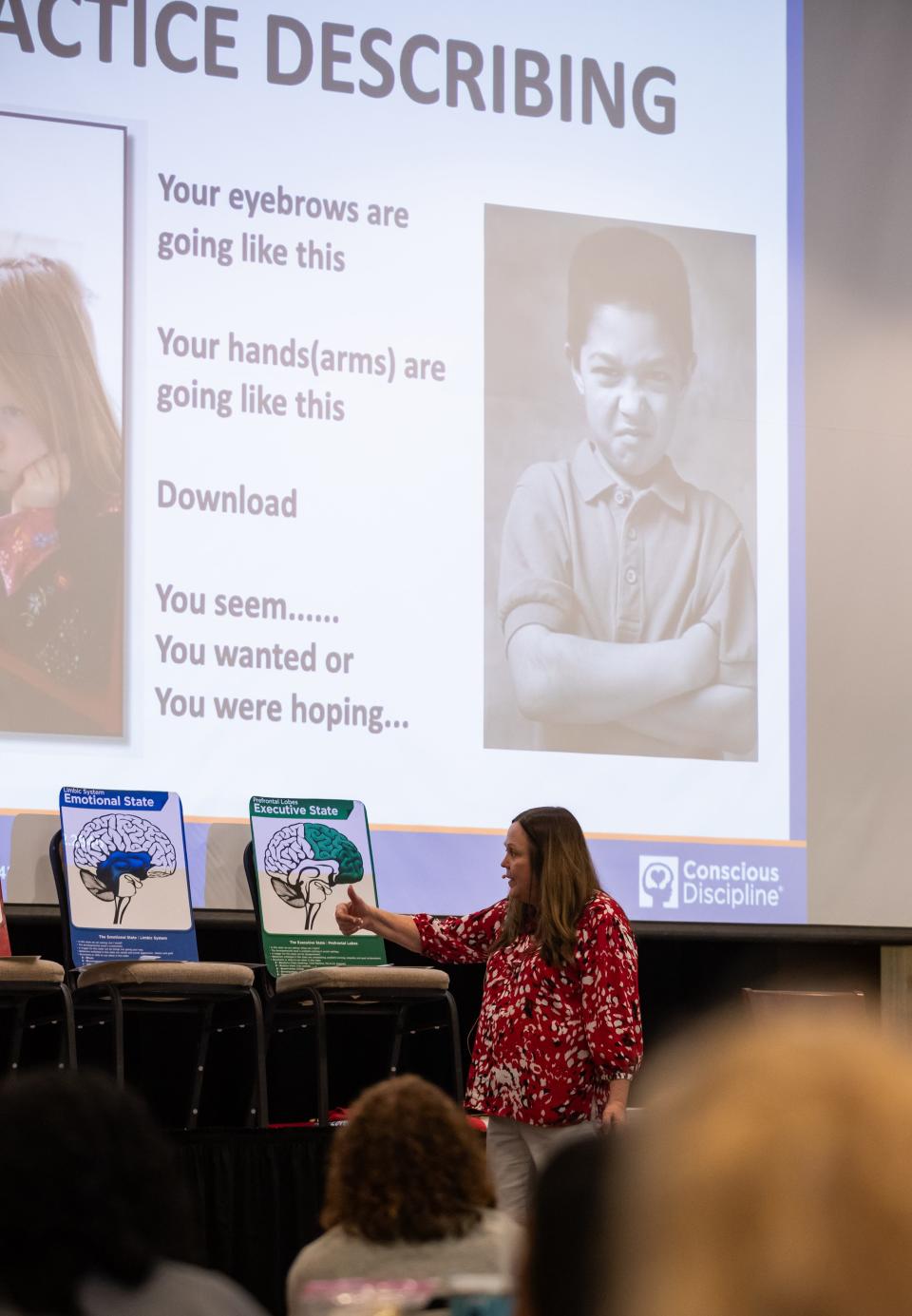

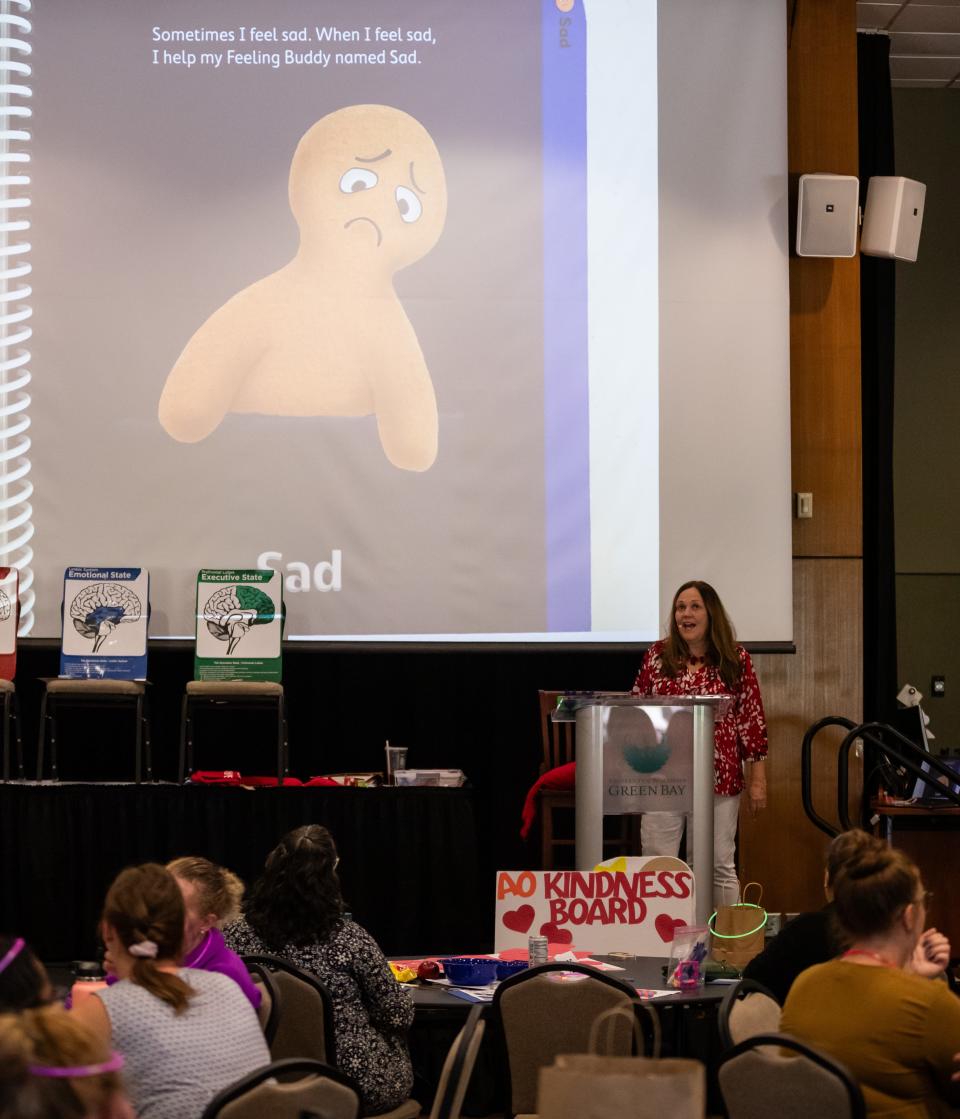

For Wisconsin's littlest ones, a concept called conscious discipline is gaining traction across many early child care centers and has been in practice at Encompass for about 15 years.

Kids in Crisis: What is 'Conscious Discipline,' and how can it help students?

Despite sounding like punishment, it's a social-emotional strategy where the teacher identifies their own heightened emotions and works to get themselves back to calm. The teacher then teaches self-control and -regulation to children.

"We have all kinds of quirky little strategies and songs to help kids self-regulate in the classroom," said Schmeling. "When they are self-regulated … they are ready to learn way more than they would be otherwise.”

Malaika Early Learning Center in Milwaukee uses a strategy called "Malaika Way" that mirrors Positive Behavior Intervention and Strategies, which, among other things, helps young children learn words having to do with self-awareness and self-control, according to executive director and principal Tamara Johnson.

The center also uses Stryv 365, which teaches social-emotional learning through sports — in Malaika's case, tennis.

"There are lessons around calming down, relaxing, focusing," Johnson said.

Today, Rice teaches social studies to sixth-graders at Lincoln Center of the Arts in Milwaukee and has brought with him important lessons from his pandemic days. His students have the option to sit on Pilates balls instead of hard desk chairs when they're feeling anxious. The desks (or balls) are often rearranged into "restorative circles" where students can discuss issues they're faced with that their peers can help them through.

The classroom might break out into a game of bingo, in which students talk to one another to learn if something about them fits the description in one of their squares, like whether two kids in the room are left-handed or love pizza.

Neither classroom bingo nor restorative circles has anything to do with social studies, but to Rice, it's part of a larger plan.

"Students come to me and ask for a restorative circle. And I say 'Yeah, we’ll do that before learning,'" Rice said. "Because if we don’t do that, we won’t have learning.”

Journal Sentinel reporters Rory Linnane, Alec Johnson and Amy Schwabe, Post-Crescent reporters Madison Lammert and AnnMarie Hilton, and Green Bay Press-Gazette reporter Danielle DuClos contributed to this report.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Wisconsin teachers focus on mental health to help students